The EU Suspends Ratification of CAI Investment Agreement with China: Business and Trade Implications

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

The European Commission has said that efforts to ratify the proposed EU-China Comprehensive Investment Agreement (CAI) with China have been suspended after China imposed sanctions on several high-profile members of the European Parliament, three members of national parliaments, two EU committees, and several China-focused European academics.

Those sanctions occurred after the EU had issued sanctions against four Chinese officials and the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau for their alleged involvement in operating education camps in Xinjiang Province.

Although a later anonymous spokesperson for the European Commission denied the reports, saying that the statement made was ‘taken out of context’, EU trade chief Valdis Dombrovskis was quoted as saying: “We have for the moment suspended some efforts to raise political awareness on the part of the Commission because it is clear that in the current situation, with the EU sanctions against China and the Chinese counter-sanctions, including against members of the European Parliament, the environment is not conducive to the ratification of the agreement.”

That doesn’t appear to leave much room for ‘contextual’ interpretations. In this article, we examine why this has occurred, and the implications and precautionary measures that EU businesses should start to consider in terms of the EU Commissions’ relationship with Beijing.

The trade impact

The CAI as an agreement is not a free trade deal; it is a lower form of bilateral investment treaty (BIT) that provides some guarantees of protection for businesses on one side investing in the other. The EU and China had agreed on reducing industrial subsidies, matters relating to the state control of enterprises, and forced technology transfers. Market access was to be improved for EU manufacturers in electric vehicles, telecoms, and private hospitals. Issues of enforcement and arbitration have been at the heart of the talks.

The apparent collapse of the CAI will not have a great impact as China, in any event, has improved market access for foreign investors by recently amending its foreign investment law, reducing the number of restricted markets in its ‘negative list’, introducing a ‘dual circulation strategy’ designed to expand Chinese consumerism, and introduced a variety of regional incentives for foreign investors in areas such as Xinjiang, Hong Kong and the Greater Bay Area, Hainan Island, the Yangtze River Delta, the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, Chongqing, and in specific industries such as finance, AI, healthcare, procurement, and e-commerce. China has also signed up to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Free Trade Agreement giving it market access to all 10 ASEAN nations, including significant markets such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, in addition to markets in Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. The irony is that there has never been a better time to invest in the China market and to sell to Chinese and other Asian consumers.

The significance of the breakdown of the CAI is that the China hawks in Brussels have prevailed against the pro-China business lobby and now have the greater political hand in determining future EU-China policy.

Why did this breakdown occur?

The European Commission was placed under severe pressure from the United States to press sanctions on China concerning two main issues: the political situation in Hong Kong and accusations of ‘genocide’ in Xinjiang.

Hong Kong

The main situation in Hong Kong was the introduction of a bill to permit the extradition of criminals from Hong Kong to mainland China to face trial. That was portrayed in the West as a violation of ‘Hong Kong freedoms’ and a breach of the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ mechanism. It then became a wider call for democratic rights in Hong Kong – which had never previously had them. Civil unrest followed during which the Hong Kong Government passed a series of new laws to prevent rioting and unlawful assembly and introduced new mechanisms to strengthen mainland Chinese rule over the territory. That was again depicted as a breach of the one country, two systems agreement China had agreed with the United Kingdom during the handover of Hong Kong back in 1997. The reality is that Hong Kong has never had democracy, even under British rule, while the 1997 one country, two systems agreement was becoming unfit for purpose after nearly a quarter of a century. China’s attempts to alter it was portrayed as a ‘breach of democracy’ that Hong Kong never had in the first place.

What Beijing has done, however, is to reposition Hong Kong as a wealth management hub servicing mainland China’s estimated US$3 trillion of private wealth. According to the Hurun Global Rich List 2021, Greater China houses the most billionaires worldwide. That means Hong Kong has a significant role to play in introducing international wealth management schemes to mainland China. Companies operating in the financial services industry should be looking at these opportunities.

Xinjiang

The situation in Xinjiang is more complicated to assess, however, and is linked again to the United States. The US has had a military presence in Afghanistan for 20 years, fighting Muslim insurgents and Islamic radicals, including groups such as ISIL and the Taliban, who are also operational in parts of Pakistan. China’s Xinjiang Province has a border with both, and a population of about 13 million Sunni Muslims (Uyghurs) – the same sect as the Taliban.

The US military and NATO troops are set to depart Afghanistan on September 11 this year, believing that there is now ‘no threat’ to the United States from the region. However, no one in the West has openly discussed the impact of the US/NATO withdrawal on China.

Xinjiang has a population of about 13 million Uyghurs and is intensely worried about the potential of radical Islam. In this regard, it has rounded up the more vulnerable and radical influentials and positioned them in ‘re-education centers. That is not ideal; however, it is not ideal for China either. But Beijing is caught between a rock and a hard place here – it either makes moves to secure a region long known to possess radical tendencies – or do nothing and see the violence of the type that has marred Afghanistan and Pakistan; just last week, a bomb exploded in a hotel in Pakistan’s Peshawar where the Chinese ambassador was staying. Beijing wishes to secure Xinjiang and its population from radical Islam. To date, apart from placing those at risk in internment, no one else has arrived at a better solution. At present, there is no violence, no bombs are going off, the mass civilian population of Xinjiang is safe, and no one is being killed.

The EU Commission, however, infuriated Beijing by placing sanctions on Chinese officials involved in running the Xinjiang camps and accused China of ‘genocide’ against China’s Sunni Muslims.

I have traveled extensively throughout Xinjiang for many years. While most of China’s Muslims are peaceful, some of them are extremely conservative – even medieval in their thinking. Young Muslim girls are made to wear purdah as soon as they menstruate, and no longer allowed to socialize. Uyghurs are only permitted to marry other Uyghurs. Mosques are only open to Muslims. The learning of Mandarin Chinese is actively discouraged. The irony is that despite the EU Commission inflicting sanctions on Beijing because of the treatment of the Uyghurs, China’s Uyghur Muslims absolutely do not believe in Western values either. They do not care about the EU. They only care about upholding their religious-cultural values, and as the EU well knows, these can easily become radicalized within Muslim communities. Taking the EU Commissions’ position to a logical conclusion, the ultimate end would be China’s Xinjiang Province run by Uyghurs. I can assure the EU Commission that if that happened, you really would see genocide.

The Xinjiang position exists to deflect attention away from the problems created by the US military and US activities over the past 20 years in Afghanistan. Pointing the finger at China for securing its own territory while accusing it of genocide is pretty rich; whoever signed off on that is grossly unaware of the regional realities while choosing to ignore the 20 years of US and NATO military activity in this part of Central Asia.

What happens next?

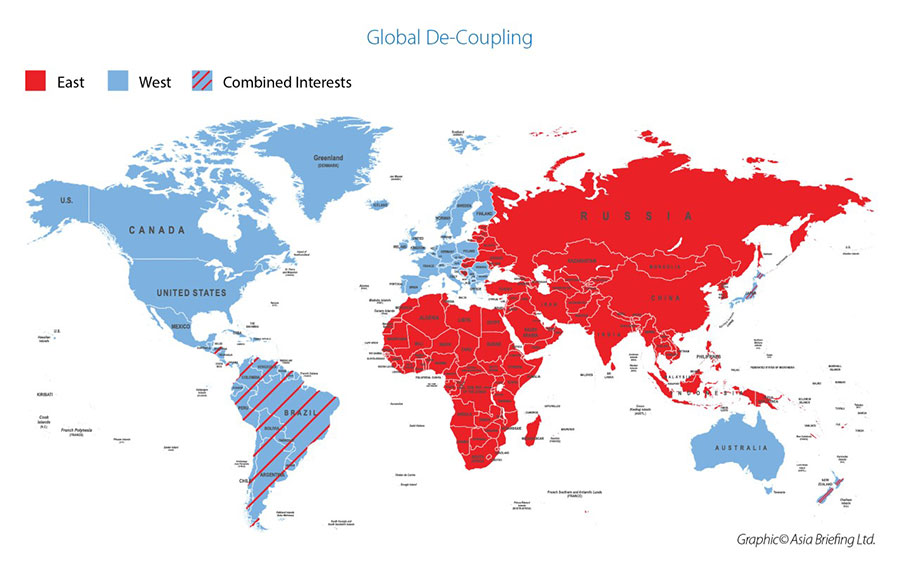

It seems likely that given the position the EU has placed China in, the CAI is effectively dead, and that means the China hawks have taken control of EU policy towards China. That will mean a constant flow of anti-China rhetoric, based upon whatever US state policy is dictated by Washington DC. It also means that the EU is now part of the overall Western push towards ‘decoupling’.

The EU position on the CAI in part brings Brussels back in line with the US own ‘Strategic Competition Act’, which is specifically aimed at China and is designed to counter China’s global influence through a range of political and business protective measures. It is currently in the process of passing through the US Senate. It remains to be seen whether the EU would also create such a bill, though the apparent cancellation of the CAI is indicative.

The political situation in the EU, therefore, is becoming protectionist and discouraging towards EU capital flowing to China. It remains to be seen how far the EU is prepared to go now to legislate to those ends; it appears to wish to dissuade corporates from investing in China. The EU’s political position is overriding those of its own democratic, tax-paying businesses, which ought to be free to spend their money where they see fit. That is a point I made to Joerg Wuttke, the Chairman of the European Chamber of Commerce in China, earlier in the year when he said to me that EU Ministers were putting pressure on Eurocham to speak up about the situation in Xinjiang. My response was that nowhere in the European Chamber’s Articles of Association does it mention having to follow political views, and that if EU Ministers wish to have a voice in the Chamber, then they should join it. The concern is that improperly researched arguments, anti-China politics, and increasing alignment with Washington are now part of EU-China business whether one voted for it or not.

What can businesses do?

While I expect anti-China rhetoric to increase, and the possibility of new EU legislation along the lines of the US Strategic Competition Act to be proposed, EU businesses interested in China in terms of supplying the EU may need to reconsider their China supply chains in the event of any trade war and tariffs being introduced on China products.

Looking at supply chain alternatives

That means looking at regional alternatives, such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, or any of the other ASEAN alternatives. The hyperlinks all lead to articles discussing these.

Strengthening access to the China consumer market

As mentioned earlier, it is now easier than it ever has been to access the China market, which continues to grow and will become the world’s single largest consumer market in both volume and wealth by 2025.

Hong Kong remains a great location for businesses involved in the wealth management sector, while overall, domestic consumption throughout the country continues to rise (including in Xinjiang!).

With China also joining RCEP, opportunities exist to manufacture in China and export to other countries in Asia as well. The future for selling to China remains bright.

Related Reading

An Introduction to Doing Business in Hong Kong 2021

An Introduction to Doing Business in Hong Kong 2021

An Introduction to Doing Business in Hong Kong 2021 is designed to introduce the fundamentals of investing in Hong Kong. Compiled by the professionals at Dezan Shira & Associates, this comprehensive guide is ideal not only for businesses looking to enter the Hong Kong market, but also for companies that already have a presence in the territory and want to keep up-to-date. An Introduction to Doing Business in China 2021

An Introduction to Doing Business in China 2021

Doing Business in China 2021 is designed to introduce the fundamentals of investing in China. Compiled by the professionals at Dezan Shira & Associates in January 2021, this comprehensive guide is ideal not only for businesses looking to enter the Chinese market, but also for companies who already have a presence in the country needing to be aware of the most recent and relevant policies.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article Belt and Road Weekly Investor Intelligence, #27

- Next Article The EU-China CAI Investment Breakdown: What EU Manufacturing Sectors Could Be Hit?