The Greater Bay Area and 2047: Death or New Life for Hong Kong?

Op/Ed by Joseph Percy

In February 2019, the Chinese government released an outline for the economic development of what it coined the Greater Bay Area (GBA), referring to the region encompassing Guangdong province, Hong Kong, and Macau.

The development of the GBA is a priority for the Chinese government in its plan to transition China from a manufacturer of low-end goods to high-end technology. The recently-released document is significant because it begins to detail the roles Hong Kong and Macau might play in this plan.

Hong Kong and Macau were previously Western colonies, both of which were returned to China in the 1990s. The territories were returned on the condition they could continue to exercise autonomy over their political and economic systems for 50 years – an agreement dubbed “one country, two systems”. For Hong Kong, this agreement will end in 2047.

However, many Hongkongers see the GBA as merely a scheme to begin the early integration of their city into the mainland. Others are much more optimistic. The GBA for them is Hong Kong’s economic opportunity of the century. So, who is right?

Economic opportunity or integration scheme? Both.

The government-released plan is titled Outline Development Plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area. Yet, if one reads it, it would quite clearly be more correctly titled Outline Integration Plan.

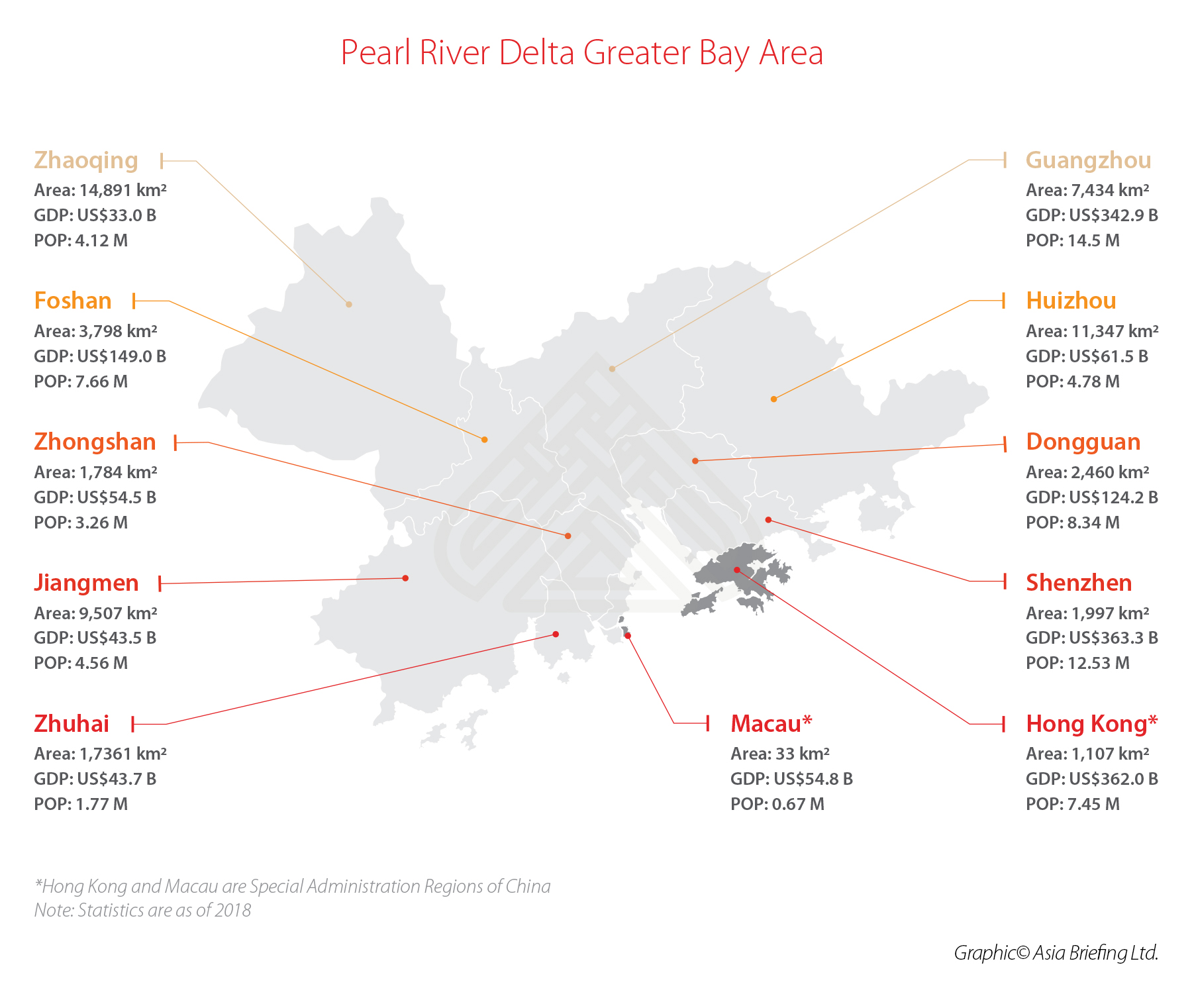

The core purpose of the plan is to build a cooperative framework between Hong Kong, Macau, and Guangdong to facilitate their integration. The GBA has eleven major cities, of which the nine in Guangdong province are the least developed.

If the GBA plan were truly a balanced “development plan”, it seems strange that Guangdong cities are hardly mentioned in their own right. Almost all the plan’s policy ideas relate to Hong Kong or Macau and fit these cities into various kinds of cooperative undertakings with Guangdong.

However, this does not negate the fact that greater cooperation with Guangdong could be economically advantageous.

In 2017, the GDP of the GBA was over US$1.5 trillion, which if it were a country would rank it just ahead of Australia as the world’s 12th largest economy. The GDP per capita of Australia, however, is slightly under 2.5 times that of the GBA’s – a testament to just how much capacity for growth the GBA truly has.

The GBA plan is an economic enticement for Hong Kong and Macau to start building stronger ties with the mainland. And the debate in Hong Kong should reflect this.

Rather than debating if the GBA is merely an integration plan or not, the real question is how to maximize the advantages and minimize the disadvantages of integration.

The kind of integration matters

Not all kinds of integration are made equal. The GBA plan has some policy ideas that have clear economic benefits for Hong Kong. Others are less clear.

The document details a plan to connect all the major GBA cities with a rail system allowing for travel from any city to any other within an hour. While the feasibility of this is not clear, the economic benefits of increased mobility have been shown countless times.

When the plan starts mentioning integrating Hong Kong’s regulatory environment with Guangdong’s, however, the advantages and disadvantages become muddied.

The source of this lack of clarity lies in the utter vagueness of the GBA plan’s policy ideas. The vaguest of these proposals is probably the declaration to “encourage young people to… mingle with each other” – hardly the stuff of concrete policy making.

Few answers are provided in the plan itself, but we can look at the structure of Hong Kong’s economy to assess what the effects of regulatory integration might be.

Regulatory integration needs careful thought

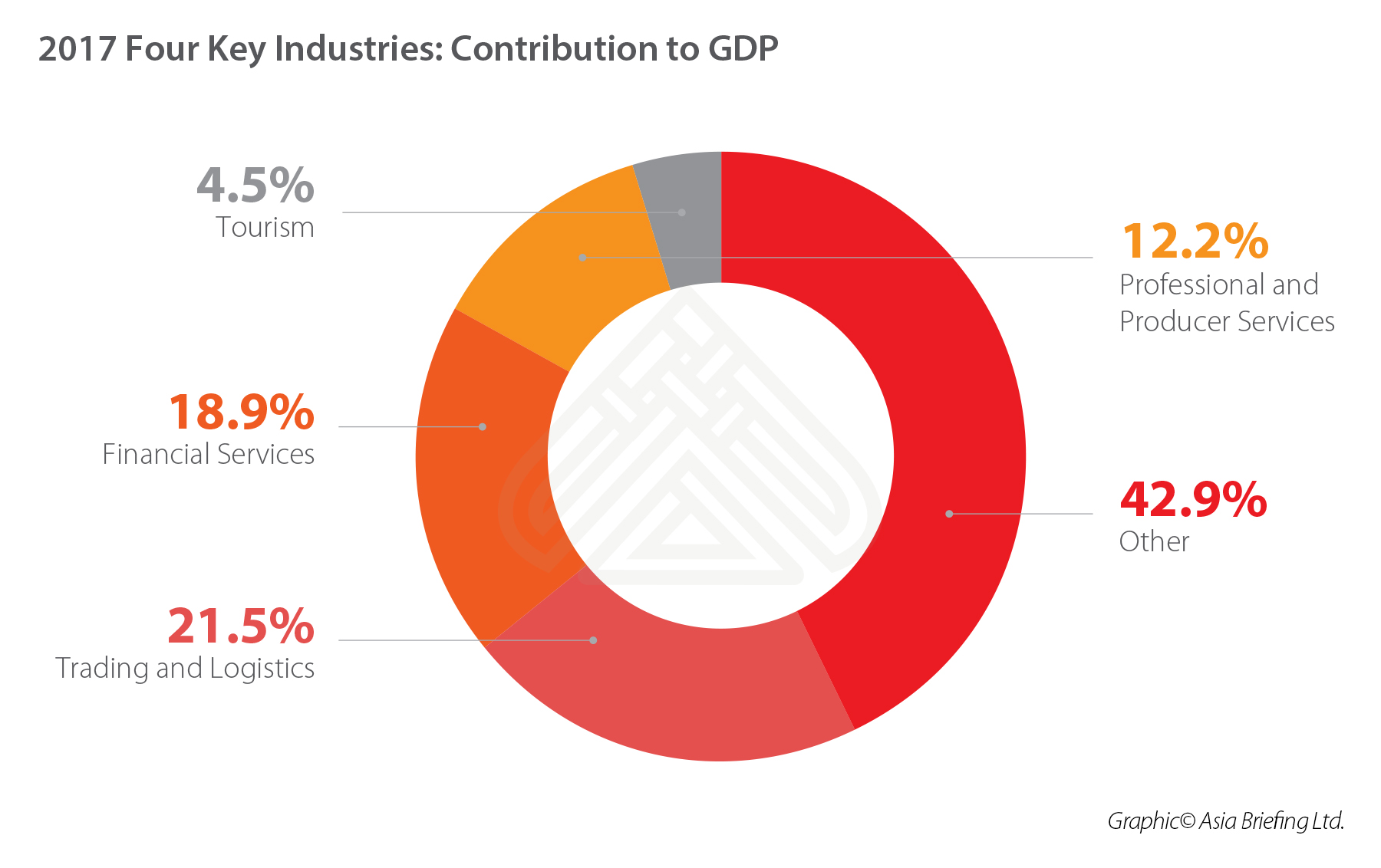

Hong Kong’s economy is heavily reliant on servicing the world’s trade and financing needs.

In 2016, the services sector contributed to 93 percent of GDP. The top three contributing sectors were trading and logistics (21.5 percent), financial services (18.9 percent), and professional and producer services (12.2 percent).

Trading and logistics

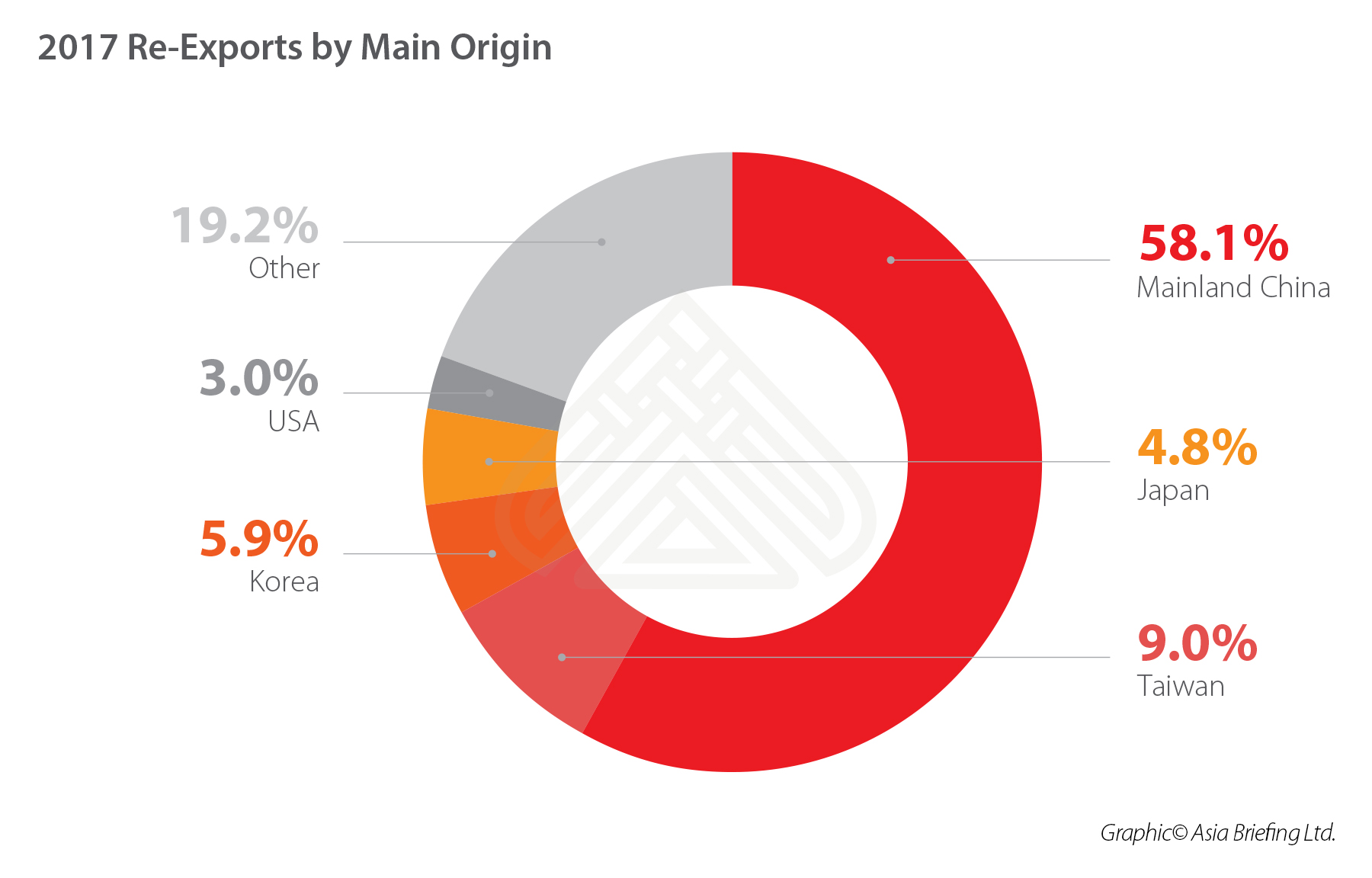

The trading and logistics sector is dominated by the re-exportation and merchanting industries. Both are extremely dependent on the separateness of Hong Kong’s regulatory environment with the mainland’s. As this separateness starts to dissolve, Hong Kong will likely lose some of its competitive edge.

Over 58 percent of re-exports come from mainland China. Currently, Hong Kong is an excellent location for re-exportation because of the low corporate tax rate.

Chinese manufacturers often sell at cost to affiliate companies in Hong Kong, which then re-export the goods to their final destination at a higher price.

The advantage of doing this is that profit is booked in Hong Kong and the manufacturer avoids paying tax at the higher rate set in mainland China.

Hong Kong’s merchanting industry is also dependent on regulatory separateness. Merchanting services are employed by traders to take ownership of in-transit goods to reduce risk.

In Hong Kong, foreign traders enter into contractual agreements with merchanting services rather than with mainland Chinese manufacturers directly because the strength of Hong Kong’s legal system (compared to the mainland’s) gives added security in the case of a dispute.

There are other industries that are reliant on Hong Kong’s separateness as well – for example, Hong Kong’s offshore RBM hub. The truth is, however, that these sectors are at risk not because Hong Kong will increasingly look like Guangdong.

Quite the opposite is true. Guangdong will start to compete with Hong Kong as the province slowly liberalizes, internationalizes, and strengthens the rule of law, just as Hong Kong did in the past.

This means that the regulatory environments of Guangdong and Hong Kong will start to converge regardless of whether Hong Kong actively participates in GBA integration.

However, the continued opening-up and strengthening of institutions in Guangdong is something the Chinese government does want Hong Kong to play a part in.

So, with the knowledge that some regulatory convergence is unavoidable, participating in the GBA could be an opportunity for Hong Kong to help shape the region into one that supports its own economic future.

Finance and professional services

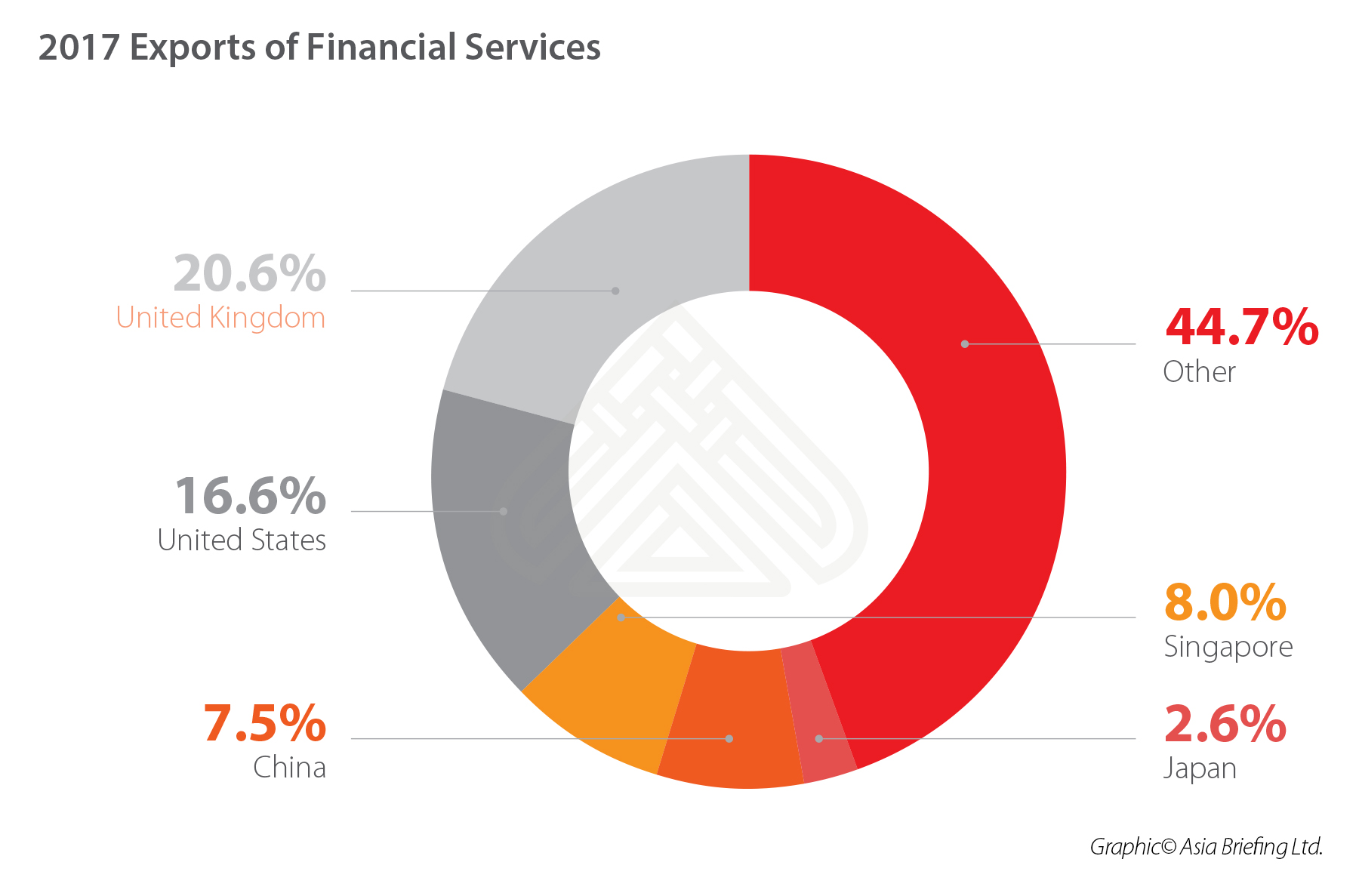

One such space it could do so is in the financial and professional services. In these sectors Hong Kong could benefit from integration with Guangdong by gaining greater access to the mainland Chinese market.

Hong Kong only exports 7.5 percent of all its financial services to mainland China – almost a third of what it exports to the United Kingdom. This is significantly lower than it could be considering Hong Kong’s ties and proximity to the mainland.

Mainland China runs a closed capital account which, in part, restricts the movement of capital between the two regions. Because of such regulations, Hong Kong is unable to fully leverage its financial expertise in the mainland despite its proximity.

For all professional services, Hong Kong firms operating in the mainland only receive the same regulatory treatment as mainland firms in 62 of 153 sectors. This means that Hong Kong loses out to domestic firms and runs a deficit of HKD 11.5 billion (US$ 1.5 billion) with China on the trade of professional services (excluding finance).

Hong Kong’s economy is geared towards exporting such services. The city manages a surplus of HKD 28.5 billion (US$3.6 billion) with all foreign regions (excluding China) combined. If Hong Kong can integrate in a way that gives its firms the same treatment as mainland firms, Hong Kong could export its services to the mainland in the same amounts it does to the rest of the world.

Regulatory integration in the GBA will be difficult – there are three different currencies and three separate legal, tax, and customs systems. Guangdong is also relatively protectionist in comparison to Hong Kong, which is the world’s freest economy.

When working out how these regulatory systems can be integrated, Hong Kong’s government needs to make sure that this does not come with concessions that reduce its ability to export financial and professional services to countries outside China.

Integrating in a way that retains this ability while unlocking the Chinese market would be extremely advantageous. It would likely even spur more business with foreign firms as they use Hong Kong as a conduit for greater access to the Chinese market.

However, the development of the GBA and the regulatory convergence between Hong Kong and Guangdong does mean that industries like the re-export and merchanting sectors in Hong Kong will face increased competition.

Hong Kong needs to preserve the competitiveness of such industries where it can, while using integration and greater access to the mainland market to find new opportunities to replace them as they fade in importance.

Towards 2047 – from death comes new life

In 28 years’ time, the period of “one country, two systems” will come to an end. When it does, much of Hong Kong’s autonomy will be taken away.

Exactly what this will look like is difficult to predict. The Chinese government has claimed it is too early to start discussions on 2047 specifics.

However, in the context of the GBA, Beijing’s ultimate goal is to facilitate the smooth integration of Hong Kong back into the mainland once 2047 arrives. Hong Kong’s goal is to be economically prosperous, but it would also like to be politically autonomous.

The city’s economic prosperity will be shaped by what integration looks like. Regulatory convergence will hurt industries like the re-export and merchanting sectors. But if Hong Kong can preserve the openness that attracts international business while unlocking the Chinese market, integration can work in its favor.

Once Hong Kong’s autonomy is lost, in areas where further integration will clash with the success of industries like the re-export sector, there is no guarantee that Beijing will put the success of these industries over turning Hong Kong into a mainland city.

However, if integration is done in the right way, Hong Kong can secure economic prosperity before its autonomy is lost, and China can secure a smoother transition from two systems to one in 2047.

Even before the notion of the GBA was popularized, in 2017, the BBC published statements by Hongkongers who claimed that mainland China’s influence meant Hong Kong was “already dead”.

Hong Kong’s autonomy will certainly die in 2047, but with preparation it can secure a new economic life for itself ahead of time.

In the words of Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s famous safe-made billionaire: “If you think, then you will be prepared. If you are prepared, then you will have no worries.” Hong Kong’s approach to the GBA and 2047 should be no exception.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia from offices across the world, including in Dalian, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Readers may write to china@dezshira.com for more support on doing business in China.

- Previous Article Human Resources and Payroll in China 2019-2020 – New Publication from China Briefing

- Next Article Pechino e Shanghai rimuovono la richiesta di permesso per l’apertura di un conto bancario societario