Shifts in China’s Industrial Supply Chain and the US-China Trade War

The US-China trade war is forcing companies to shift their supply chain activities out of China, especially at the stages of final product assembly and finishing. Faced with the threat of high tariffs, those selling to the US are deliberating on the most cost-effective strategy.

In key industries, the trade war has triggered major debates among multinational companies on how best to manage their exposure to new costs and ensure unfettered access to American consumers. Companies are asking whether they need to diversify their sourcing strategies or move out of China entirely.

Yet, these concerns are not new ones.

As China continues to experience a slowdown alongside rising costs of doing business and tightening regulation, the timeline of these board-level decisions is simply speeding up.

In this article, we spotlight two major industries – the electronics and textile and apparel – to assess what shifts have taken place in their supply chain ecosystem, what are their triggers, and the new opportunities and challenges that firms need to prepare for.

But first we ask a basic question.

Will foreign companies move out of China?

Most companies cannot afford to consider a wholesale relocation of their factories out of China or replace their Chinese sourcing vendors. This is because supply chain infrastructure takes time to establish and China is at the heart of most of the world’s production, sourcing, and procurement needs.

However, for many firms, the benefits of shifting manufacturing out of China or diversifying production channels may be greater in the longer term given China’s steadily rising labor costs, mounting compliances, social insurance commitments, stringent environmental checks, and other pressures.

These concerns also disproportionately impact those at the lower end of the manufacturing process, many of whom have already shifted to lower cost destinations.

For example, the American business-to-business manufacturing platform Sourcify moved its factories to India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Philippines, and Mexico as labor costs rose in China.

Most apparel makers who depend on a lot of cut-stitch-and-sew labor have moved production out of China, although they maintain some presence in the country such as a front office or headquarter. Within China, apparel is increasingly produced by robotics used in assembly lines.

Advantage ASEAN

For years, business analysts have been writing up the advantages of firms diversifying their production strategy. This means reducing overreliance on one production center and supporting it with a second or more regional base(s), either geographically close or easily accessible.

Here, the US-China trade war’s biggest winners yet may be countries within Southeast Asia. Increasingly, firms caught in the trade war’s crosshairs have started identifying select countries in the neighboring region to supplement their China-heavy presence.

The fact that these countries have a favorable trading partnership with China under the fold of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is an added advantage.

Relocating part of the supply chain or opening new plants within any of these countries would allow firms trading with the US to manage their ‘origin of supply’, while maintaining their relationships with other markets, based out of China, more or less.

It still means that manufacturing jobs are not returning to the US, but will be moving out of China – at an incremental pace and motivated by multiple factors.

What do the supply chain shifts look like?

It is undeniable that doing business in China is getting costlier. Yet, how these factors affect a firm’s decision to continue in China or relocate depends on its size, target market, and stage of production.

For a firm that produces apparel or electronic products that require labor-intensive work, it makes sense to explore alternate destinations like Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, and India.

Here, key considerations are: the costs of relocation, access to suppliers, labor market (size, wages, skill development), supporting industries, logistics and infrastructure, and the tax and regulatory regime.

For larger firms that depend on high-tech manufacturing, the decision might not be as simple.

Maxfield Brown, Manager, Business Intelligence Advisory at Dezan Shira & Associates in Vietnam elaborates: “For companies that have yet to move, this is what has held them back. It is next to impossible to beat the level of supply chain integration found in China. In many cases, investors in China have strong relationships with vendors and suppliers that have been built and, more importantly, perfected quality assurance (QA) over decades. Customers are unwilling to accept dips in quality.”

Here we break down supply chain trends in two industries that have traditionally been associated with China’s expansive manufacturing base.

1. Textile and apparel industry

One reason for why the global supply chain in the textiles and apparel industry is centered in Asia, and particularly the Chinese mainland, is the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Textiles and Clothing, which removed all trade quota restrictions on textiles and garments.

After coming into effect January 1, 2005, the agreement allowed China to become a sourcing and manufacturing center, with its abundant labor supply and low production costs proving highly advantageous to multinational firms.

However, over the last five years, major fashion brands and retailers have increasingly chosen to look for sourcing destinations outside of China. Multiple reasons account for this:

- First, China is consistently increasing its minimum wage as it looks to boost domestic consumption – affecting final profit margins.

- Second, the Chinese government is pushing for more automation and less labor-intensive work, which is changing the manufacturing landscape in the sector.

- Finally, the Chinese workforce is aging; combined with other macroeconomic factors like an economic slowdown, it makes sense that firms look beyond China.

However, if we break down how the global textile and apparel industry is presently structured, we see that China continues to dominate both as a supplier of textiles and producer of apparel.

1.1 A buyer’s relationship with China

China’s role in the apparel industry is changing but only gradually and relative to its own domestic industry’s needs and capacity. The country is now exporting less apparel and more textiles. Still, according to the WTO, China tops both segments in global trade.

In 2017, its textile exports amounted to about US$110 billion and apparel exports amounted to US$158.4 billion. And, while China’s market share in world apparel exports fell from a peak of 38.8 percent in 2014 to 34.9 percent in 2017, its world textile exports reached 37.1 percent in 2017 – a new record high for China.

In fact, all countries that are cited as alternative destinations to replace China in terms of sourcing and procurement have a buyer’s relationship with China.

Take Bangladesh, for example. Bangladesh’s readymade garment industry imported 47 percent of its textile imports from China in 2017, up from 39 percent in 2005. The case is the same for all other major apparel exporters from Asia. (See table below.)

- China leads global textile exports

In 2017, China, the European Union (EU), and India were the world’s top three textile exporters – accounting for 66.3 percent of global textile exports, up from 65.9 percent in 2016. They also benefited from faster than expected export growth: China grew by five percent, the EU by 5.8 percent, and India by 5.9 percent.

The US stayed the world’s fourth top textile exporter in 2017, with a share of 4.6 percent, as in 2016.

- China leads global apparel exports

China, the EU, Bangladesh, and Vietnam were the world’s top four exporters in 2017. Together, they accounted for 75.8 percent of the world’s market shares – growing from 74.3 percent a year earlier and a substantial increase from 68.3 percent in 2007.

1.2 Impact of the US-China trade war: China still dominant player

Overall, the US is simply not a major player in the textile and apparel industry’s global supply chain, which is concentrated within Asia and Europe.

It’s why firms doing business with the US cannot afford to consider locating suppliers or building factories in North America – it isn’t feasible, scalable, and will be very costly.

At the most, the ongoing trade war will force companies selling to US markets to diversify their sourcing networks – potentially slowing down China’s exports.

Alternately, this pressure could speed up China’s plans to focus on value-added manufacturing processes and automated factories and shift out lower-end operations.

Even here, firms considering relocating to ASEAN or other low-cost destinations like Bangladesh and India will make their decision based on whether the regulatory uncertainty and infrastructure gaps can be reconciled with lower labor and operation costs.

This is because China’s coastal and inland production bases have set up mature supply chains with well-developed transport and logistics services that are unparalleled when compared to the rest of the world.

For example, Nike depends on Vietnam to produce close to 50 percent of its sneakers and Adidas slightly above 40 percent. Yet, both companies still make most of their clothes in China because of its skilled workforce and efficient infrastructure.

In fact, entire cities in China specialize in manufacturing particular types of clothing.

Yiwu, in Zhejiang province, located 300 kilometers from Shanghai, is informally called the Socks City because of how much it supplies to the world.

In the category of underwear and lingerie manufacturing, China’s export-oriented manufacturers are located in the primary textile productions hubs in Guangdong province (Shantou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan), Fujian province (Quanzhou, Jinjiang), and Zhejiang province (Yiwu).

Nevertheless, the global fashion industry is increasingly adopting a model where the sourcing portfolio is divided between China, Vietnam, and other Asian countries – a move that has accelerated since the US heightened its tariff impositions on China.

2. Electronics industry

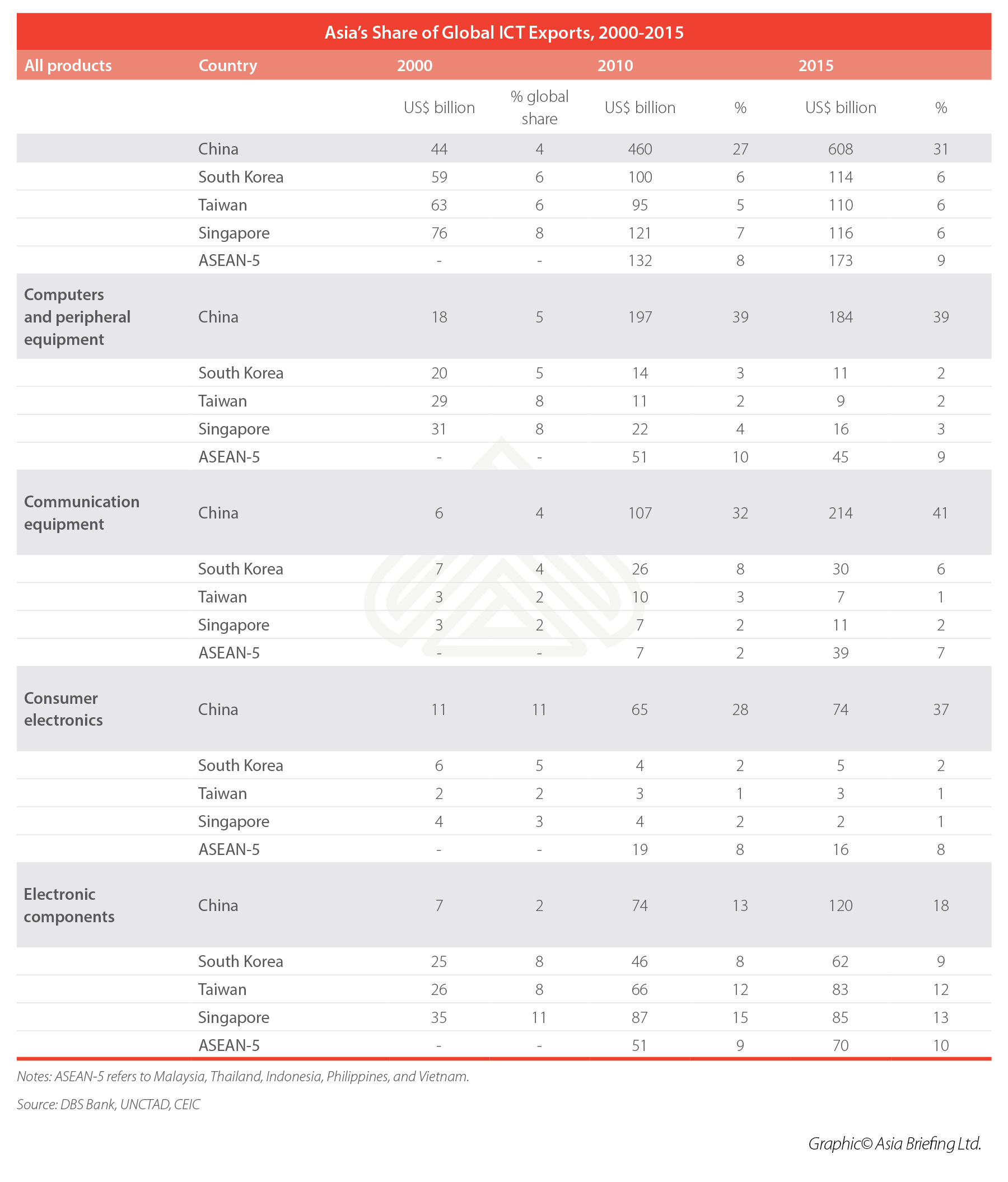

Rapid technological innovation through the development of artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things is creating diverse opportunities within the global electronics industry. This has benefited several economies in Asia as the region hosts the largest electronics industry cluster in the world.

The global electronics supply chain is divided among major production bases in Asia – in China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, ASEAN – for the manufacture of various electronic parts and components, the assembly, testing, and exports of finished products.

A major contributing factor to this regional growth is the WTO’s Information Technology Agreement, which waives import tariffs on IT products and many electronic components among its participating member states.

In effect since 1996, the agreement has promoted the long-term development of electronics trade in the region, emergence of new industries and supply chain clusters, continuous research and development, and ease of relocation depending on the stage of industrial production and regional capacity.

2.1 Asia’s electronics production cluster

Over the last two decades, China benefited from having the world’s leading electronics producers being located within its neighborhood itself – Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore.

Initially assembling products that were designed and manufactured in Japan and South Korea, China has steadily moved up the supply chain with the infusion of technology and capital. The country now produces a wide range of goods across the entire electronics manufacturing segment.

Besides foreign electronics giants sourcing components from and manufacturing and assembling products in China, the country’s local firms such as Huawei, Lenovo, Haier, Xiaomi, ZTE, TCL, Changhong, and Hisense now rank among China’s top 100 electronics and technology enterprises.

Today, China holds more than half of the world’s manufacturing capacity for electronics. More than half of the world’s mobile phones and almost all of their printed circuit boards (PCBs) are manufactured in China.

Chinese factories also match two-fifths of the world’s semiconductor supplies. To put this in perspective, 357 factories operated by Apple’s top 200 suppliers, are in China; only 63 production facilities are in the US. Foxconn, Apple’s main contract manufacturer, employs 250,000 people in the city of Shenzhen in Guangdong province.

2.2 Impact of the US-China trade war: A look at Guangdong

A look at the emergence of the southern province of Guangdong as an electronics manufacturing and technology hub in China explains why large manufacturers and high-tech investors have been reluctant to relocate operations. In 2016, the province accounted for about one-fifth of China’s entire technology manufacturing capacity, with the presence of over 6,500 high-tech firms.

The reasons are plenty.

For one, firms can source anything from Guangdong’s sprawling markets. The SEG Electronics Market, for example, located in the city of Shenzhen, offers component parts, semi-finished and finished equipment, as well as more sophisticated devices – from electronic chips and circuit boards, to small gadgets and smartphones, to video cameras and headsets, to drones and hoverboards.

These markets essentially serve as sales links to thousands of factories located in more interior areas across the country.

Hosting such an integrated network of supply vendors and production facilities has also allowed Guangdong to nurture an ecosystem of firms and startups.

Firms can prototype new industrial designs and manufacture and scale up the production of almost any kind of electronic device in record time – for both international and local clients.

Further facilitating production is the presence of a wide network of venture capital funds, law firms, and corporate services providers in the region, which is well-linked to Hong Kong and major metropolises like Shanghai by high-speed rail and highway.

Nevertheless, Guangdong’s tech sector has also been hit by the US-China trade war.

Lower-value manufacturing had already begun moving to countries like Vietnam and India as they confronted rising costs but the trade war has exposed new exigencies.

For example, Foxconn recently announced that it had laid off 50,000 seasonal workers in China since October due to slowing iPhone sales and is seriously exploring the possibility of manufacturing smartphones in India.

Cable and connector maker Luxshare is setting up in Vietnam and exploring facilities in India. Wistron, the Taiwanese original design manufacturer, has been calculating the costs of a shift out of China as it factors the US tariff threat to its business.

Aware of these trends, both preceding and as a fallout of the trade war – the provincial government of Guangdong has sought to incentivize foreign investment towards the innovation and high-tech sectors.

In September 2018, the province outlined its Policy Measures for Expanding Opening-up and Using Foreign Investment – a 10-point plan to attract foreign investment by opening market access, offering talent and land-use incentives, financial incentives and cash rewards, tax breaks, supporting R&D, and strengthening intellectual property (IP) protection.

Specifically, the plan allows foreign investors to set up wholly foreign-owned enterprises (WFOEs) to produce special-purpose and new energy vehicles (NEVs), drones, aircraft, and other high-tech industries – where joint ventures were previously required. Guangdong also announced that it would invest over RMB 450 billion (US$65.65 billion) in strategic and emerging industries between 2018 and 2020.

Despite strong support coming from government, the trade war has revealed the limits of some of these plans. Leadership in emerging technology like AI and 5G are frontline issues in US-China tensions, which has started to dampen foreign investment in this sector in China.

Foreign firms are reluctant to bring proprietary technology to China, fearing state-sponsored IP theft. The country’s Made in China 2025 project, now apparently on the back-burner, highlighted the extent of China’s own ambitions.

This led foreign companies and the global business community to repeatedly question the means by which China could achieve the rapid transformation and self-reliance (across all verticals in the technology industry) as outlined in the MIC2025 blueprint.

Governments around the world are now increasingly scrutinizing the import of Chinese-origin electronics and components, putting more limits on the extent to which foreign firms can rely on China to source higher-value technology.

These challenges and concerns continue to dominate the agenda in US-China trade negotiations. How China responds to these concerns will determine if they can secure the confidence of major private sector players.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia from offices across the world, including in Dalian, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Readers may write china@dezshira.com for more support on doing business in China.

- Previous Article Hong Kong Enhances KYC Requirements for Company Service Providers

- Next Article Licensing Regime for Hong Kong Trust or Company Service Providers