China’s Digital Yuan: Development Status and Possible Impact for Businesses

This article was originally posted on December 7, 2020, and last updated on May 12, 2021.

Latest updates

- Alibaba’s online grocery service and food delivery units, including ele.me food delivery system, Tmall supermarket, and Hema grocery stores, are included in China’s digital yuan pilot program, Caixin has reported on May 11, 2021. Users of these platforms may find a “digital yuan” option in their payment options. This allows the sovereign digital currency to access the internet giant’s one billion users.

- China’s digital yuan pilot program now also includes a private bank. Zhejiang E-Commerce Bank, based in Hangzhou of Zhejiang province, became the seventh bank, along with six state-owned banks, in China to offer the testing of digital yuan, according to reporting by national paper, China Daily. The Ant Group, Alibaba’s financial technology arm, has the largest share in the Zhejiang E-Commerce Bank, at 30 percent.

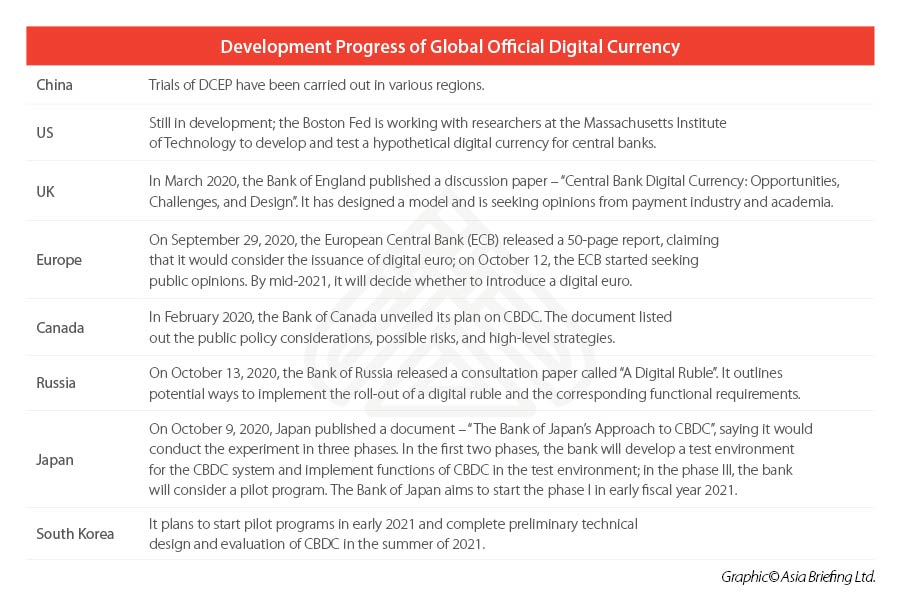

Governments around the world are exploring the viability of digital currency. According to the BIS, 80 percent of the world’s central banks have already started to conceptualize and research the potential of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), 40 percent are building proofs-of-concept (PoC), and 10 percent are deploying pilot projects.

China is at the forefront and is expected to become the first major economy to launch a CBDC. Its sovereign digital currency program, dubbed Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP), has launched one of the largest real-world trials in several cities over the last few months. By May 2020, China had already filed more than 120 patent applications for its official digital currency (alternately referred to as digital yuan in this article), more than any other country.

What is the development status of China’s DCEP?

On-the-ground trials and tests

This April, China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), gave the green light to conduct hypothetical-use tests of the digital yuan in several regions – Beijing-adjacent Xiong’an New Area, Shenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu, and the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games locations.

Another confirmed city is Hong Kong. On December 4, Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) Chief Executive Eddie Yue said that the PBOC and HKMA were preparing to test the use of digital yuan for cross-border payments.

In the latest digital currency trials, Suzhou municipal government announced on December 4 that it would give away 100,000 digital red packets, each containing RMB 200 (US$31) and totaling RMB 20 million (US$3 million), to residents via a lottery. Suzhou has been spearheading the digital currency trails. Since May, some Suzhou government employees have been receiving their transport subsidies in the form of digital currency.

One month ago, a similar trial was run in the southern tech hub of Shenzhen. In October, the city carried out a lottery to give away a total of RMB 10 million (US$1.5 million) worth of the digital yuan. Nearly two million people applied, and 50,000 of them won. The winners downloaded a “digital RMB app”, received the digital yuan debuted with a face value of RMB 200 (US$31), and spent it at over 3,000 merchants in a particular district of Shenzhen.

Other trials are smaller. In April, Xiong’an authorities invited 19 companies, including McDonald’s, Starbucks, and Subway to test DCEP, though the initial result was not exciting – many citizens did not install the payment system.

The pilot city list will continue expanding, and possibly add Shanghai, Changsha, Hainan, Qingdao, Dalian, and Xi’an in the future, according to Caixin, an influential Chinese news agency.

According to a November 2 speech by Yi Gang, the deputy governor of PBOC, more than RMB 2 billion (US$299.07 million) had been spent using digital yuan in four million separate transactions in China. Residents used multiple payment methods, including bar code, facial recognition, and tap-to-go transactions.

Private sector involvement

The private sector is keen to get involved in the DCEP test. The country’s biggest ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing, food delivery giant Meituan Dianping, and streaming platform Bilibili were reported to be joining hands with banks to explore applications of the DCEP.

JD.com, one of China’s biggest e-commerce giants, has become the country’s first virtual platform to officially accept digital yuan, according to the company’s announcement on December 5. The company’s fintech arm JD Digits will accept digital yuan as payment for some products on its online mall, as part of the December digital currency pilot program in Suzhou.

Legal and institutional catch-up

Apart from the test trials, the country’s law is also catching up. On October 23, 2020, the PBOC published the revised draft of the People’s Bank of China Law, laying the legal foundation for sovereign digital currency. The draft law proposed that legitimate currency can be digital currency, giving digital yuan, the same legal status as physical yuan, and any institution or individual must not produce or sell digital tokens to prevent risks associated with virtual currencies.

At the end of October, the Chinese Communist Party’s recommendations on the long-term plan for the economy through 2035 emphasized again to “steadily advancing digital currency research and development.”

Externally, the country is seeking a seat at the global digital-currency table. Over the last few months, Chinese President Xi Jinping has stressed the need for China to get involved in the development of global standards and rules related to digital currencies. In a speech at the G20 summit on November 21, he called for the organizations “to discuss developing the standards and principles for central bank digital currencies with an open and accommodating attitude, and properly handle all types of risks and challenges while pushing collectively for the development of the international monetary system.”

How does China’s DCEP run and what does it look like?

China’s central bank is responsible for issuing and distributing the digital yuan to commercial banks. Commercial banks will then channel the digital money to end users. So far, China’s four major state-run banks – China Construction Bank, Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and Agricultural Bank of China – have started large-scale internal testing of the digital RMB wallet.

In late August, China Construction Bank (CCB) opened a digital RMB wallet service in its official app but quickly disabled it after the feature gained widespread attention – probably by accident. However, the temporary launch offered a glimpse of what a digital RMB wallet could look like.

On the wallet management page of CCB’s official app, the digital RMB wallet would have a wallet ID, a current balance, a balance limit, a single payment limit, a daily cumulative payment limit, an annual cumulative payment, a daily remaining amount, and an annual remaining amount.

The bank’s user agreement detailed that there would be four levels of the digital RMB wallet with varying balance and payment limits. It also revealed that the functions of the digital yuan wallet would include payment, redemption, transfer, and credit card repayment.

Possible impact of digital currency on Chinese society and businesses

China is increasingly transforming into a cashless land – last year, mobile transactions reached RMB 347 trillion (US$49 trillion), accounting for four of every five payments. Amid the technological upheaval in its financial system, the country leads a solo effort on exploring the CBDC, starting as early as 2014.

It’s still hard to predict how soon the DCEP could supersede or complement the payment services provide by Alibaba and Tencent, China’s two tech giants – their digital wallets have over 1 billion users and account for half of in-store payments and nearly three quarters of web sales in China.

However, once successful, this will be touted as a big win for the government as the major economy with the first sovereign digital currency. With such a centralized currency, the government would be able to track all digital cash in circulation, making it much harder for money laundering, tax evasion, and terrorist financing.

According to Xinhua, the state media, China’s DCEP will adopt the principle of “controllable anonymity”. That means, when trading with DCEP, both parties can be anonymous to protect the public’s privacy, but when it comes to combating corruption, money laundering, tax evasion, and terrorist financing, the state banks can still track the trading information.

The central bank could also control the flow direction of the state funds or financial subsidies. For example, if it issues the DCEP to a commercial bank for lending to small businesses, it could ensure that the money is activated only once transferred to a small firm.

Besides, the DCEP can create conditions for unconventional monetary policy. For instance, China might find it easier to make nominal interest rates negative. Normally, when the central bank imposes negative interest rates on bank deposits, residents would withdraw the deposit to avoid capital devaluation. But with the DCEP, negative interest rates could apply to digital cash itself by programming. On the other hand, the central bank could also channel digital cash more directly to residents’ electronic wallets to stimulate the economy.

Internationally, the DCEP may, at some point in the future, help China to be able to transfer digital money across borders without needing to go through a dollar-based international payment system like SWIFT. With the US dollar dominance and its intentions to close the liquidity taps on specific countries or institutions or people, such as via targeted sanctions, China appears to be building its own private trading channels with some countries.

The Chinese government is yet to confirm a proposed timeline for the roll-out of the digital yuan. But it is all but certain that the DCEP will usher in a new financial era in China. Hi-tech businesses as well as foreign-invested retailers, financial institutions, and mobile app developers in China need to watch its progress closely to track how this will impact their scope of business, affect user behavior, and trigger any risk exposure.

This article was originally published on December 2, 2020. It was updated on May 12, 2021 to include latest developments.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

We also maintain offices assisting foreign investors in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, United States, and Italy, in addition to our practices in India and Russia and our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative.

- Previous Article When Can I Buy, Use, and Trade China’s Digital Yuan?

- Next Article What’s Next for Australian Wine in China?