Joining CPTPP: What China Needs to Do and Comparison with the RCEP

We examine China’s bid to join the CPTPP, the challenges it needs to overcome to gain membership, and differences between the RCEP and CPTPP agreements.

China has formally applied to accede to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) trade agreement in September 2021. This comes less than a year after it signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement with the other 14 countries in November 2020.

As mega free trade agreements (FTAs), the CPTPP and RCEP share similarities in aspect of their membership and aspiration. They have seven common members, and both encourage their member states to slash tariffs, offer greater market access, and promote easier trade and investment.

China’s bid to join CPTPP has sparked debates over its chances of success. As we know, the CPTPP, hailed as a high-standard FTA for the 21st century, sets higher entry barriers than the RCEP.

This article explains the CPTPP and its accession process, provides some objective information on the differences between the CPTPP and RCEP, and analyzes the possibilities of China joining CPTPP.

What is CPTPP and how is it different from the RCEP?

The CPTPP revolved from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which had been a key component of former US President Barack Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” strategy. However, in 2017 when Donald Trump succeeded Obama, the US pulled out of the TPP, and the agreement never entered into force.

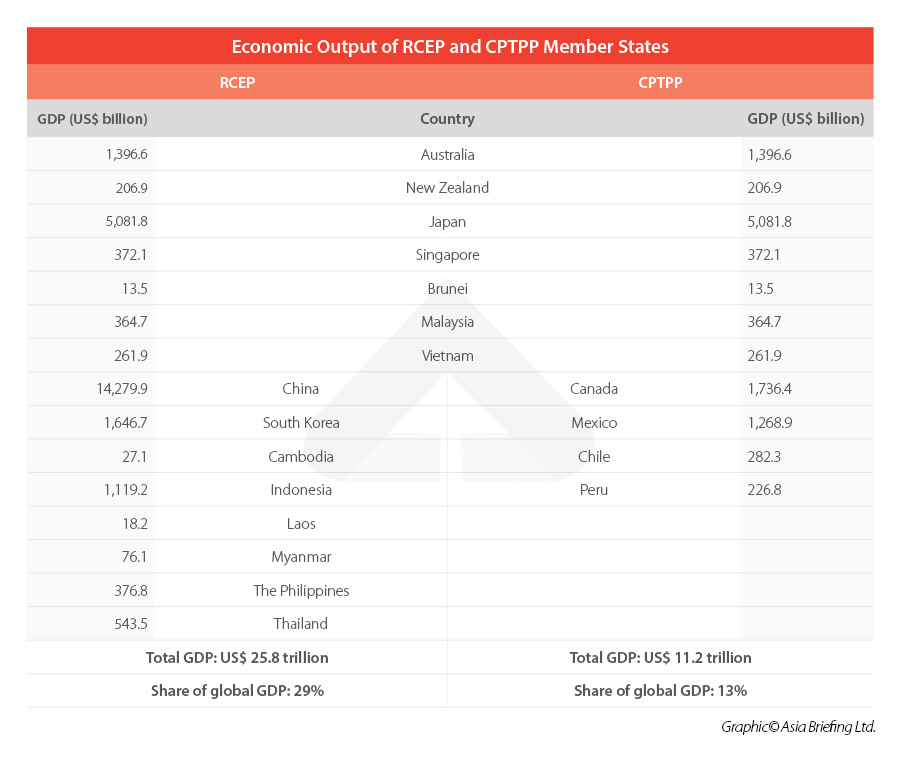

From the ashes of the TPP rose the CPTPP. Led by Japan, in 2018, the CPTPP was signed by 11 countries – including seven RCEP members (Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam), as well as four North, Central, and South American countries (Canada, Mexico, Chile, and Peru). The new CPTPP agreement officially took effect on October 30, 2018.

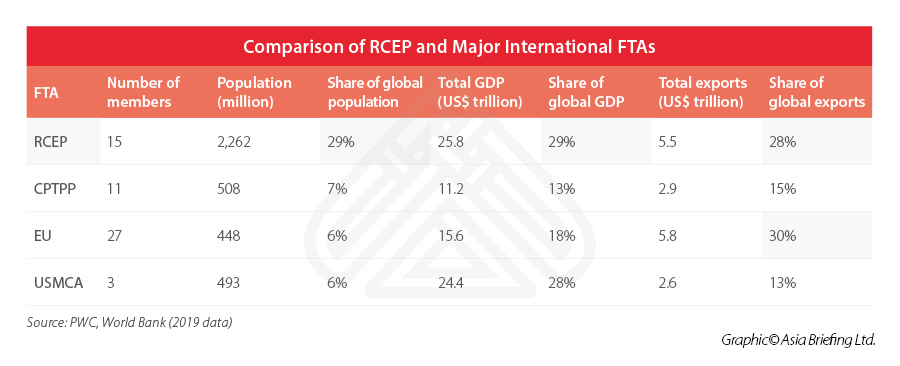

The RCEP agreement signed by 15 countries is expected to come into effect later this year or early 2022. With China’s participation, the RCEP market size is nearly five times greater than that of CPTPP, with almost double its annual trade value and combined GDP, according to Reuters.

However, the CPTPP is widely seen as more comprehensive and deeper than the RCEP.

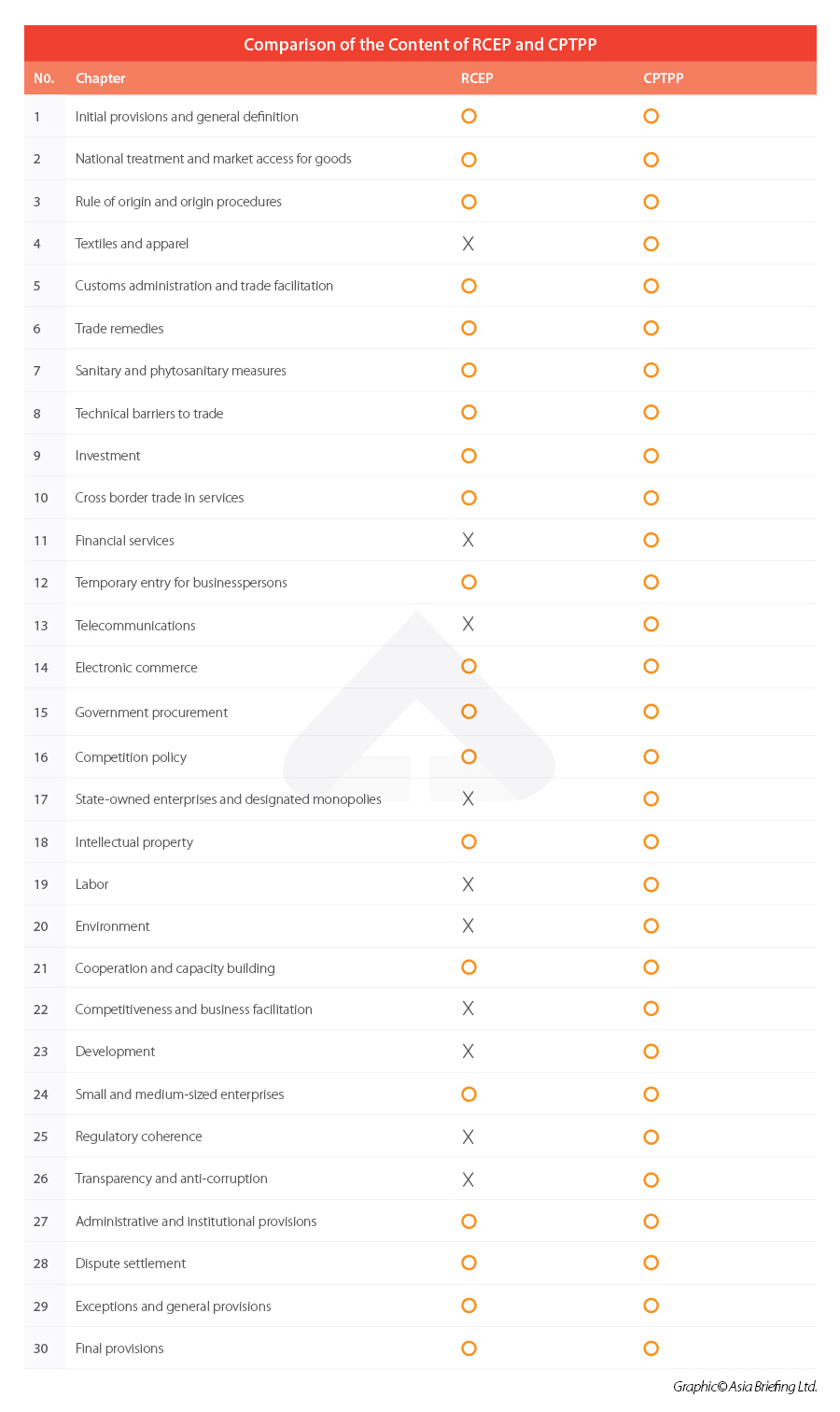

The text of the CPTPP comprises of 30 chapters. It has 10 more separate chapters than the RCEP – including on textiles and apparel, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and designated monopolies, labor, environment, competitiveness and business facilitation, and regulatory coherence. Some of the chapters could task China with compliance homework.

Besides, the CPTPP sets higher standards on economic and trade rules.

To take a few examples, the CPTPP involves greater elimination of tariffs (99 percent) on imports between members, higher than the RCEP (90 percent). Its calculation methods of RVC (regional value content) are more diverse and flexible. It recognizes multifarious types of certificate of origin (CO).

In terms of cross-border trade in services, the CPTPP adopts a unified negative list market access system, while RCEP adopts both positive list and negative list approaches with a lower degree of openness.

The CPTPP imposes higher requirements on intellectual property protection, including in the digital age, as well as transparency in competition law enforcement. And it has a more sophisticated dispute settlement mechanism with a wider scope of application.

The CPTPP and RCEP both have a chapter for e-commerce, but the CPTPP has more requirements. The CPTPP forbids forced disclosure of software source code, explicitly requires non-discriminatory treatment for digital products transmitted electronically, and has regulatory requirements for cross-border data flows by electronic transmission that use personal information (in the course of business activity), among others.

How close China is to joining the CPTPP?

A brief of the CPTPP accession process

It would be hard to imagine China joining the CPTPP in the short term, because the procedure is a long process, and China has so far only completed the first step – applying in a letter to New Zealand’s trade minister on September 16, 2021. (New Zealand is the Depositary of the CPTPP. As Depositary, New Zealand is responsible for various tasks, including receiving and circulating specified notifications and requests made under the Agreement.)

Following China’s application, a commission of representatives from CPTPP member states will determine whether to proceed with the accession process. If the commission agrees, an accession working group (AWG) will be formed.

Then China needs to provide the AWG with plans to meet compliance standards, and submit its offer for terms of market access, including list of domestic measures that do not comply with CPTPP standards.

When all member states of the CPTPP give their assent to China’s offer, a negotiation process between China and the AWG will begin. China may also need to hold talks with other individual members, as considered appropriate. Many experts thus expect the negotiation process to be drawn out.

If negotiations succeed, the commission will ultimately determine, by consensus, whether to approve the terms and conditions for China’s accession to the CPTPP submitted by the AWG.

Of course, China is not the only economy with a pending application. The Taiwanese government lodged an application to join the bloc less than a week after China. The UK is more advanced in the process, having begun accession talks in the summer of 2021 with the 11 CPTPP members.

Opportunities and challenges facing China

To gain the membership of the CPTPP, China mainly has two hurdles to clear – one is to get the consent of all CPTPP members and the other is to meet the high standards of the CPTPP.

Mixed reactions among CPTPP founding members

As we mentioned earlier, China needs to get all 11 signatories’ consent in order to join CPTPP. However, its strained relations with some CPTPP members, notably Australia, Canada, and Japan, may hurt its chances.

Trade frictions between Australia and China have been escalating during the past two years. Diplomatic interactions between China and Canada have not yet warmed after the release of Huawei’s CFO and the “two Michaels”. And Japan, as another Asian powerhouse, is wary of the prospect of China taking a leading role in shaping Asian trade. Aside from these, Mexico has also taken a cautious stance.

On the other hand, CPTPP members in the ASEAN bloc have exhibited little resistance to China’s joining. Malaysia’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry said in September that it “looks forward to welcoming” China’s entry. The Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said during Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to the city-state in September that he welcomed China’s consideration of joining the pact.

According to The Economist, of the CPTPP members, only Canada and Mexico now trade more with the US than with China. The potential economic gains of having China on board are still large for many CPTPP members. The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), a think-tank in Washington DC, published a paper in 2019, which estimated that global income gains from the CPTPP – as it stands – run to US$147 billion a year. If China were included, that would rise to US$632 billion. Many CPTPP members may receive benefits worth more than one percent of their national income with China’s joining.

China’s distance to reaching CPTPP standards

According to Jeff Schott of the PIIE, “China is surprisingly close to meeting CPTPP conditions in many areas. But where there are gaps, they’re huge.”

In fact, China has made huge strides in recent years on market access, business environment, and intelligent property rights. The country routinely shortens the negative list for foreign investment, released the first negative list for cross-border services trade in Hainan Free Trade Port (FTP), and has been cutting red tape, opening its financial sector, and strengthening the protection for trademarks, copyrights, and patents.

However, China still has big difficulties meeting CPTPP rules on the treatment of SOEs, data flows, and labor rights.

The CPTPP does not ban SOEs, but it does try to discipline and restrict certain types of behaviors in the marketplace, particularly by state firms providing commercially competitive goods and services for profit (there are exemptions for local-government SOEs and those delivering unprofitable domestic services).

It may be hard for China to stop subsidies and aid for its domestic SOEs, which it often insists are necessary for providing jobs, managing critical resources, or maintaining and orderly financial system.

Vietnam, as a CPTPP founding member, also has heavy state presence in the economy. It had to agree to restrictions on support for its state firms and to improve the transparency of their operations and structures in order to join the CPTPP.

According to the Brookings, a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington DC, Vietnam was able to receive some exemptions for its SOEs. However, it is not sure whether China can be granted that much room for flexibility given the country’s mammoth state economy.

Data governance is a field where China is moving towards the opposite direction from the spirit of the CPTPP. The CPTPP promotes free cross-border data flows among member states. In contrast, China has tightened data localization requirements under the new Data Security Law, which took effect on September 1, 2021 and will make it harder for foreign companies to move data out of the country.

The CPTPP has chapters for labor and environment, which the RCEP does not have. While China was often accused of forced labor and human right violations in media coverage, according to Hinrich Foundation, given that China and 187 members of the 1998 International Labor Organization (ILO) are signatories to the ILO Declaration, adhering to the CPTPP text should not present an insurmountable challenge.

Environment-wise, China’s recent efforts, include its carbon neutrality pledge, plans to roll out a Yellow River Protection Law, and a more ambitious national action plan on biodiversity conservation, etc.; these moves may make the CPTPP environment chapter less onerous to comply by as well.

In conclusion, China may find its CPTPP application journey arduous, even if it comes within reach of the required compliance standards. Nevertheless, China’s CPTPP bid demonstrates its strong will to promote reform programs and make institutional breakthroughs targeting free global trade.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article Hong Kong Added to EU Watchlist on Non-Cooperative Tax Jurisdictions

- Next Article What is the Kunming Declaration on Biodiversity Conservation and Should Businesses be Interested?