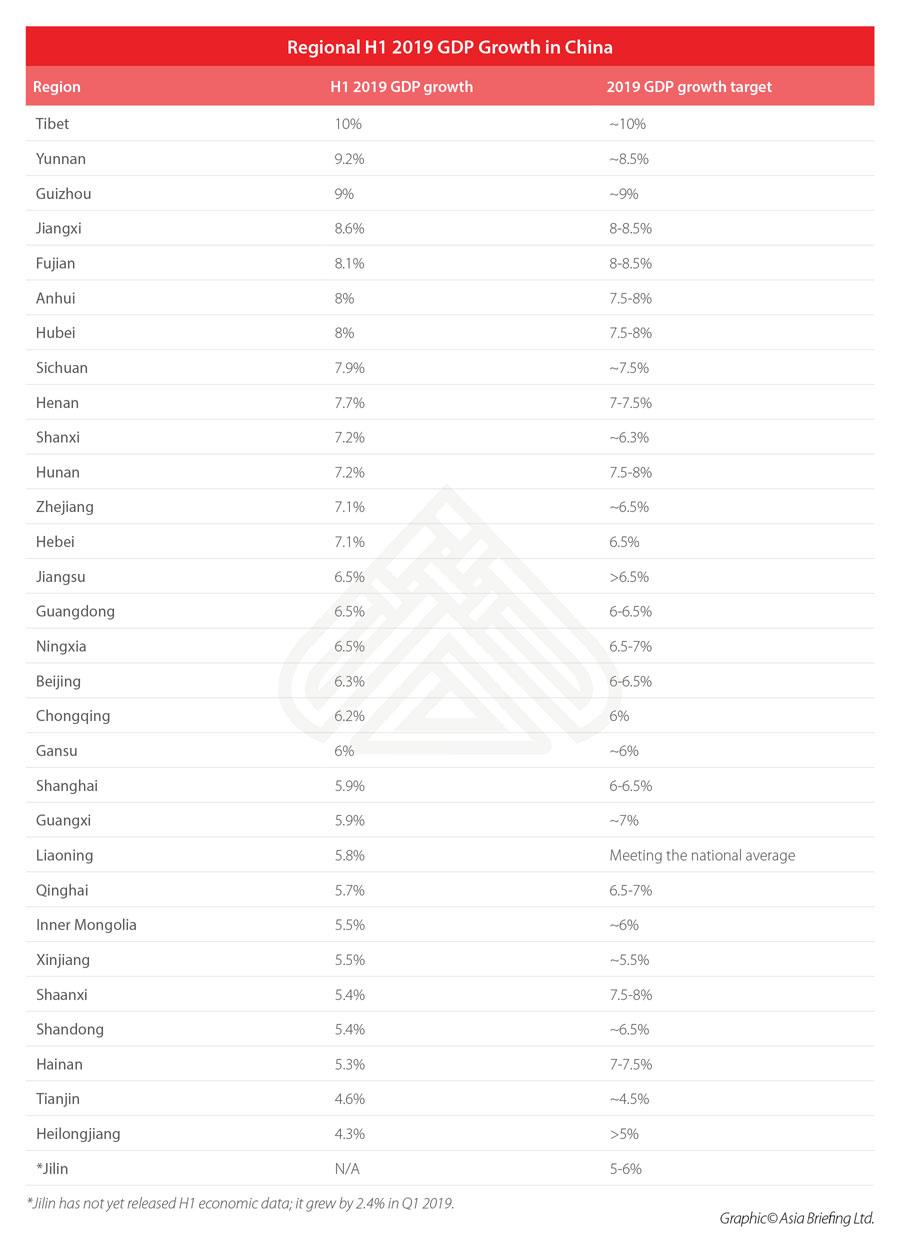

Disparities in China’s Regional Growth: A Look at H1 2019 GDP Data

China’s economy is facing uncertainty not seen since the 2008 global financial crisis.

Domestic pressures are causing a slowdown after years of rapid growth, and the trade war with the US offers an added element of risk. Faced with a mountain of debt, China’s leaders have less room to maneuver than in years past.

Yet, China’s economy managed to chug along at a solid 6.6 percent in 2018 and grew at a 6.3 percent rate through the first half of 2019.

Regional growth trends, however, show that the risks of a slowdown will not be felt evenly across the country.

With rising land and labor costs and a more export-oriented economy, China’s wealthy coastal areas may be more exposed than others to the supply chain disruptions caused by the trade war. At the same time, they are the country’s most diversified and innovative economies, making them best positioned to lead China’s new economy.

Conversely, China’s industrial north is showing no signs of rebounding, despite the government’s best efforts. And while inland regions have seemingly shrugged off the trade war by growing at the fastest rates in the country, questions about their sustainability linger.

As China enters a “new normal” of slower growth, the country is becoming increasingly segmented into distinct regional economies – with some having brighter prospects than others.

Developed coastal regions resilient but showing cracks

Because of the size of manufacturing along China’s east and southeast coast, this region is arguably more vulnerable to trade war friction than others. At the same time, the region is home to the country’s most innovative and advanced cities, which are better placed to withstand trade tensions.

Many US-bound exports from this region are – or will be – hit by tariffs, while many US-origin imports used as manufacturing inputs are subject to China’s retaliatory tariffs. This region is the biggest recipient of FDI in China, leaving it more exposed to the possibility of foreign-invested enterprises relocating abroad in response to trade tensions.

Nevertheless, the east and southeast coast have proven resilient through the first half of 2019.

Fujian, in particular, posted high growth of 8.1 percent, even if this figure falls on the lower end of its 8-8.5 percent growth target. Directly to its north, Zhejiang grew by 7.1 percent to exceed its target of around 6.5 percent.

One of the reasons that these provinces can overcome the uncertainty caused by the trade war is that they have burgeoning service and tech sectors that build off the strength of a well-educated population. Zhejiang, for example, is home to a number of China’s most innovative internet companies, most notably, the e-commerce giant Alibaba.

Still, some areas have shown that they may be exposed to the downward pressures catalyzed by the trade war.

For instance, Guangdong, China’s largest provincial economy, grew by 6.5 percent, putting it on track to meet its full-year target. While on the surface that figure seems stable, some regional trends within the province may be cause for concern.

The high-tech hub of Shenzhen, already one of China’s richest cities, brushed aside trade tensions by growing by 7.4 percent. The provincial capital Guangzhou also produced strong 7.1 percent growth, while the smaller but important cities of Foshan and Dongguan both logged 6.9 percent growth.

In contrast, the city of Zhongshan barely grew at all, registering a shockingly low 0.9 percent rate. Several other small and medium sized cities reported higher but still middling growth, like Jiangmen, which grew by 4 percent.

These diverging fortunes are indicative of challenges facing Guangdong’s economy. On the one hand, its major cities boast highly sophisticated high-tech manufacturing, innovation, and service capabilities – the industries of China’s future.

Yet, the province’s development has led to higher land and labor costs, which, combined with US tariffs, have led many lower-value manufacturers to relocate to inland China or Southeast Asia.

Advanced coastal cities like Shenzhen seem well placed to continue growing unencumbered, but smaller cities reliant on unskilled labor-intensive industries are under pressure.

The diversified economies of the east and southeast coast have managed to withstand a significant slowdown so far, but parts may be beginning to feel the effects of a trade war with no clear end in sight.

North’s struggles continue

Halfway through the year, the struggles of China’s north and northeast coastal regions show no signs of abating.

These struggles have little to do with pressures caused by the trade war. Rather, they are a result of flagging demand for heavy industry, stricter pollution controls, and demographic challenges caused by an aging population and brain drain among the young educated population.

The downturn is most pronounced in the northeastern “rustbelt” economies of Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang. Growing by 5.8 percent, Liaoning is on pace to miss its target of meeting China’s average growth rate, which in the first half of the year was 6.3 percent.

Heilongjiang, meanwhile, reported the lowest growth rate in China at 4.3 percent, below its modest target of greater than 5 percent. Jilin has not yet announced its growth rate for the first half, but in Q1 grew by just 2.4 percent – less than half of the lower range of its 5-6 percent 2019 target.

Government officials have tried to “revitalize” the rustbelt by streamlining the business environment, investing in tech, and offering incentives to attract investment and young talent. These efforts do not seem to have paid off yet, as the region’s traditional industries continue to suffer and brain drain remains a problem.

While the downward pressures are strongest in the rustbelt, other northern regions are experiencing similar issues. Shandong province, for example, grew by 5.4 percent in the first half, which was among the country’s slowest and has put it on pace to miss its growth target by a full point. It is also a full point lower than its 2018 growth rate of 6.4 percent and two points lower than its 2017 growth of 7.4 percent.

Shandong is home to a fair amount of heavy industries – with chemicals, petroleum, machinery, and mineral products among its biggest – but it has a more diversified economy than the rustbelt. Still, its industrial sector grew by just 2.6 percent – slower than even the primary sector, which grew by 3 percent.

Shandong’s exports grew faster than the national average, suggesting that US tariffs were not a significant factor. Rather, Shandong has been hit harder by the lack of domestic demand resulting from slowing construction and infrastructure investment, as well as some industry-specific downturns, like in the auto sector. To boost these sectors, provincial authorities have already announced that they will invest RMB 1 trillion (US$145 billion) to speed up key investment projects, such as airport, railway, and highway construction.

The neighboring city of Tianjin theoretically has room to benefit from proximity to Beijing, but it continued to stagnate through the first half of the year, growing by just 4.6 percent. As with the rustbelt, Tianjin’s struggles predate the trade war; its decline can be more directly attributed to factors such as excessive spending on non-performing investments.

The trends in north and northeast China are clear. Reliance on heavy industry, demographic challenges, and an inefficient bureaucracy are hampering the region.

Structural problems are hurting its economy rather than the trade war with the US, which is mostly impacting it indirectly by dampening domestic and global demand. Beijing, with its advanced service sector and innovative tech industry, is the only truly reliable engine in the region.

The center and southwest – high growth, but is it sustainable?

China’s central and southwestern regions have been the fastest growing in China for years – and 2019 is no exception. Many provinces appear to be brushing off the economic uncertainty hitting much of the country, with some – including Anhui, Hebei, Henan, and Hubei – growing even faster than the year before.

Whether the trends underpinning this growth can be sustained, though, is an open question.

On the plus side, Yunnan (9.2 percent), Guizhou (9 percent), and Jiangxi (8.6 percent) were three of the fastest growing provinces in the first half of 2019, while Anhui (8 percent), Hubei (8 percent), Sichuan (7.9 percent), and Henan (7.7 percent) all showed positive growth.

These regions have benefited from rising costs in China’s coastal economies, as some of the labor-intensive manufacturing there has relocated inland. Some leading provincial capitals like Chengdu and Wuhan have also become dynamic and diversified economies that can compete with major coastal cities in their own right.

Further, policies like the Belt and Road Initiative have improved these regions’ connectivity and opened new international trading routes – which the government hopes will reduce reliance on the US. Yunnan, for example, saw its exports increase by 21.4 percent year-on-year in the first half.

Taking a closer look at the drivers of high growth, however, raises concerns.

As with northern China, the central and southwest’s economic fragility lies with a potentially unsustainable economic model rather than US tariffs. Inland regions are more reliant on fixed asset investment and government-led infrastructure spending than other regions are, as well as land transfers from the central government to local governments, which inflates growth figures to an extent.

Guizhou’s fixed asset investment in the first half of the year, for example, was 12.3 percent – over double the national average of 5.8 percent. Hubei’s was up by 10.8 percent, partly due to infrastructure investment increasing by 16.9 percent.

While high fixed asset investment on its own is not necessarily a bad thing, its utility as a determinant of sustainable growth in inland China is debateable. According to Moody’s Analytics, central and western China’s returns on investments have declined faster than in the east coast, with returns on capital falling by three times from 2010-17 and returns on assets almost halving.

These regions are not in a strong position to continue investment at such high levels as local governments and banks are under pressure to slash debt after enormous stimulus in response to the 2008 global financial crisis.

While the growth rate of western regions has outpaced the national growth rate by 1.8 percentage points since 2012, that is not fast enough to close the gap with the coast as the population grows old. Although costs are cheaper inland than on the coast, the labor pool is already older and more expensive than competitors in Southeast Asia like Vietnam and Indonesia.

Last year, the southwestern megacity of Chongqing provided a cautionary tale for other economies in the region. After years of consistently being among China’s fastest growing regions – including growing by an enormous 17.1 percent in 2010 – Chongqing’s economy suddenly sputtered in 2018, growing by 6 percent and missing its target by 2.5 percentage points.

One of the reasons for its sudden decline was the government’s inability to maintain high levels of fixed asset spending because of its indebtedness and slowing economy. Chongqing has had a more modest level of growth so far this year, increasing by 6.2 percent, in line with a lowered growth target of just 6 percent.

Chongqing’s experience may prove to be a harbinger of things to come for other rapidly growing inland regions.

While they are growing quickly, they are not growing fast enough to converge with the coast or outrun demographic challenges. At the same time, local governments are hamstrung by debt and have to compete with booming Southeast Asian alternatives.

Rise of regional economies

Economic data from the first half of 2019 show that regional disparities in China’s local economies are increasing. These diverging trajectories are primarily due to structural issues in the composition of regional economies rather than exposure to US tariffs and their side effects.

Successful China investors have never treated the country as a single market, keeping in mind the varying levels of development, regional preferences, and different economic compositions that have long existed. Moreover, questions of how to spur the sluggish northeast and develop the west are not new.

But with the country’s economy slowing – and engulfed in a trade war with the US – China’s economic planners are running against the clock to solve these problems. Increasingly, it looks like only certain regions are well-placed to continue high growth in the long-term, while others are at risk of falling behind.

Over the last decade, foreign brands rushed to establish a presence in inland China to capture rapidly growing new markets. As growth slows nationally, however, more opportunities will be found within the high-tech and service-driven coastal economies.

The fruits of economic growth have always been uneven since China first adopted the reform and opening-up policy in the late 1970s. The architect of the program, Deng Xiaoping, acknowledged as much when he declared in 1992, “Let a part of the population get rich first.”

Since then, China has grown richer nationwide, and inland areas have quickly grown to narrow the gap in standard of living with the wealthy coast. But with part of the country getting rich first, part of the country is also maturing economically first – and that means a China with increasingly distinct regional economies.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia from offices across the world, including in Dalian, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Readers may write to china@dezshira.com for more support on doing business in China.

- Previous Article Hong Kong vs Singapore: What’s Next for Foreign Investors in Asia

- Next Article China’s Six New Free Trade Zones: Where Are They Located? (2019 Expansion)