Investment Screening in the EU: Impact on Chinese FDI

Investment screening in the EU has been strengthened through new policy directives that encourage greater scrutiny of investments in sectors considered sensitive.

China Briefing breaks down the screening process and assesses its possible impact on Chinese outbound FDI.

Responding to increased levels of foreign investment in sensitive sectors, in March 2019 the European Parliament Plenary approved a new investment screening framework that will be active over the whole European Union (EU).

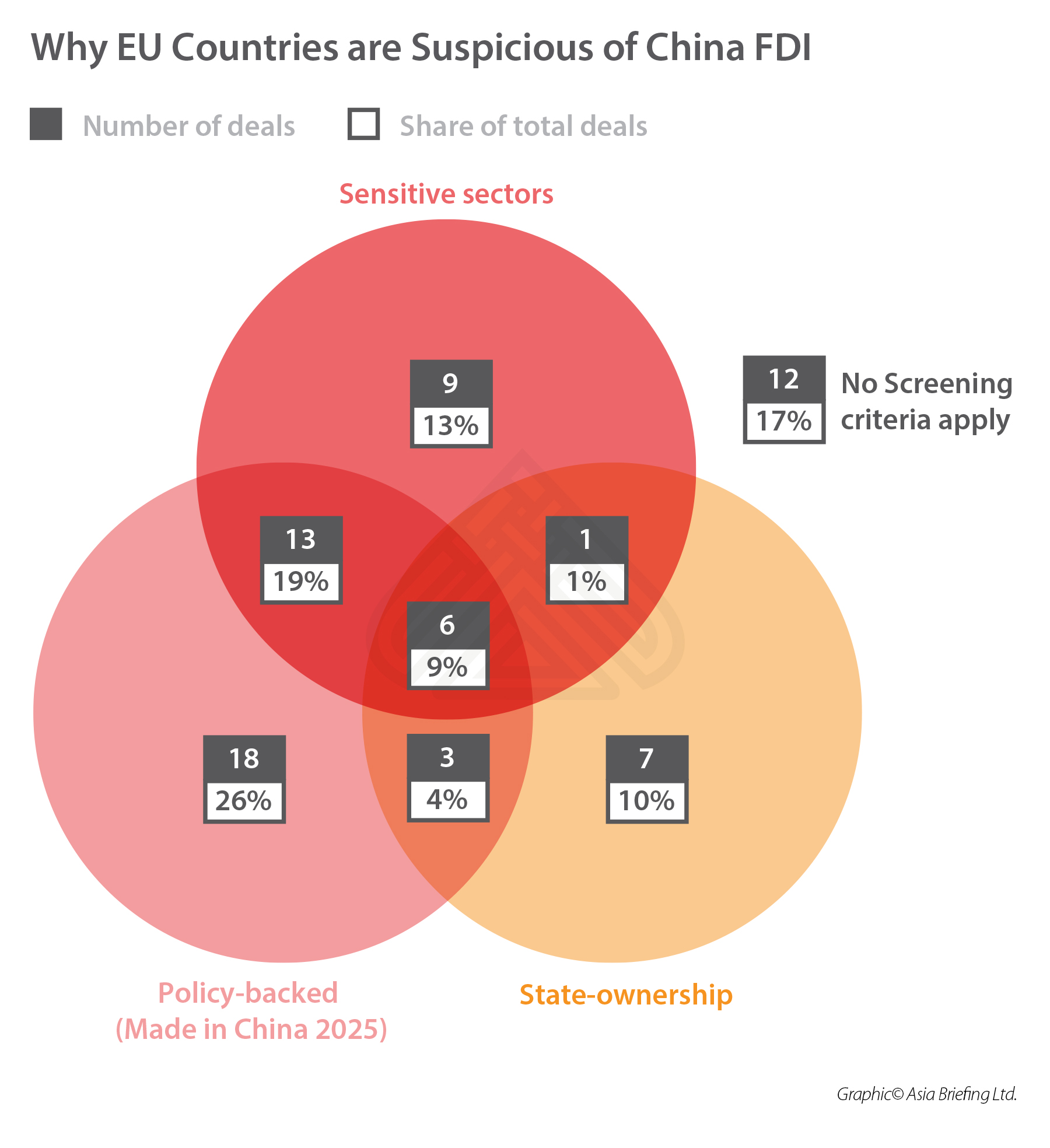

According to the Mercator Institute for China Studies, if the screening framework had been in place in 2018 – as much as 83 percent of all Chinese investment over EUR 1 million (US$1.12 million) could have been investigated under the regime.

The process was started in February 2017 by the German, French, and previous Italian governments, with a letter requesting the European Commission redraw the rules on foreign investment in the EU.

Concerns in the EU that Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) has an underlying political motive were intensified just before the letter was submitted, with 2016 seeing the largest amount of Chinese FDI in the EU ever – 17 times the amount received in 2010.

In this article, we analyze how the new screening policy works, what kind of investments will likely be screened, and the effect it will have on Chinese FDI in the EU.

Investment screening in the EU

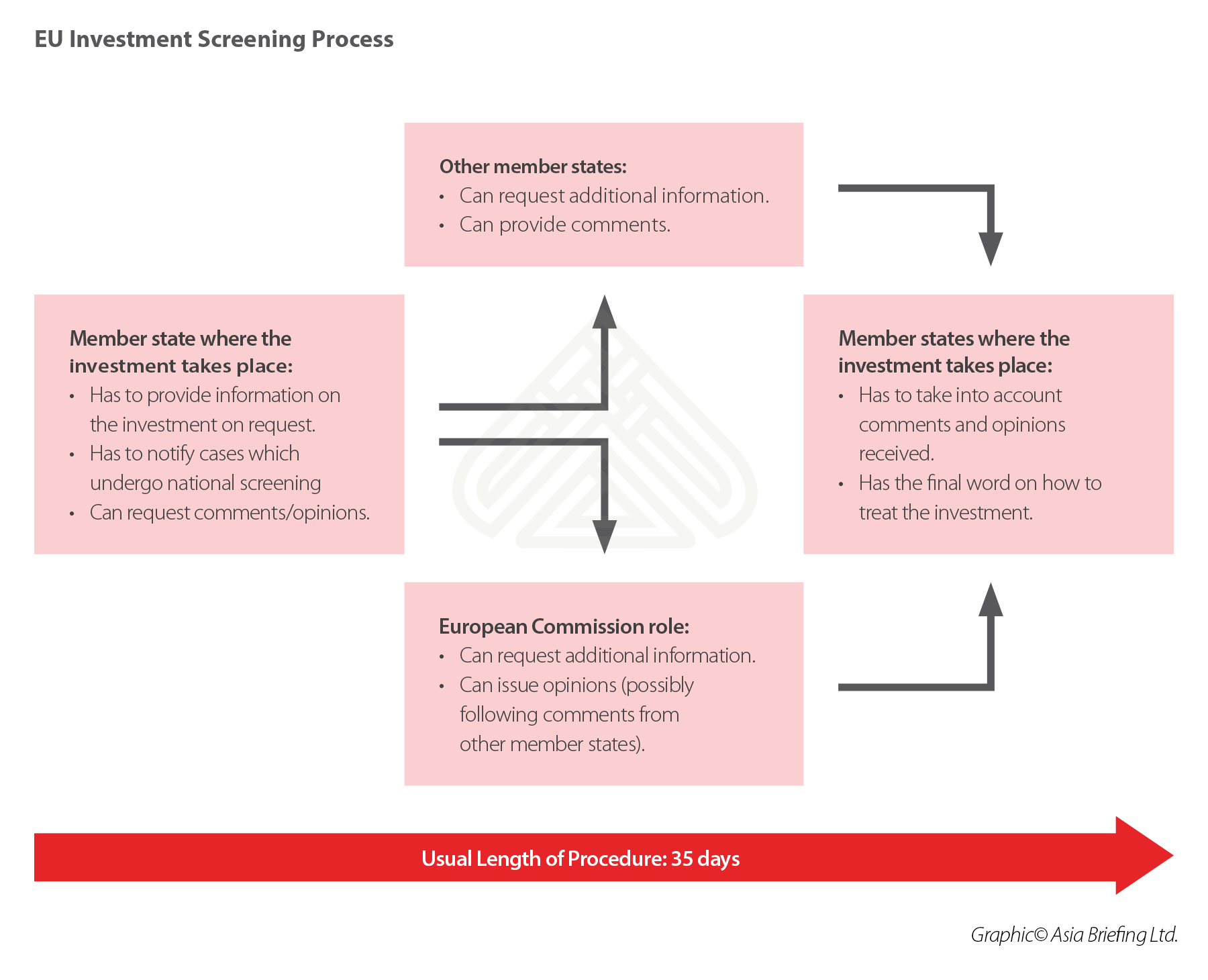

The EU-wide screening policy is a “coordination and cooperation” tool, rather than a tool by which investments can actually be blocked at the EU level.

If member countries believe an investment could potentially impact their national security, they can request information from the country in which the investment is taking place.

They cannot, however, stop that country from making the final decision to accept the investment.

The policy also allows the European Commission to issue opinions on investments that could affect the security of multiple EU member states or the EU itself.

If the Commission issues advice on an investment that it believes will affect the EU, the member state in which it is taking place must justify their decision – should they deviate from the Commission’s advice.

EU member states are required to submit a report on inward FDI activity annually. They are also required to establish a national contact point for FDI matters.

The EU-wide screening policy encourages investment scrutiny based on three criteria that have the potential to affect “security or public order”:

- Investments in sectors considered sensitive;

- Investments as part of “state-led outward projects”; and

- Investments by state-controlled entities.

The policy does not cover greenfield investments, and it does not discriminate based on the investing party’s country of origin.

Nevertheless, it is quite clear that the policy is a response to the perceived threat of Chinese investment.

Investment in sectors considered sensitive

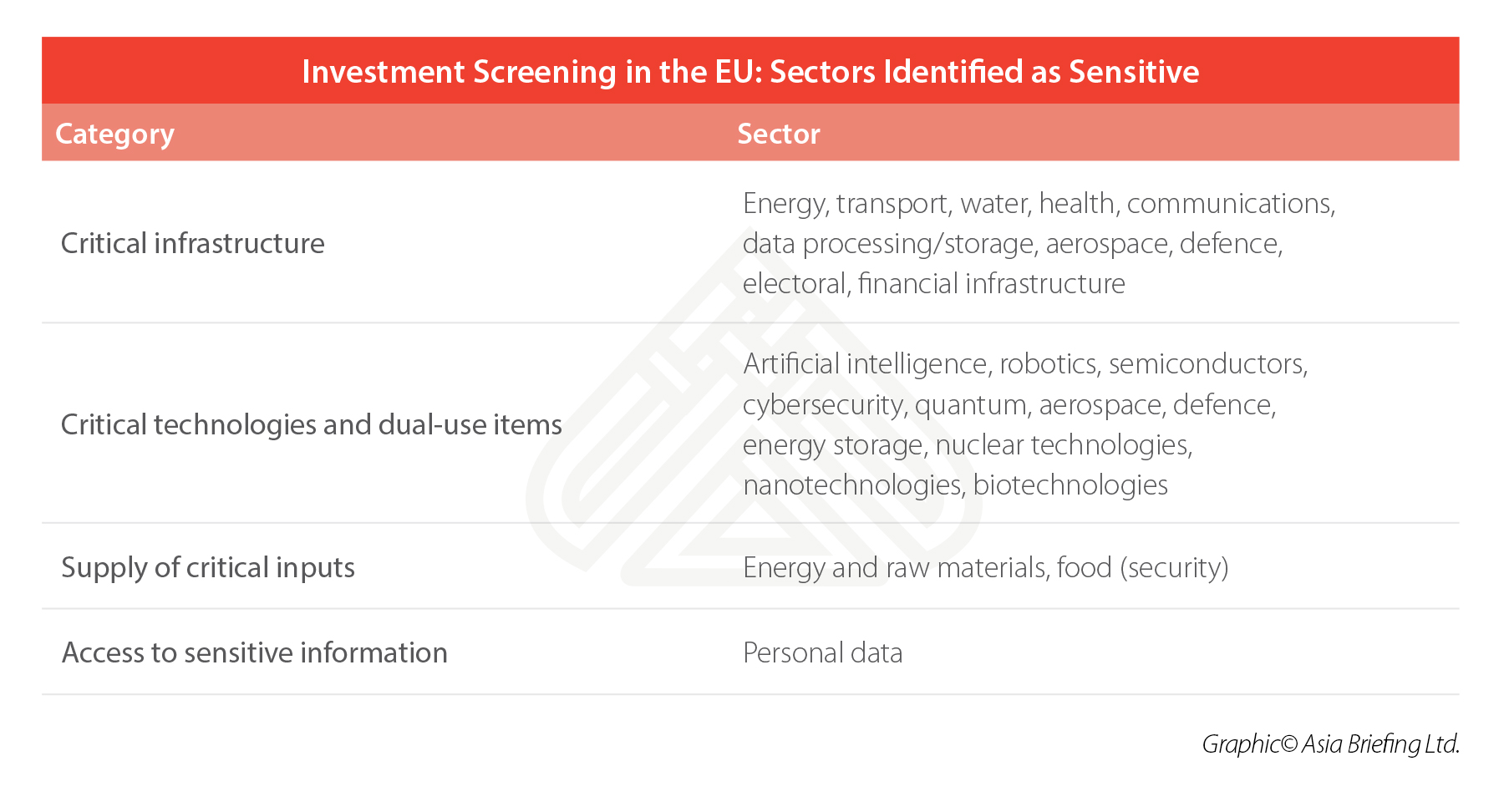

The sectors designated for special scrutiny are extremely broad but mainly fall within critical infrastructure or high-technology.

Investments in these sectors receive increased scrutiny regardless of the kind of investor that is conducting the transaction.

Investments as part of “state-led outward projects”

Investments as part of “state-led outward projects”

Investments as part of state-led outward projects or programs are investments made by either private or public companies that have direct or indirect state-support as part of an overall agenda.

Although the policy does not link this category of investment directly with China’s “Made in China 2025”, it is a clear product of it.

Made in China 2025 is China’s plan to transition the country from a manufacturer of low-end goods to a manufacturer of high-end goods.

What makes it controversial is its ambition to make China the leading high-tech manufacturer in the world, and claims, particularly from the US, that the Chinese want to access intellectual property from foreign manufacturing companies through FDI.

Many of the ten sectors that China’s plan targets for development are included in the list of sensitive sectors in the EU, such as energy, aerospace, transport, and robotics.

Investments by state-controlled entities

The policy also calls for heightened scrutiny of investments by entities that are directly or indirectly state-controlled.

State-owned firms are believed to require more scrutiny because of the risk that investments are motivated by a political rather than business agenda.

Again, this seems to be linked to the influx of Chinese FDI in the EU. From 2000, around 60 percent of all Chinese FDI to the EU came from state-owned entities.

Many EU states also believe that many Chinese private companies have links to the state – for example, due to receiving loans from state-owned banks or having ties to government officials who serve as company board members – allowing them to be directed by state interests.

EU screening policy is unlikely to reduce Chinese FDI

The new screening policy will likely encourage scrutiny on a large amount of Chinese FDI to the EU.

However, the screening policies of individual states and, more importantly, the Chinese government’s own restrictions on FDI outflows will determine the extent of Chinese FDI in the EU.

In 2018, around 42 percent of all Chinese FDI transactions were in sensitive sectors, 24 percent were state-owned entities, and 58 percent were in sectors linked to China’s Made in China 2025 policy.

Despite the large amount of FDI that the policy covers, the impact of this on Chinese FDI levels will be low because transactions cannot be blocked at the EU level.

The screening policies of individual member states and their attitudes towards Chinese FDI will be more decisive in determining FDI levels.

Currently, 13 EU countries have domestic investment screening policies, with four others considering establishing screening regimes.

As more countries establish screening mechanisms in the EU, there may be a small increase in the number of blocked transactions.

Nevertheless, this will not substantially impact the attractiveness of the EU single market for Chinese investors. The EU is the world’s leading destination for FDI and is friendlier towards Chinese FDI than the US.

Where an impact on Chinese FDI is likely to take place, is back in China and the policies that restrict capital outflows.

In 2017, the Chinese government restricted outward foreign investment to help deleverage the amount of debt in China’s banking system. This led to a EUR 8 billion (US$8.99 billion) reduction of Chinese FDI to the EU in the same year.

Whether these restrictions are eased or tightened further depends on the state of the Chinese economy and the success of Chinese debt deleveraging.

Although the EU-wide screening regime is an achievement of EU unity, the central forces that will shape Chinese FDI in the EU lie not with the European Parliament Plenary but with the Chinese government itself.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia from offices across the world, including in Dalian, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Readers may write to china@dezshira.com for more support on doing business in China.

- Previous Article Beijing and Shanghai Remove Bank Account Approval Requirements

- Next Article Evaluación de inversiones en la UE: impacto en la IED china