Shenzhen’s New Data Regulations Explained

Shenzhen has issued milestone data regulations, the first of its kind to be passed by a local government in China. They come in effect January 1, 2022. Service providers must obtain consent from users and there are stipulated limitations on the collection, processing, storage, and transfer of personal data. The Shenzhen regulations also make major inroads into the sharing of public data and tackles the under-regulated data trading market. Some experts have expressed concerns that the regulations conflicts with top-level legislation, which could cause issues in their application.

Shenzhen, a major city in the southern Guangdong Province and a hotbed for technology development and innovation, recently passed the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone Data Regulations (the ‘regulations’), the first of its kind to be released by a regional government in China.

The regulations, established by the Shenzhen Municipal People’s Congress on June 29, come on the heels of the national Data Security Law and the second revision of the draft Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) issued by the central government earlier this year. They are the first local regulations released in China that provide detailed requirements on the implementation of national data protection laws.

The regulations will serve to rein in what is widely seen as unfair and exploitative practices for data collection by requiring service providers to get explicit and informed consent from users and limiting the scope of data usage. The regulations also prohibit apps from refusing core services if users do not give permission to access personal information, and restrict the use of personal data for personalized recommendations and advertisement.

In another landmark decision, the regulations outline provisions for the management and free sharing of public data, as well as new mechanisms for data trading in efforts to create a fairer playing field for the highly under-regulated data trading market. The new regulations will be in force from January 1, 2022.

Below, we outline how the new regulations plan to regulate the use of personal and public data and provide a brief analysis of the impact they may have on foreign companies and investors in Shenzhen.

Note that the regulations refer to the entities collecting and using personal data as ‘data processors’, which is widely understood in the media as being mobile applications. As the regulations may be applicable to a wider segment of the market, for the purposes of this article, we refer to these entities more broadly as ‘service providers’.

The need for better personal data regulation in China

Protection of personal data has been a hot button issue for many years in China, with consumers becoming increasingly frustrated by the lack of control over the data they share with apps and service providers.

Common complaints are that service providers collect data from users without their permission or knowledge, and that they collect far more data than is reasonably required to deliver the services. There is also widespread misuse and mismanagement of the personal data, which may have serious consequences for individual privacy and security.

Amid growing concerns over cybersecurity and online privacy, China has begun taking measures to strengthen its data protection regulations.

In 2017, the country passed the Cybersecurity Law, and in April 2021, released the second draft of the PIPL, which drew upon the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) for inspiration. On June 10, 2021, the central government issued the Data Security Law, containing provisions on the usage, collection, and protection of data in China.

The Shenzhen regulations are significant in that they are the first local regulations to provide guidelines for the implementation of the above-mentioned data security laws. They go further than any other before them in tackling data security issues, providing specific rules for what, when, and how service providers are permitted to collect data. This includes clauses on how much data they may collect and how they are permitted to collect, store, and process the data.

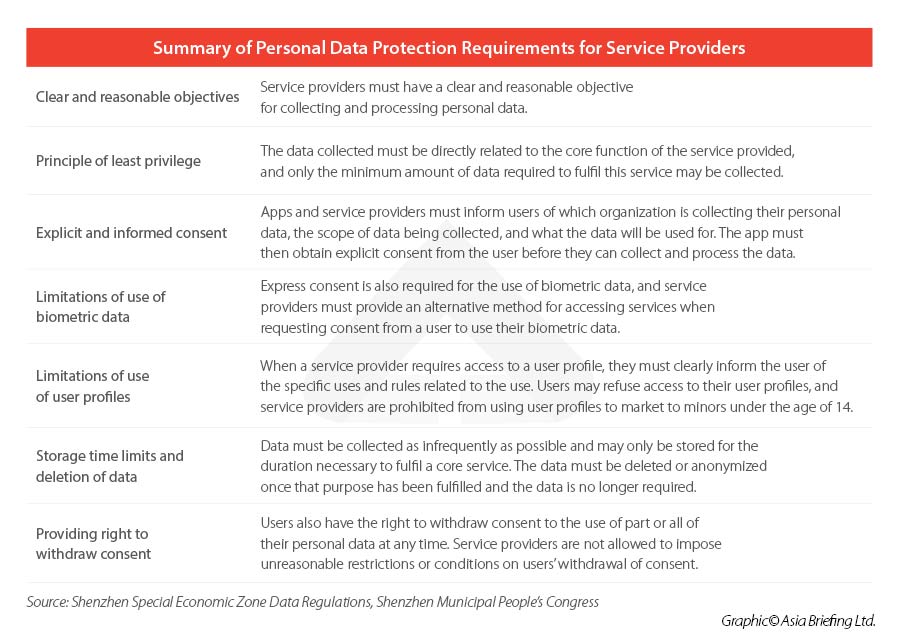

Clear and reasonable objectives

The first requirement that the regulations pose to service providers is the need for a “clear and reasonable objective” for collecting and processing personal data. Service providers must inform the user of the purpose of collecting the data in a clear and easily accessible manner.

The regulations do not specifically define what is considered a “clear and reasonable objective”, but it can be broadly understood as when a service provider has an absolute need to access the personal data in order to provide the core services the user is seeking, which they would otherwise be unable to provide.

Principle of least privilege

In stipulating the scope of data that service providers are permitted to access, the regulations adopt the “principle of least privilege” – that is, the data collected must be directly related to the core function, and apps may only collect the minimum amount of data required to fulfill said core function.

In addition, the principle of least privilege requires that apps establish a mechanism of “minimal access authorization”, which limits the amount of data that the service provider’s personnel can access, only enabling them to access the required scope of data to fulfill a certain task.

Service providers may not refuse services to users who do not consent to the use of their data, except when the data is necessary to offer the services.

The regulations also task the relevant government departments with establishing a reporting and complaint mechanism through which users can flag data privacy breaches or violations.

Explicit and informed consent

Service providers must obtain consent from a user in order to access their personal data. Before a user can consent, the service provider must inform the user of a number of key items.

To receive a user’s consent, service providers must inform them of the following:

- The name and contact of the entity accessing their data

- The type and scope of the data collected

- The purpose and method for processing the data

- Time limits for storing the data

- Any possible security risks associated with storing personal data and measures taken for data security

- The user’s legal rights and means available for them to exercise those rights

Exceptions to consent are given in urgent cases where the service provider is unable to inform the user of the use of their data ahead of time. However, in these circumstances, the service provider must promptly inform the user of the use of their data after the emergency has been dealt with.

Service providers must also obtain explicit consent from a user before they can process any ‘sensitive data’. This type of data is defined as any personal data that may lead to discrimination against a person or harm to their security or property in the event the data is leaked, misused, or illegally obtained.

To obtain consent, the service provider must inform the user of the reason this sensitive data is required, and must prominently warn the user of any risks or impact it could have upon them. The service provider may only process the data that is within the scope of the user’s consent.

The regulations also take on the misuse of personal data of minors under the age of 14 and adults with limited capabilities to provide consent. This is in part handled by classifying personal data from these groups as ‘sensitive data’, and are thus treated under these stricter regulations.

Limitations on use of biometric data

Express consent is required for the use of biometric data, such as genes, fingerprints, voiceprints, palmprints, auricles, irises, and facial features. This is another thorny issue in the discussion on data privacy: technology such as facial recognition or fingerprint verification is widely used for everything from paying for coffee to accessing office buildings, and users often are given no other means of accessing the services they need.

The regulations stipulate that service providers must provide an alternative method for accessing services when requesting consent from a user to use their biometric data, unless biometric data is absolutely necessary for processing the data. This hinders apps from requiring users to use facial or fingerprint recognition to access their services.

Biometric data may also not be used for any other purpose other than the given purpose without the consent of the user, and explicit consent from a legal guardian is also required for the use of biometric data of minors under the age of 14 or adults with limited capabilities to provide consent.

Limitations on use of user profiles

Another area addressed by the regulations is the misuse of user profiles, a collection of data on a particular user that may include key identifiers, such as their name, location, occupation, salary, and even interests and online behavior. These user profiles have long been used by companies to create personalized recommendations of products and services, and sometimes even to engage in price discrimination, often without the knowledge or consent of the user.

Under the regulations, if a service provider needs to use a user profile to provide better products and services, they are required to clearly inform the user of the specific uses and rules related to their user profile.

Users may refuse access to their user profiles and must be provided with a clear and accessible channel through which to do so.

The regulations also outright prohibit service providers from using user profiles to market to minors under the age of 14, unless they have specifically obtained consent from a legal guardian.

Storage time limits and deletion of data

The regulations also place restrictions on the storage of data, stipulating that data must be collected as infrequently as possible, and is permissible only when it is required to fulfill core services. Service providers may only store data for the duration necessary to fulfill the objective, and must delete or anonymize the data once that purpose has been fulfilled.

Users have the right to withdraw consent to the use of part or all of their personal data at any time. The service provider must offer a clear channel through which the user can withdraw their consent and may not use a service agreement or technological means to hinder them from doing so.

Service providers are obliged to provide personal data to the user upon request and may not charge the user for it.

In another effort to curb the misuse of personal data, the regulations require that service providers remove identifiers of personal data if they give it to a third party. The data must be de-identified to the extent that a person cannot be identified without the addition of other data.

Public data sharing

The regulations also confront issues surrounding the sharing of public data. An explainer attached to the regulations quotes Lin Zhengmao, deputy director of the Legislative Affairs Committee of the Standing Committee of the Shenzhen Municipal People’s Congress, as saying that the city’s public data system lacks standardization and suffers from ailments such as small sample sizes, poor data quality, a lack of channels for accessing data, and low user participation.

The regulations seek to address these issues by prescribing the establishment of a data management system and a big data center to help safely and efficiently store, manage, and consolidate public data. The center will also provide an open and free system for accessing public data.

Public data is defined as any data collected while providing education, health, social welfare, water, power, gas, environmental protection, public transportation, or other public services, both by government departments and public institutions.

Under the regulations, government departments must open this data up to the public and may not charge any fees for access.

By creating a more equitable and accessible data system, the local government hopes that both government departments and the private sector can better harness public data to spur digital development in the region.

Data trading and treating data as a ‘factor of production’

At the end of 2019, the central government classified data as a ‘factor of production’, recognizing it as a fuel for the digital economy for the first time. This statement has given legitimacy to the commodification of data.

Fast forward to today, and the data market is still rife with abuses and mired in legislative grey areas. With the huge potential the data market offers, there is an urgent need to regulate and improve business practices in the industry. China is set to be the single biggest producer of data in the world by 2025, overtaking the US, but a lack of oversight risks undermining the value of the data that is being generated.

Shenzhen’s new regulations make efforts to address some of these issues, stating the need to create better mechanisms for data transfers between companies and issue new data legislation, as well as curb unfair practices and competition among companies.

To this end, the government proposes the establishment of a system of data standards for local governments, industries, groups, and corporations, as well as a system for data quality verification and value assessment.

At the same time, the regulations prescribe the establishment of “a statistical accounting system to accurately reflect the asset value of data factors of production, and to promote the inclusion of data factors of production into the national economic accounting system.”

To facilitate data trading, the regulations also urge the expansion of data trading channels to allow market players to freely trade data through legal and regulated platforms, or trade data freely among themselves in a legal manner.

The regulations clearly define data that can be traded as “data products and services that have been created through the legal processing of data”.

The regulations build upon China’s antitrust laws to take aim at unfair competition and misuse of data, spelling out that companies may not use illegal means to obtain data from another company or use data collected illegally from another company to provide alternative products or services.

Companies are also prohibited from using big data analysis to engage in price discrimination. This provision aims to tackle discriminatory practices, such as charging long-term or high-paying customers higher prices than other customers for the same product or service. Violators can be fined up to RMB 50 million (US$7.7 million) for such infractions, depending on the size of the transaction.

Strengthening data security

The regulations also dedicate an entire chapter to data security. Building upon China’s Data Security Law, the regulations clarify data security management responsibilities. They require the municipal government to establish a data security management system, while also tasking service providers with creating their own systems for data classification, risk monitoring, and security assessment and training.

Service providers must also maintain a transparent and traceable record of their data processes so that the legality can be assessed and that the system is transparent and traceable.

The regulations outline specific rules for each stage of the data lifecycle, requiring strict security measures for the collection, processing, storage, sharing, and destruction of personal data or data that has been designated as ‘important’ or ‘sensitive’ by the State. These include, but are not limited to:

- Implementing mechanisms for anonymization and de-identification of data.

- Carrying out hierarchical management of data storage in different domains, and selecting storage carriers that match security performance, protection grade and security level of the data.

- Adopting encrypted storage, authorized access, or other even stricter security protection measures for sensitive personal data and data designated as important by the State.

- Establishing a recovery system for core data and implementing mechanisms for destroying data when required.

- Implementing measures for monitoring data leaks, breaches, damage, loss, and tampering.

- Drafting an emergency response plan for any leaks or breaches, which must be immediately activated in the event of any violation or accident.

- Undergoing regular risk assessments of data that has been designated as sensitive by the state.

Before any personal or important state data can be transferred overseas, it must undergo a “data exit security assessment” and a national security review.

There may be serious consequences for service providers that violate data protection laws. Service providers that violate the law and subsequently fail to correct their infraction or cause serious damage will be investigated for legal responsibility, and both individuals and enterprises can be held liable for the compensation.

Limitations of the regulations

Although these new regulations go further to close loopholes in China’s data legislation, there are a few areas that still fall short or will require further clarification.

One glaring issue is the question of data ownership. The regulations propose the implementation of a “comprehensive reform pilot implementation plan” that aims for Shenzhen to improve data property rights systems and explore new mechanisms for data property rights protection and usage.

However, in the explainer attached to the regulations, Mr. Lin Zhengmao admits that it is difficult to clearly define ‘data ownership’ through local regulations, and simply offers the general consensus that “personal data have the properties of personality rights” and that “enterprises have property rights over data products and services formed through the investment of high levels of intellectual labor”. This ambiguity could cause disputes between companies and inconsistent enforcement of the regulations.

Some experts have also raised concerns that local regulations in Shenzhen may cause a rift in the digital market and conflict with data regulations in other regions, pointing out that the Shenzhen regulations equate ‘personal data’ to ‘personal information’. This is at odds with top-level legislation that separates personal information protection and data usage into two different categories, and could cause disputes in application, especially for Shenzhen-based companies litigating in other regions.

Impact on foreign investors

The new data regulations will be applicable to any private or public entity that uses personal or public data in Shenzhen. It is therefore likely that many service providers will have to review and update their service agreements in order to comply with the regulations, and update user interfaces to enable explicit and informed consent from users.

Companies handling sensitive or state data must also adhere to the strict requirements for data storage and security, ensuring that there are data monitoring, risk assessment, back-up, emergency response plans, data destruction, and other security mechanisms in place.

Foreign investors engage in cross-border data transfer, in particular of personal data or any data that has been designated as important by the state, must also apply for an exit security assessment and pass a national security review before they can transfer the data abroad.

Blazing a trail for data legislation in China

As the government continues to crack down on tech companies for violations of data security laws and anti-competitive practices, it is clear there is a strong desire to strengthen personal data protection and reign in the rampant misuse and mismanagement of data. The regulations have taken a big step in addressing some of these pressing issues, and the impact of their implementation may have a far-reaching impact.

The regulations may also pave the way for the creation of a legal and regulated data market. Home to some of China’s biggest technology companies and 300 big data companies, Shenzhen is an ideal place to cultivate a healthy data trading market and provide more opportunities for companies to tap into this lucrative industry.

In Shenzhen, long a test bed for groundbreaking regulations in the technology sector, the local government has taken the lead in regulating a number of high-tech industries, passing landmark regulations in fields such as artificial intelligence and autonomous driving earlier this year.

The Shenzhen regulations are widely seen as a trial for the creation of other similar rules, and it is likely that other cities will follow suit in the near future.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article How EU Businesses Can Access the €21 Trillion RCEP Free Trade Market via Existing Agreements

- Next Article China’s Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law: How Businesses Should Prepare