2021 China Demographic Trends – What the Latest Data Says

China demographic trends in 2021 show plummeting birth and fertility rates and a rapidly aging society. China’s government has been aware of the slowing population growth and recently stepped up measures to boost birth rates in 2021. We discuss the effect of government policies and measures and the impact that China’s changing demographics will have on companies.

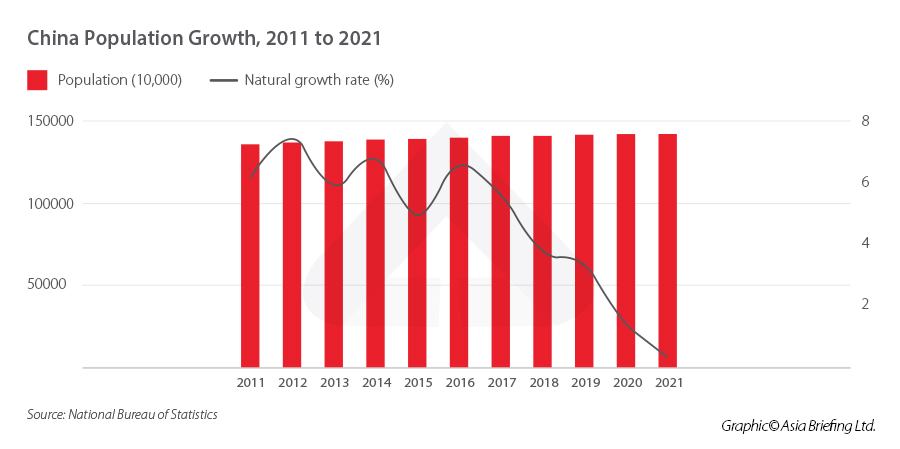

Data released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) in January 2022 showed that the country’s natural population growth rate dropped to the slowest ever recorded increase in 2021. The latest data further raised concerns over the speed of China’s population deceleration and sparked yet more discussion on the impact this will have on China’s long-term economic growth.

China’s aging population has been a topic of discussion for many years and reached a new pitch after the publication of the once-a-decade population census in 2020, which showed the population growth was slowing at an unexpected pace.

Here we take a closer look at China’s latest demographics figures and discuss what is being done to address the impending population decline. We also try to understand what the demographic shift will mean for companies operating in China.

China demographics overview 2021

Declining birth rates

China’s total population reached approximately 1.412 billion in 2021, a net increase of just 480,000 people. That is a natural population growth of just 0.34 per one thousand, down 1.11 percentage points from 2020, and the lowest ever recorded rate.

The birth rate in 2021 was 7.52 per thousand people, a decrease of 1 per thousand people from 2020. Meanwhile, the mortality rate reached 7.18 per thousand people, a slight increase of 0.11 from 2020. This indicates that China’s population growth may reach the tipping point very soon, where the mortality rate exceeds the birth rate, and the population begins to decline.

Aging population and increasing dependency ratio

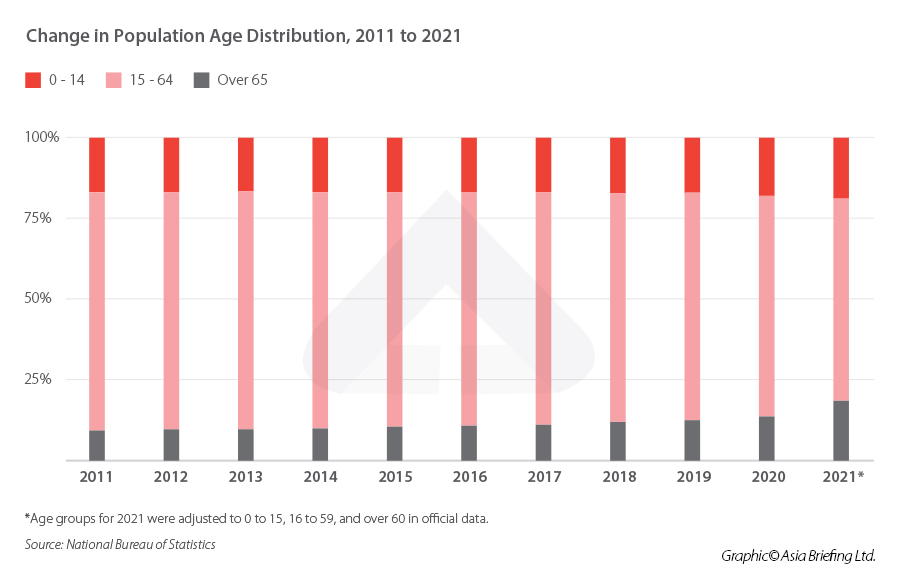

The declining birth rate has led to a rapidly aging society, something which has been well documented and discussed inside and outside of China. The proportion of over 65 years has grown from 9.1 percent of the population in 2011 to 14.2 percent in 2021, indicating a shrinking working-age population.

Note that as of 2021, China’s National Bureau of Statistics has adjusted the age groups to be: 0 to 15 years, 16 to 59 years, and over 60 years.

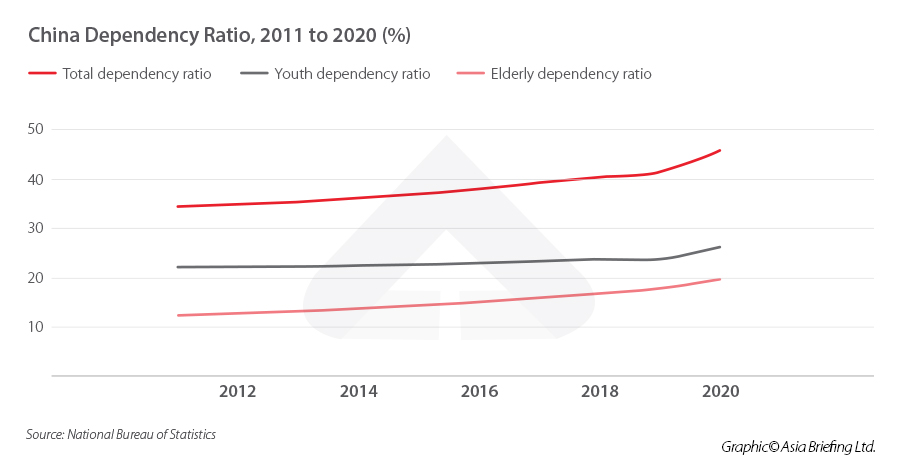

China’s aging population is also reflected in the country’s changing dependency ratio, which measures the ratio of the non-working population (those aged 0 to 14 and over 65) to the total number of working-age people (aged 15 to 64). The overall dependency ratio in China has increased from 34.4 percent in 2011 to 45.9 percent in 2020, according to the latest data available.

This is still considerably below the dependency ratios of many developed nations, such as Germany and Japan, which had dependency ratios of 55 percent and 69 percent, respectively, in 2020, according to the World Bank. However, the concern stems mainly from the speed at which the dependency ratio is increasing in China.

Why is China’s population rate falling?

According to the NBS, the low birth rate is due primarily to a decrease in the number of women of childbearing age, and a sliding fertility rate. In 2021 there were approximately 5 million fewer women of childbearing age (those between the ages of 15 and 49, per the bureau), which includes about 3 million fewer women between the ages of 21 and 35. Meanwhile, fertility rates are decreasing as women get married and have children at a later age, with the average childbearing age now two years older than it was 10 years ago.

The population decline may also have been accelerated by the pandemic. Slowing economic growth and disruption caused by the pandemic mean households have lower disposable income, which may have further disincentivized people from having a first or second child.

From a broader perspective, China’s slowing population growth has historically been caused by the one child policy, which until 2015 prohibited most couples in China from having a second child. The limit on the number of children was first eased to allow two children in 2015 and then again to three children in 2021.

However, the easing of the one child policy to allow two children per couple in 2015 did not translate to an increase in births, and it is therefore uncertain that increasing the limit to three children will have any impact.

That is because there are many other factors keeping the birth rate and fertility down, some of which are typical trends seen in many industrialized and newly industrialized countries. Increased participation of women in the workplace and changing attitudes toward marriage means people are less inclined to have children. In addition, the rising cost of living and changing expectations toward quality of life and lifestyles means that people are less willing – and capable – of taking on the burden of childrearing.

Boosting population growth – three-child policy and better childcare benefits

As mentioned previously, China’s aging population and imminent population decline is something that the government has been aware of for many years and has taken steps to address.

Several measures have already been taken to try to boost birth rates, such as the implementation of the three-child policy in 2021, allowing couples to have up to three children.

Besides upping the limit on the number of children that couples are permitted to have, the Chinese government has also begun implementing a series of policies to help ease the burden of having children. Several cities across China have imposed better maternity, paternity, and childcare benefits, such as increased maternity leave and childcare leave, to help new parents and young parents with the burden of raising children.

2021 also saw the introduction of a raft of measures and policies aimed at reducing the cost and burden of childrearing. This includes sweeping education reforms that effectively banned private tutoring in core subjects to reduce the cost of education. The ultimate goal is to cool the competitive nature of China’s education system that pressures parents to spend vast amounts of money on extracurricular classes, private tutoring, and cram schools in order to ensure their children’s futures.

A cap on house prices in major cities, such as Shenzhen, has also been implemented to reduce the cost of living for young couples. House prices in China, in particular in major cities, are notoriously high – over RMB 60,000 per square meter in Shanghai and Shenzhen – contributing to the notion that life is too expensive for a child.

However, these moves have been undermined by turbulence in China’s property market that has led to falling house prices, and as much of China’s personal wealth is tied up in property, led to more uncertainty.

At the other end of the spectrum is the issue of retirement age. China’s statutory retirement age is relatively young at 60 for men and 50 to 55 for women. For comparison, the statutory retirement age in both Japan and Germany is 65, and both countries plan to raise it further in the next 10 years.

In early 2021, China released its 14th Five Year Plan for economic development in the period between 2021 and 2025. In it, it proposed “gradually delaying the statutory retirement age” but does not detail when and to what age the retirement age will be raised. Despite this, the announcement was met with a great deal of backlash, and it is uncertain whether the government will go through with the decision.

It bears mentioning that, despite the low statutory retirement ages, many people, and in particular lower-income workers, work far beyond this age. And as a shrinking working-age population means less tax going toward pensions, it is likely that more and more people will have to work beyond the retirement age in order to make a living, as is the case in many developed societies.

Ultimately, without an increase in immigration – which China still strictly controls – the answer to China’s demographic problems will be increased productivity. This will stem both from an increase in automation to free working-age people from remedial, low-skilled jobs, and investing in upskilling and vocational training to help China’s workers pivot to more high-skilled positions.

What does population decline mean for companies in China?

From the perspective of employers, China’s changing demographics will mean having to shift to new employment models and HR strategies for attracting and retaining talent.

Higher employee retention will be key for companies to sustain high-quality growth. This will involve a combination of better employee benefits, opportunities, and upskilling or retraining. We have previously written about how to better retain employees amid a growing labor shortage.

Changing demographics and rising wages may also mean that more low-end manufacturing will move to lower-income countries, while China will become increasingly competitive in advanced manufacturing and high-precision machining.

The aging population also presents several growing market opportunities in the so-called “silver economy” for early movers. These include healthcare, which is fairly underdeveloped in China in many fields. This is reflected in recent government pilot plans to improve elderly care services, which urges local governments to increase the number of healthcare facilities for the elderly and improve elderly services.

High-tech industries, such as robotics, precision machinery, driverless vehicles, and related IT and software solutions that will aid China’s transition to a high-productivity society, will also be in increasing demand as will the talent and training needed to develop and operate such technology.

Development of sectors like professional services will be viewed favorably as they will assist China’s transition to a services-oriented economy; verticals like talent training and upskilling will be key to the longevity of companies.

For advice on how to craft forward-looking HR policies to better attract, retain, and train talent in China, you can speak to our HR professionals by reaching us at China@dezshira.com.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article China’s FDI Hit Record High, Global FDI Rebounds in 2021

- Next Article German Chamber’s Business Confidence Survey 2021/22: Long-Term Outlook is Positive