GDPR Versus PIPL – Key Differences and Implications for Compliance in China

China’s PIPL shares similarities with Europe’s GDPR, but the two do not perfectly overlap. Foreign companies in particular must be aware of the differences between the respective regulations to ensure cyber data compliance. We compare the PIPL vs GDPR and discuss the steps that companies should take to be compliant.

As a professional compliance service provider with solid experience in IT compliance in China, one of the questions we get asked most often from our clients is: Are we compliant with the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) if we are already compliant with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR)? What should we do to be compliant with the PIPL if we are not yet?

Our answer is normally: “It’s good that your company is already GDPR-compliant as a similar methodology for compliance can be used for the PIPL, especially considering that the PIPL ‘borrows’ some concepts from the GDPR. However, there are still some important differences between the GDPR and the PIPL. Those differences, plus the unique business, regulatory, and IT environment in China, can create big challenges for foreign companies in China.”

So, what are the differences between the GDPR and the PIPL and why do those differences pose compliance challenges for companies? We seek to explain these issues in this article.

Differences between the GDPR and the PIPL

The PIPL’s applicable scope

| PIPL vs GDPR – Applicable Scope | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

The first question we would like to raise is how to confirm whether the PIPL applies to a given business activity. In other words, whether or not a company has any legal obligations under the PIPL when the company is doing business in China. From a legal perspective, we call this the “territorial scope” and the “material scope”.

The GDPR focuses more on the “establishment” of the company which conducts business that involves the processing of personal information (PI), and most of the time, this “establishment” usually means where the company is set up. If the company is set up in the EU, all PI processing activity carried out by the company – regardless of whether it is within the EU or outside the EU – will be regulated by the GDPR.

In contrast, the PIPL focuses more on where the PI processing activity takes place. If the PI processing activity occurs within the territory of China, either by a company in China or a foreign company without an office in China, the PIPL is applicable. That means if a company established in China processes the PI of people in other countries, such as in an ASEAN country, the PIPL does not apply to the company’s processing activity, as it does not take place in China and it is not processing the PI of the people in China. Considering how stringent the PIPL is, this offers a certain amount of leeway for companies that rely on the large-scale processing of PI to operate in other countries, especially if the local PI protection laws are looser than the PIPL.

Both the GDPR and the PIPL are extraterritorial, meaning that companies outside of the territorial jurisdiction area (that is, outside the EU and China, respectively) still need to obey the PI laws if they provide services or products to consumers or monitor people within the territorial jurisdiction of the laws.

Definition of personal information (PI)

| PIPL vs GDPR – Definition of Personal Information | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

Both the GDPR and the PIPL have a similar definition of PI, but the PIPL explicitly excludes “anonymized” PI from the definition.

An important difference between the GDPR and the PIPL is the scope of “sensitive” PI (defined in the PIPL) and “special category data” (defined in the GDPR). The scope of sensitive PI under the PIPL is much broader than the special category data under the GDPR.

Meanwhile, the GDPR lists all special category data in a clear way, making it easy for companies or individuals to identify whether or not the PI they are processing falls within this category. The PIPL’s definition is more descriptive but does not include a full list as the GDPR does. Article 28 of the PIPL specifies that sensitive PI is “PI that is likely to result in damage to the personal dignity of any natural person or damage to his or her personal or property once disclosed or illegal used”. This is followed by a non-exhaustive list, which includes biometric data, information on religious beliefs, “specific identity”, medical health, financial accounts, and whereabouts and location, plus any PI of minors under the age of 14.

The fact that financial account information is categorized as sensitive PI came as a surprise to many foreign companies as it implies that almost any business activity involving a payment transaction would involve the processing of sensitive PI. The company can refer the national standard number GB/T35273-2020 (link in Chinese) to better understand the detailed scope of sensitive PI defined by the PIPL.

The GDPR treats the PI of minors under the age of 16 as special category data (though specific EU member countries have different rules on age limits, with some lowering it to 13) while the PIPL specifies the age of 14, which means high-school students’ personal info will not be treated as sensitive PI by default.

Another more important difference in the definition scope between the GDPR and the PIPL concerns deceased persons. The PIPL does not apply to the PI of deceased people as the GDPR does. However, the PIPL allows a close relative of a deceased person to duplicate or request access to relevant PI. They also have partial rights to copy, correct, or delete any relevant PI for their own lawful or legitimate interests.

It is important to note that the rights mentioned above can only be exercised under specific circumstances. One such circumstance is where incorrect PI could cause reputational damage to the deceased person and those close to them. Another example is when a family member wants to log into an email account of the deceased person. In both of these cases, the close family member can request access to the information of the deceased person.

Definition of roles

| PIPL vs GDPR: Definition of Important Roles | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

Differences between data controller, processor, PI handler, and entrusted party

Article 4 of the GDPR defines two important roles related to PI processing: The data controller, who determines the purpose and means of the processing of personal data, and the data processor, who processes the personal data on behalf of the controller. This is a clear and easy-to-understand definition. In certain situations, the role of the controller and processor could be fulfilled by the same person or entity, or there could be multiple controllers (known as “joint controllers”) when two people or entities make decisions together.

Meanwhile, the PIPL defines the roles differently, specifying the role of a “PI handler” (“handler”). In some circumstances, the scope of the handler’s responsibilities are the same as that of both the controller and the processor (as defined in the GDPR). In certain scenarios, the handler can entrust a third-party body to process the PI on behalf of them, in which case the handler would play the role of controller in the GDPR, while the entrusted third party plays the role of the processor in the GDPR. However, this also means that the responsibilities shared between the handler and the entrusted third party are not only regulated by the PIPL, but also by the Civil Code, which stipulates the liabilities of the third-party body, as well as other obligations specified in other laws, such as the Cybersecurity Law (CSL) or the Data Security Law (DSL), as specified in Article 59 of the PIPL.

Data protection officer versus person in charge of PI protection

The GDPR also defines the role of a data protection officer (DPO), clearly describing their tasks, position, and designation conditions. Under the context of the GDPR, the DPO will advise and monitor the personal data protection work inside the organization, as well as the communication work with the data protection agency (DPA). The DPO role can be played by a third-party service agency, and the DPO is not liable for the results or performance of their job.

The PIPL, meanwhile, defines two roles similar to the DPO, but with some slight differences. One of them is named “the person in charge of PI protection” when the amount of PI processed by a company reaches a quantity threshold defined by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). (This threshold is set in the national standards number GB/T35273-2020 as the PI of over 1 million people, the sensitive PI of over 10,000 people, or where “the company’s main business is processing PI and employs more than 200 staff members”).

The role of the person in charge of PI protection can be filled by internal or external personnel. However, unlike the role of the DPO, it can’t be filled by a service agency, as Article 52 of the PIPL requires that the company reports the name of the personnel to the supervisory authorities. Also, note that the CSL requests network operators to appoint a “person in charge of cybersecurity”. A company can appoint the same person to play both the roles of the person in charge of cybersecurity and the PI protection in order to meet the requirements of the PIPL and the CSL.

Another role is the representative of the company, who is responsible for providing services or products to natural persons within China when a company doesn’t have an office in the country. This representative should be a natural person and their name and contact information must be reported to the supervisory authorities. However, this representative is mainly responsible for maintaining communication between the company and supervisory authorities. No other obligations or responsibilities are defined in the law.

Article 58 of the PIPL also subjects big internet platforms to special obligations, known as a “gatekeeper”. The gatekeeper is an independent PI protection agency with external experts that are required to monitor the company’s PI protection activity. The GDPR does not have any corresponding requirements.

Legal basis for processing PI

| PIPL vs GDPR: Legal Basis for Processing PI | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

Having discussed the applicability, the defined scope of PI, and the defined roles in the PIPL and GDPR, we will now look at the conditions under which a company can process the PI under the two laws.

Both the GDPR and the PIPL set common basic principles for PI processing, such as lawfulness, fairness, and transparency, among others. However, from a legal perspective, there are still few differences between the legal bases upon which companies are permitted to process PI in the GDPR and the PIPL.

Consent from individuals or data subjects is one common legal basis for processing PI under both the GDPR and the PIPL. However, the PIPL stipulates more requirements for consent based on the sensitivity of the PI and the scenario in which the processing is conducted. For example, the PIPL requires the PI handler to obtain separate consent from individuals when processing sensitive PI, or in scenarios such as sharing the PI with another party or transferring it outside of China. This means the company needs one general consent form plus several special consent forms for these scenarios. We believe this will be a common requirement for many foreign companies that use IT systems hosted in overseas headquarters.

The GDPR allows companies to process PI for the purpose of legitimate interest pursued by the controller or by a third party. However, there is no similar legal permission specified in the PIPL. On the other hand, the PIPL explicitly allows the processing of PI for news reporting without getting the individual’s consent, which is good news for journalists or professionals in the field.

Even when the company is permitted to process PI without obtaining the consent of the subject, such as when required to meet a legal obligation, it doesn’t mean the company can process the PI without notifying the individual or data subject. The obligation to notify is always applicable for the PI handler under the PIPL, except in cases where laws and regulations restrict the notification of the individual for confidentiality reasons, or where the individual has made their PI public already.

We have been asked by some companies whether or not they need to obtain consent from employees before they can process their PI for the purposes of recruitment or fulfilling contracts. We would like to remind readers that most foreign companies should consider using consent as the legal basis for processing the PI of employees, rather than quoting Item 2 of Article 13, which stipulates “implementation of human resource management in accordance with the collective HR contract” as a legal basis for PI processing. This is because the “collective HR contract” is rarely used and has specific requirements, such as the approval of labor unions or worker’s congresses.

DPIA and PIPIA

| PIPL vs GDPR – Data Protection Impact Assessment | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

The GDPR requires companies to perform a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) when the company is going to apply new technology to process the PI and poses a high risk to the data subjects. Some such scenarios include: 1) systematic and extensive evaluation based on automated processing, including profiling; 2) processing special data on a large scale; or 3) systematic monitoring of a publicly accessible area on a large scale.

The PIPL has similar assessment requirements but calls it a Personal Information Protection Impact Assessment (PIPIA). It also provides a more detailed description of the requirements:

- When the PI handler is processing sensitive PI.

- When the PI handler is conducting automated decision-making using PI.

- When the PI handler is entrusting others to process PI, providing PI to other PI handlers, or publicizing PI.

- When the PI handler is transferring the PI outside of China.

- When the PI handler is performing any other PI processing activity that has a significant impact on personal rights and interests.

Based on the above requirements, we conclude that almost all companies would need to consider performing PIPIA to comply with the PIPL, especially when considering the wider scope of sensitive PI. Moreover, many foreign companies use IT systems based in overseas headquarters, which means they often have to transfer data outside of China or share data across borders.

The requirements of conducting a PIPIA are similar to conducting a DPIA under the GDPR. Both processes require companies to identify the purpose for processing PI, the potential risks to individuals, and whether the company has taken the appropriate control measures for protecting the PI. However, companies should be aware that the PIPIA report and handling records must be kept for at least three years.

Cross-border data transfer

| PIPL vs GDPR: Cross-Border Data Transfer | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

Cross-border data transfer (CBDT) is a major concern for foreign companies doing business in China. CBDT is closely related to another term – data localization. To achieve complete and strict data localization, a company needs to build independent IT facilities or infrastructure in China to isolate the data from its overseas offices, including the headquarters. Please be reminded that even remote viewing of data saved in China from an overseas office falls under the definition of CBDT, as viewing is also considered a kind of data processing from a technical perspective. We understand the challenges of maintaining two different IT systems for companies and therefore provide a deep dive into the topic here.

We would first like to point out that CBDT is allowed under specific conditions in the PIPL, and most foreign companies will not need to build standalone IT infrastructure in China for data localization. However, compared to the GDPR, the PIPL is still quite ambiguous in certain aspects when it comes to CBDT-related requirements.

Let’s first recap the related rules on CBDT under the GDPR. The GDPR allows for CBDT in the following scenarios:

- Transfers on the basis of an adequacy decision – the company can transfer PI to any country without further authorization if the EU Commission has decided that the country ensures adequate PI protection already.

- Transfers subject to appropriate safeguards – if the recipient country does not provide adequate protection of personal data according to the EU Commission, then the GDPR offers several other options, including legally binding and enforceable instruments between public authorities, the standard contractual clause (SCC), and the Binding Corporate Rules (BCR). The third option is specifically used for multinational corporations (MNCs) and regulates data transfers between global offices in different countries.

- Derogations for specific situations – in cases where neither of the above conditions are met, the GDPR still allows a company to transfer data outside of the EU once:

- It has obtained the explicit consent for the transfer from the data subjects;

- The transfer is necessary to fulfill a contract between the data subjects and the data controller; or

- The transfer is necessary for public interest, the vital interest of the data subjects or other stakeholders, or other legal grounds for processing PI stipulated in the GDPR.

Compared to the relatively low limitation on free data flow and transfer under the GDPR, CBDT in China is subject to stricter requirements. This is not only due to requirements in the PIPL, but also other laws and regulations, such as the CSL and the DSL. For example, as stipulated in the CSL and the DSL, PI or “important” data collected by Critical Information Infrastructure Operators (CIIO) must be stored within China, unless a national security assessment is passed. Other regulations, such as the Measures for the Security Assessment of Outbound Data (Exposure Draft) and the Cybersecurity Review Measures, further specify the threshold for the amount of PI that can be transferred before a security assessment is required. These measures specify the PI of 1 million people or the sensitive PI of 10,000 people as the threshold before a security assessment is required to be permitted to transfer the data outside of China.

The requirements in the related laws and regulations described above make it seem as though CBDT is near impossible in China. However, the good news is that the PIPL clearly permits the CBDT of PI under the following conditions (though further clarification on the detail is still required from the authorities):

- The company passes a security assessment organized by the CAC.

- The company is certified by a specialized agency for the protection of PI in accordance with the provisions of the CAC.

- The company enters into a contract with the overseas recipient under the standard contract template formulated by the CAC.

If compared to the GDPR, we could say that the “security assessment” of the PIPL is similar to the “adequacy decision”. The main difference is that the GDPR implements the requirements by country while the PIPL implements them on a case–by–case basis. The “contract” in the PIPL is similar to the SCC in the GDPR.

So that clears that up, right? Not quite – the regulations only outlined the principal rules and provide no detailed explanation for the procedures. The CAC has not yet published a contract template, and no one knows where to locate a “specialized agency” for accreditation. Meanwhile, the security assessment appears to be only applicable to large companies. Most companies will therefore continue to face big challenges when it comes to complying with the CBDT requirements of the PIPL.

Supervisory authorities

| PIPL vs GDPR – Supervisory Authorities | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

The GDPR requires each EU member country to establish its own supervisory authority for the protection of PI. It also regulates the competence of lead supervisory authorities when there are multiple supervisory authorities in to maintain consistency. This means that companies usually only need to deal with a single supervisory authority when running a business in an EU country.

The situation is more complex in China as there are multiple authorities with the power to enforce PI protection requirements, and different laws and regulations overlap and appoint different supervisory bodies. The three main supervisory agencies for information security and PI protection in China are:

- The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC): The CAC sits at the top of the overall regulatory framework and usually plays the role of the coordinator between different departments. However, more and more law enforcement-related activities are being done by the CAC directly. The CAC is also responsible for formulating supplementary departmental rules to the PIPL and other laws and organizing the important national security reviews. Most law enforcement cases related to PI have been handled by the CAC, even before the PIPL came into effect.

- The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT): The MIIT oversees the management of industries, especially the telecommunications industry. Permissions for operating telecommunications businesses, including obtaining ICP licenses and ICP filings, fall under the purview of the MIIT. The MIIT is also responsible for taking action on non-monetary penalties, such as shutting down access to IT systems or websites, delisting mobile apps from the app store, and so on.

- The Ministry of Public Security (MPS): The core responsibility of the MPS in the field of cybersecurity and PI protection is the enforcement and supervision of the Multiple Layer Protection Scheme (MLPS). The MLPS requires companies to follow up on specific processes for evaluating and grading the “importance” of their network (from level 1 to level 5) and then implementing corresponding protection measures. The MPS is also in charge of handling cybersecurity breaches, and companies are required to immediately report to the MPS when a security breach happens.

In short, companies need to understand the different responsibilities and communication channels of the different supervisory authorities when undergoing or following up on compliance procedures in China.

Consequences for non-compliance – punishments for both companies and individuals

| PIPL vs GDPR: Consequences for Non-Compliance | |

| Similarities |

|

| Differences |

|

The penalties under the GDPR are very high. The maximum penalty is EUR 20 million, or 4 percent of the company’s total global annual turnover, whichever is higher. The PIPL also imposes very high penalties, with a maximum penalty of RMB 50 million (~US$7.4 million), or 5 percent of the company’s turnover from the previous year. However, the PIPL doesn’t specify whether the turnover is global or just domestic, which could be good news for MNCs.

The biggest difference between the consequences for non-compliance in the GDPR and the PIPL are as below:

- The PIPL may impose other penalties in addition to a fine, which could significantly hamper the company’s business. These include shutting down access to IT systems or websites, delisting the company’s mobile apps from app stores, business suspension, revoking permissions for specific business activities, or in the worst-case scenario, outright revoking the company’s business license.

- The PIPL not only punishes the company, but also the individual who is responsible for PI protection. In the above section on the different PI protection roles, we described the role of “the person in charge of PI protection”. Under the PIPL, this person is held equally liable for non-compliance as the company and could be fined as much as RMB 1 million (~US$150,000) for transgressions. Moreover, they can be prohibited from taking up the role of a senior executive or the person in charge of PI protection for a certain period of time.

Implications and considerations for compliance planning

Back to the question we raised at the beginning of this article. We do believe that companies that are already compliant with the GDPR will be at an advantage as similar concepts are applied in both the GDPR and the PIPL. Similar processes and procedures can also be taken to be compliant with both sets of regulations. However, by analyzing the difference between the GDPR and the PIPL, we can see that companies still need to put in a considerable amount of effort to comply with the PIPL as well as other related compliance requirements, even if they are GDPR-compliant already. Here we list a few key points for companies to consider when following compliance processes in China.

Understanding the complexity of regulatory frameworks

China has a complex legal framework, which includes laws (regulated by the National People’s Congress), regulations (regulated by the State Council), department rules (regulated by the different ministries), and local regulations and nominative documents (regulated by local governments). Many people are aware that the PIPL, the CSL, and the DSL form China’s legal cybersecurity and PI protection regime. However, they may not be aware that these three laws are only part of the overall regulatory framework, and that more details on compliance requirements and guidelines are “hidden” in other regulations.

Moreover, there are also several national standards that need to be carefully considered for compliance. Even though some of these standards are not mandatory, there have been cases where supervisory authorities have referred to them when enforcing the law.

Resources required for compliance

In order to comply with the PIPL (and other laws and regulations on cybersecurity and PI protection), companies not only need to understand the law itself but also require strong technological expertise. On the one hand, the company needs a local legal expert to understand the complex regulatory framework and identify the applicable compliance requirements for business activities. On the other hand, compliance work will also require the expertise of technology professionals, as the data or PI reside inside IT systems. Figuring out IT practices and data flow without sufficient technical knowledge would be a huge challenge.

Meanwhile, the location and architecture of the IT infrastructure may dramatically impact compliance processes. For example, to meet potential data localization requirements, standalone IT infrastructure may need to be set up in China. This would pose a big challenge for companies using universal platforms for global operations. In other words, the IT infrastructure used will also determine the complexity of compliance procedures as well.

Therefore, having both legal and technological expertise is critical for the success of compliance projects. However, we have seen many companies struggle to achieve this as resources allow for only one or the other, and it is rare for a company to have both legal and technology experts. Companies need to consider providing more interdisciplinary training to internal staff in order to cultivate the combined expertise. Moreover, effective coordination between IT and legal departments will be necessary. Companies can of course also seek help from external service providers, with emphasis put on the capacity for combined legal and technological expertise when selecting a vendor.

Planning and implementing an action plan

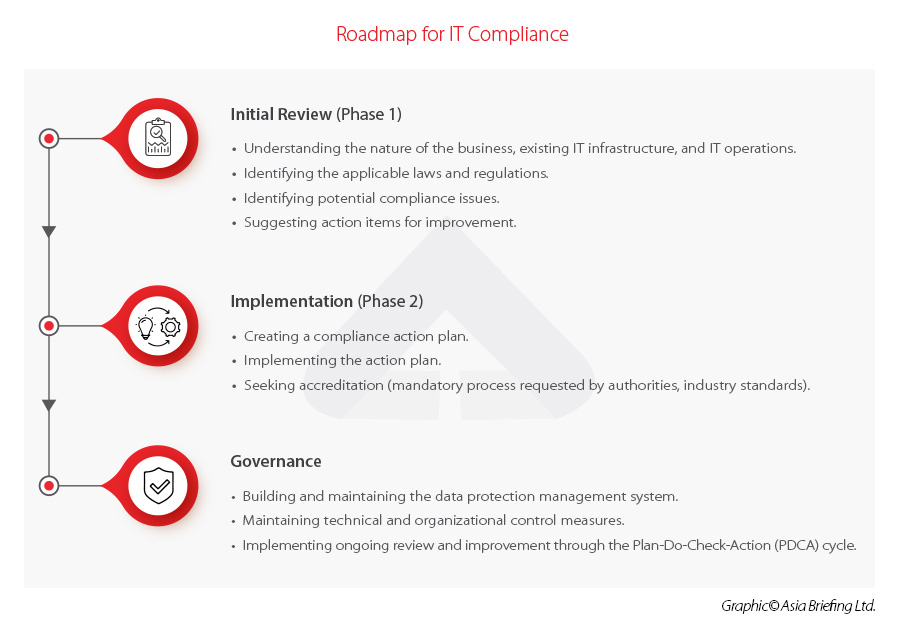

A thorough analysis is a good starting point for compliance, but the key is taking action. The most important thing is not to panic when faced with the complexity of China’s regulatory environment and the consequences of noncompliance. However, we urge companies against inaction and advise them not to passively wait for further detailed guidelines. A prompt action plan should be created and followed to set out on the path toward meeting compliance targets. Below is a template roadmap toward achieving compliance in China.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article How to Make Your Business in China an Attractive Workplace for Gen Z

- Next Article Vocational Education in China: New Law Promotes Sector’s Growth