Chinese FDI in the EU’s Top 4 Economies

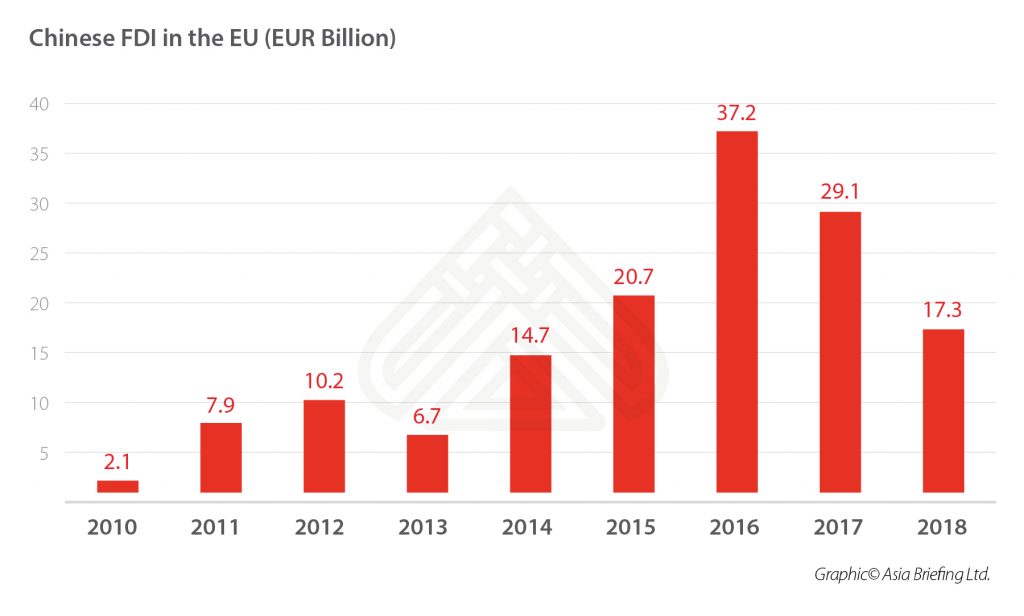

Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the European Union (EU) has increased over 17 times from 2010 to 2016. This was followed by a drop in investments due to controls introduced on capital outflow by the Chinese government in the last two years.

With this large increase and a convergence of investment in sectors like energy and technology, several EU member states have come to suspect an underlying political motive.

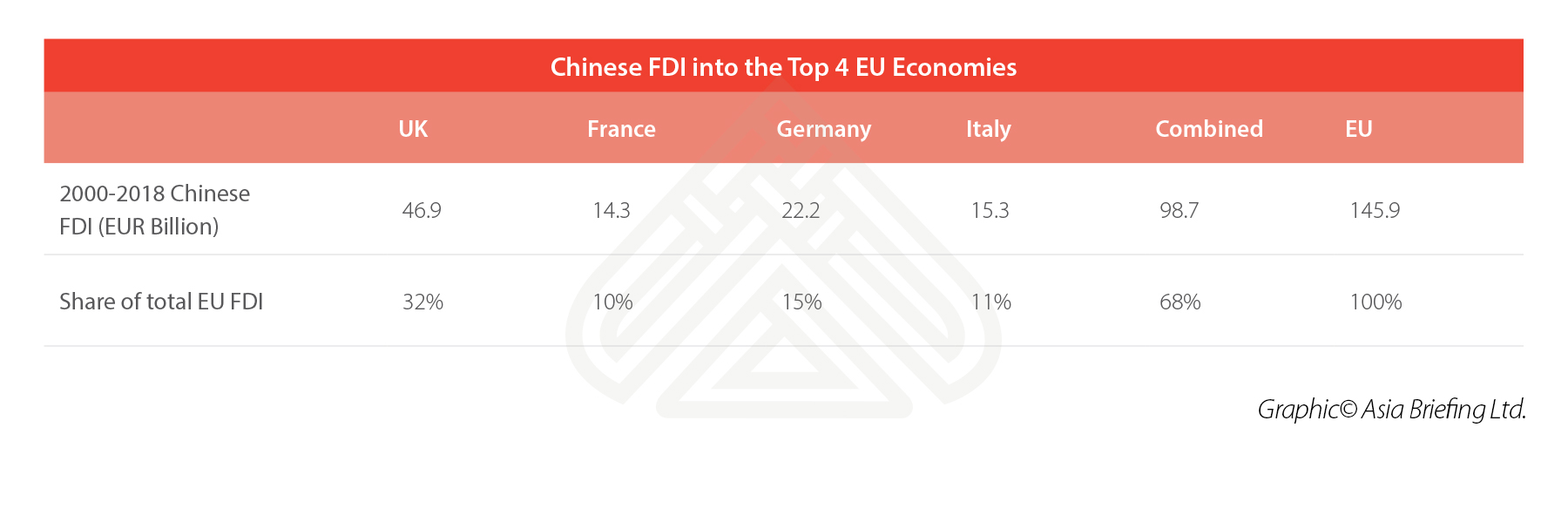

Much of this suspicion has been felt within the EU’s four largest economies – the United Kingdom (UK), France, Germany, and Italy – who have received 70 percent of all Chinese FDI in the EU since 2000.

As a result, all four countries have tightened their investment screening policies. However, Italy’s newly-formed government is substantially more pro-China than the last, which will likely lead the country to increase its share of Chinese FDI in the future.

What investment screening looks for

Foreign investment is a key source of capital for most countries, and especially so since the global financial recession of 2008.

Many countries, however, have in place an investment screening process for national security reasons.

These screening processes often examine incoming FDI in sensitive sectors and consider the investor’s connections to foreign states with whom the destination country has troubled relations.

In the EU, the UK, French, German, and Italian governments all have the power to block certain investments if they are considered a security risk.

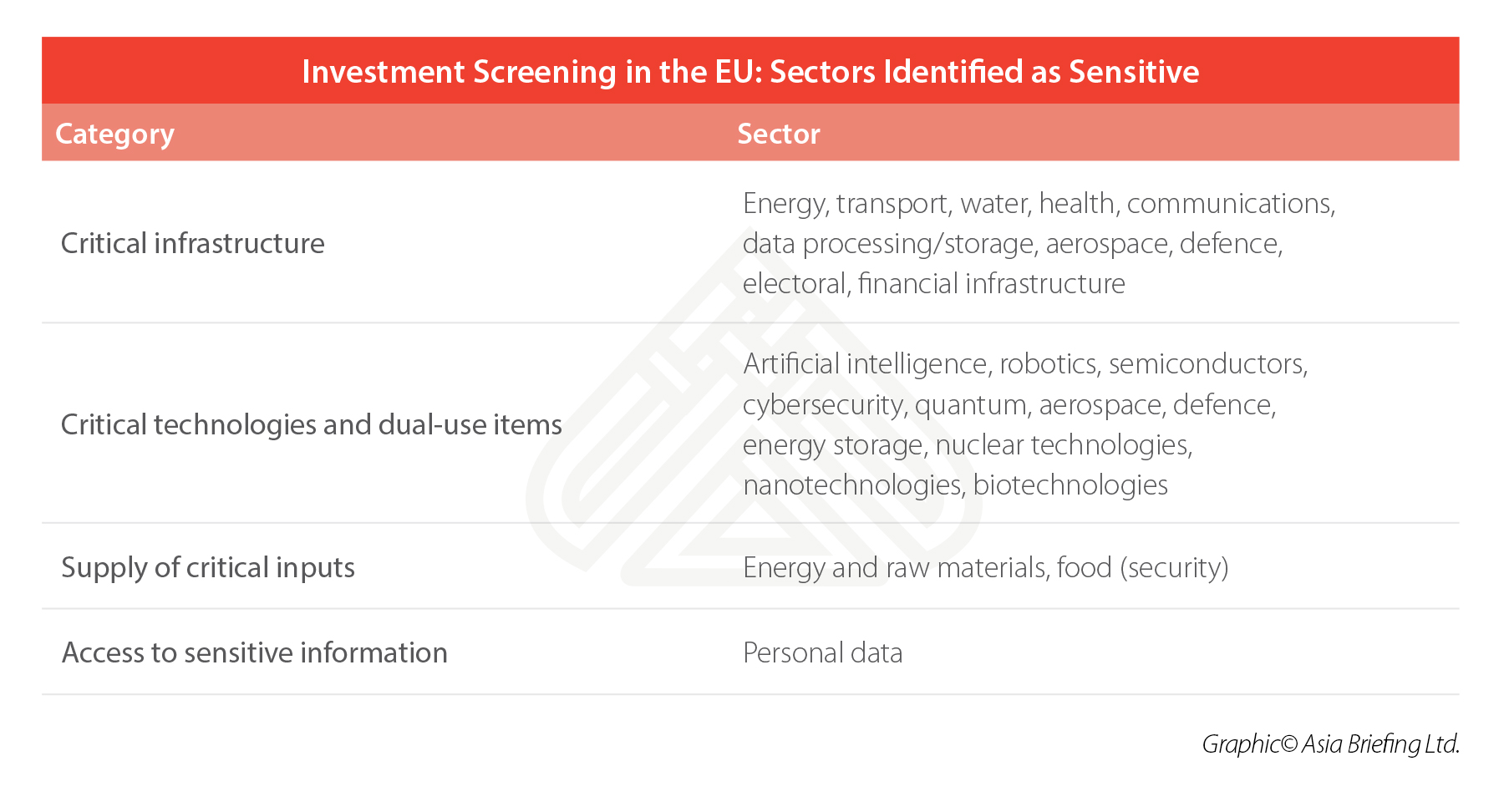

Investment screening in the EU does not discriminate based on the country of origin, but looks at investments based on three main categories:

- Investments in sectors considered sensitive;

- Investments by state-controlled entities; and

- Investments in accordance with state-led outward projects.

The sectors that are deemed sensitive depends on the individual member country and the screening policy it employs.

Sectors considered to be essential to the running of a developed economy are often categorized as sensitive.

The recently introduced EU-wide screening coordination policy identifies the following sectors as sensitive areas:

Impact of screening policies on Chinese investment

Investments by state-controlled entities are viewed with caution in the EU because of the potential for foreign governments to use their control of certain assets as leverage in foreign affairs issues.

For Chinese firms, this not only includes state-owned enterprises (SOEs), but also some private companies who might have links to the Chinese government.

Investments in accordance with state-led outward projects – for example, China’s ‘Made in China 2025’ plan, which aims to make China a leader in a range of high-technology goods – are also viewed with suspicion for the same reason.

Investments with state-led direction into targeted sectors may be used by foreign governments to gain international strategic advantages. It also has implications for risks to intellectual property – an issue that is currently at the heart of the US-China trade war.

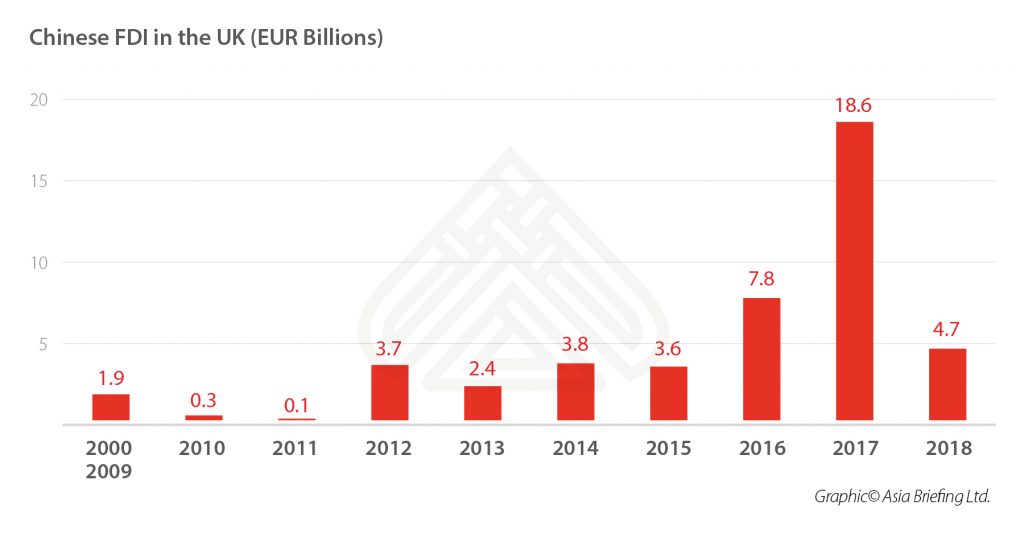

China’s FDI into the UK

Significant mainland Chinese investment into the UK started in around 2003 when Chinese FDI stood at an average of EUR 255 million (US$254 million) per year until 2011. From 2012, investment flows have become more substantial, averaging EUR 4.3 billion (US$4.9 billion) over the next five years.

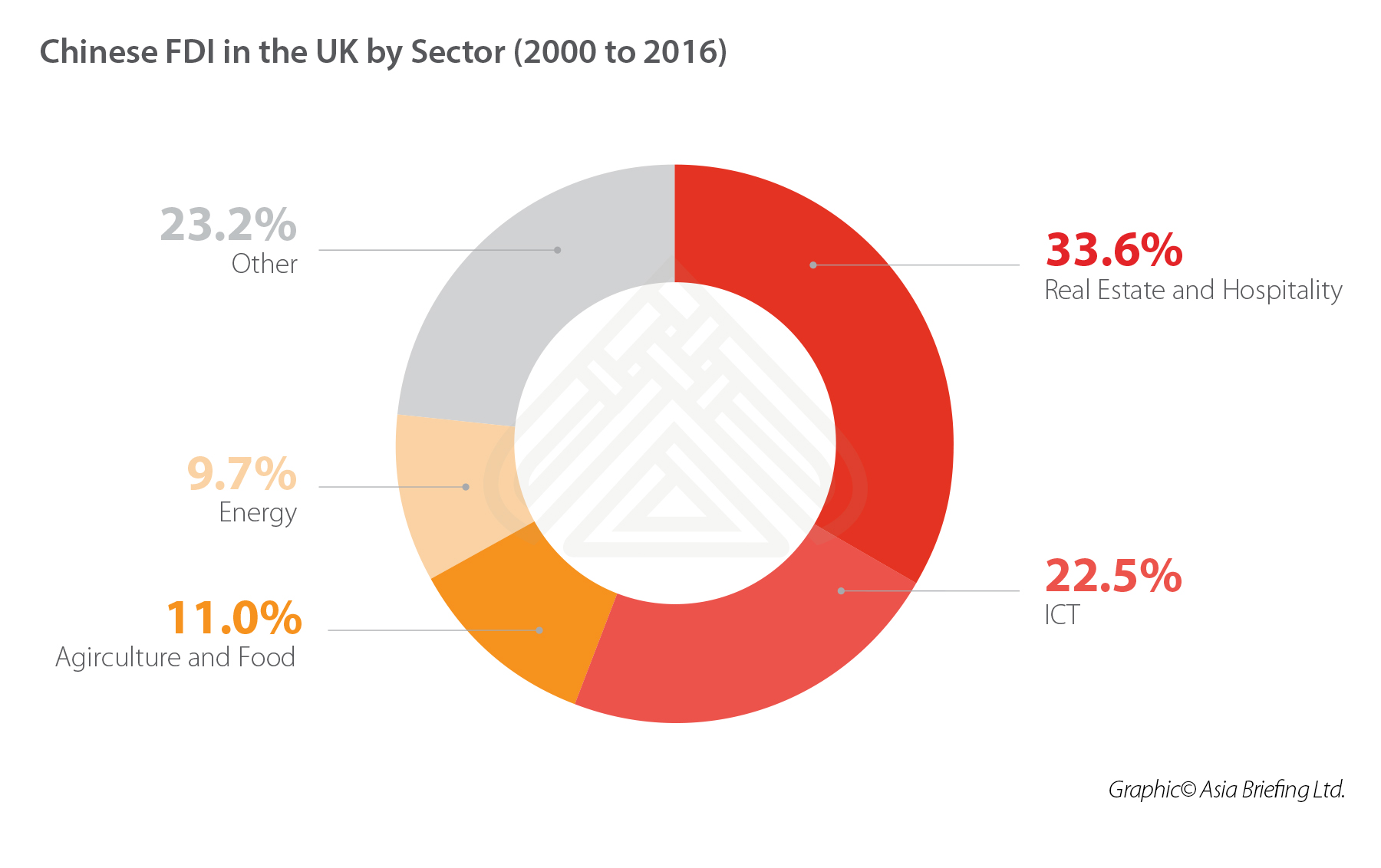

Investment in areas considered sensitive in the UK have mainly been concentrated in information and communication technology (ICT) and energy. 22.5 percent of all Chinese investment from 2000-2016 was in the ICT sector and 9.7 percent was in energy.

UK suspicion of Chinese investment in the energy sector actually led the government to delay plans to build the Hinkley Point C nuclear plant because of security concerns over a Chinese company’s 30 percent stake in the deal.

Chinese SOEs have played a big role in Chinese FDI to the UK. The large increase in 2017 FDI was due to China’s sovereign wealth fund, China Investment Corporation (CIC), making a massive EUR 12.5 billion (US$14.1 billion) purchase of the warehouse company Logicor.

Screening policy changes

Although the UK already had a reasonably strong screening system, changes were made in 2018. The two tests that allow the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to review FDI – the turnover test and the share of supply test – were both amended.

The CMA can now review transactions in sensitive sectors worth GBP 1 million (US$1.3 million). This is quite a significant change as the previous threshold for review was GBP 70 million (US$92 million).

The share of supply test evaluates transactions based on whether foreign companies will control too much of the market. A transaction can now be reviewed if the target company for investment alone supplies 25 percent or more of a good in a sensitive sector.

Key sensitive sectors in the UK include quantum computing, computer hardware, and software as these sectors perform a crucial role in the country’s economic development and contribute to national security.

China’s FDI into Germany

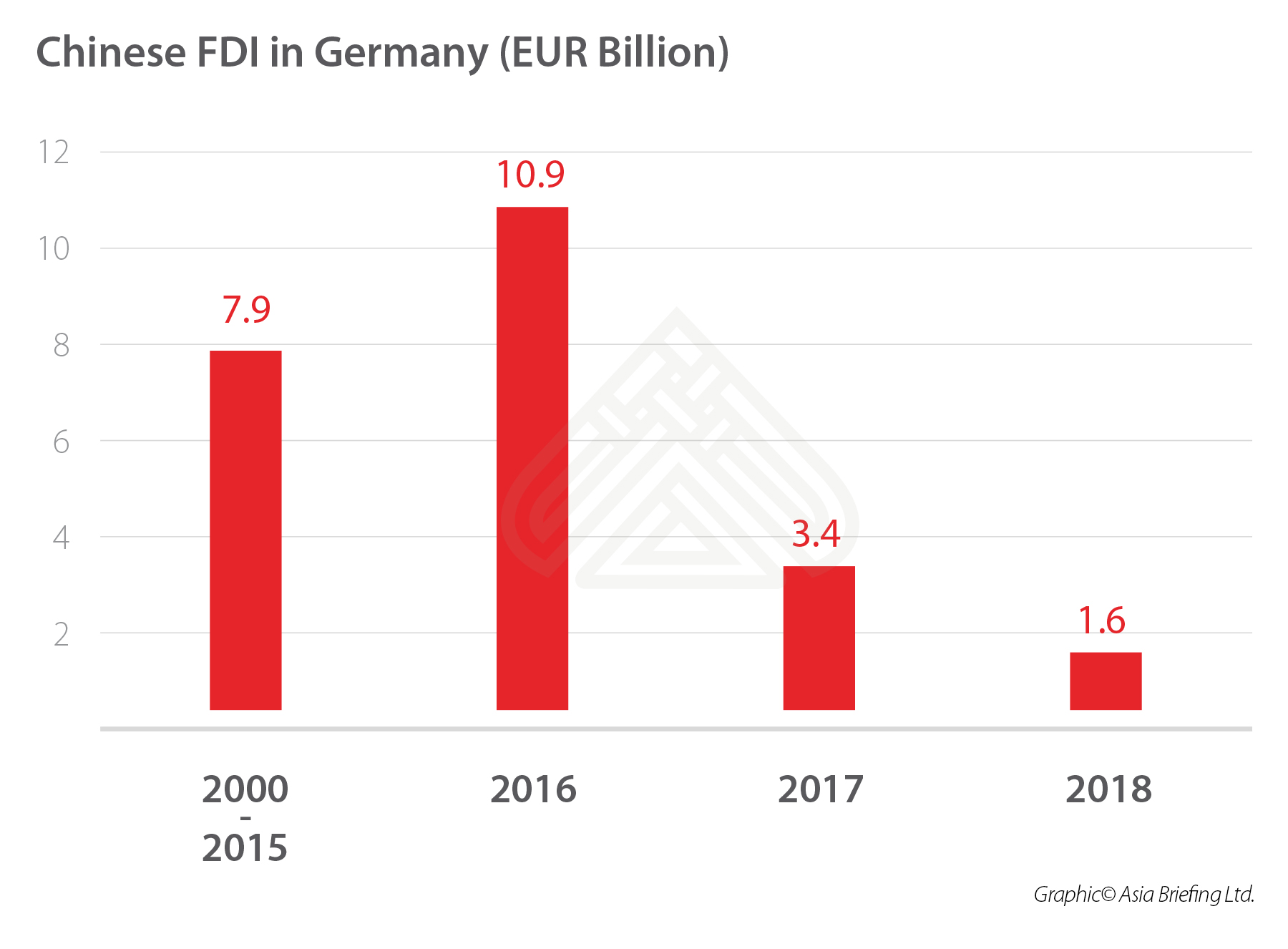

Beginning in 2011, Chinese FDI levels in Germany stood around EUR 1 to 2 billion per year (US$1.3 to 2.6 billion).

In 2016, FDI shot up to EUR 10.9 billion (US$21.3 billion). This essentially represented a catch-up for Germany as a target for Chinese investment.

Much of the core investment activity has been made by private companies, but that hasn’t diminished suspicion. The 4.6 billion (US$5.2 billion) takeover of KUKA, a robotics company, by the private Chinese firm Midea in 2016 drew the German public’s attention to the perceived potential risks of Chinese FDI.

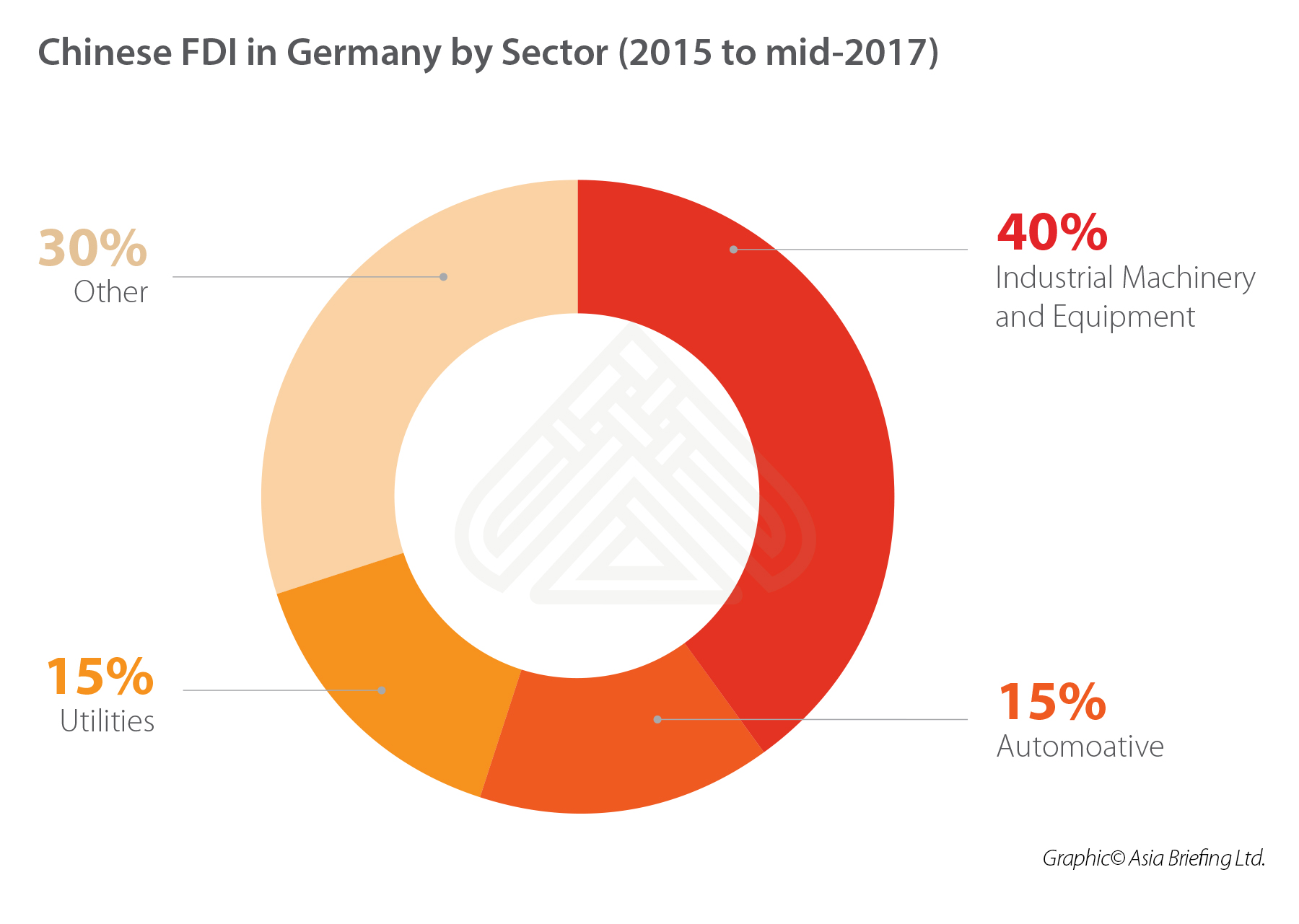

This suspicion can partly be understood by the overwhelming activity by Chinese investors in Germany’s advanced manufacturing sector.

The Chinese government has been pushing Chinese firms to acquire technological know-how from abroad, and Germany’s manufacturing sector is considered a major target.

From 2015 to mid-2017, industrial machinery and equipment took about 40 percent of all Chinese investment in the country. Next in line were both the automotive industry and the utilities industry, which took about 15 percent of total Chinese FDI, respectively.

In 2018, the German government ostensibly blocked two Chinese investment transactions from occurring: one in 50hertz, which runs a high-voltage transmission grid and another in Leifeld Metal Spinning, which creates high-strength materials for the aerospace and nuclear industries.

Screening policy changes

Before 2018, the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) could only block investment transactions of stakes worth 25 percent or more in the target company.

After the state-owned development bank had to buy a 20 percent stake in 50hertz to stop Chinese investors from doing so, the regulations were changed so that the BMWi can now block any non-European firm planning to buy more than a 10 percent stake in sensitive sectors.

Sectors considered sensitive in Germany include IT security, an array of software and computer technology, energy, telecommunications, transport, healthcare, water, food, finance, and insurance. For all other sectors, the 25 percent stake threshold remains.

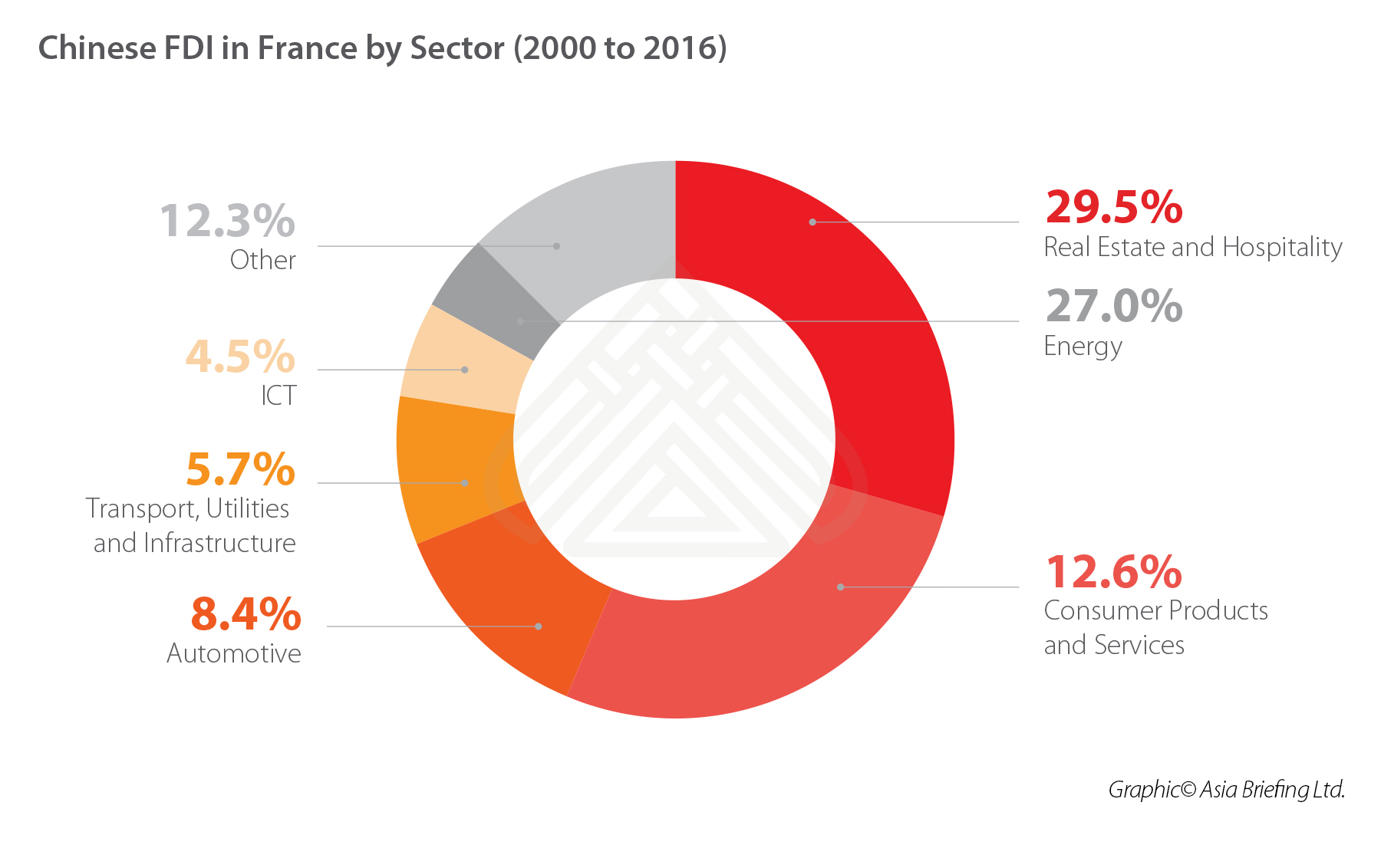

China’s FDI into France

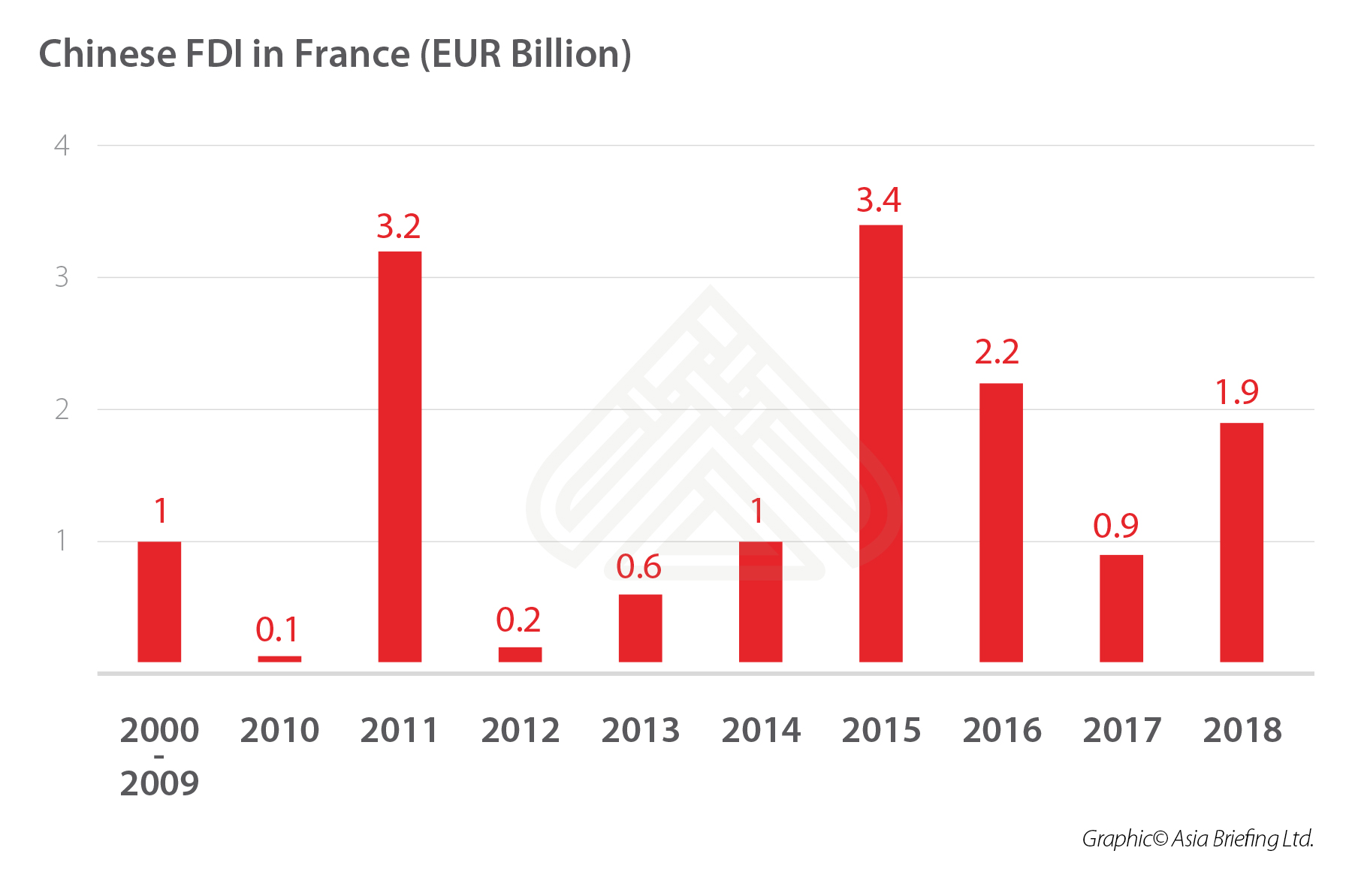

From 2000 to 2010, outbound Chinese FDI to France was quite low, averaging at EUR 87.9 million (US$99.4 million) per year. However, in 2011 there was a large increase, which then set the scene for the next seven years where average Chinese FDI into France was EUR 1.7 billion (US$1.9 billion).

The French have seen a large amount of Chinese investment in the energy sector. From 2000-2016, 27 percent of all investment was in the energy sector. Investment from the CIC has also played a large role in this.

In 2011, it acquired a 30 percent stake in the exploration and production division of GDP Suez (now Engie), one of the world’s largest gas and electricity companies.

In the technology sector, the CIC made a EUR 385 million (US$435 million) investment in the satellite company Eutelsat in 2012. And in 2016, a deal was signed with the Chinese sovereign fund to develop an investment fund for infrastructure projects in Paris.

Screening policy changes

In general, FDI in France is not subject to review. Investments in sensitive sectors, however, are subject to an automatic screening process. These sectors include energy, water, transportation, telecommunications, healthcare, and defense.

In 2018, the French further expanded the set of sensitive sectors in which FDI will be subject to review. Additional target sectors are cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, and space operations.

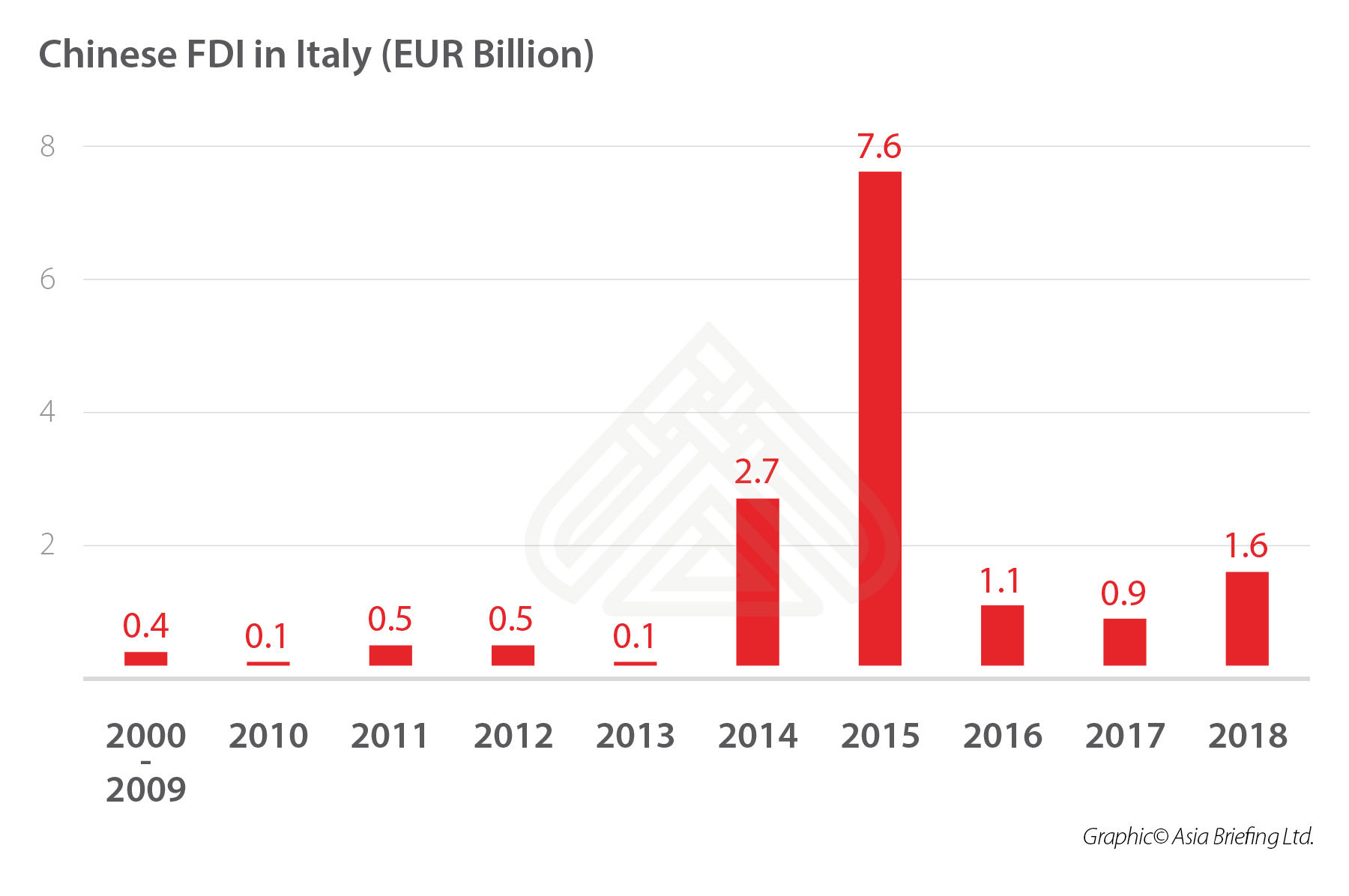

China’s FDI into Italy

Although Germany, France, and the UK have traditionally been the preferred destinations for Chinese FDI, in 2015, Italy overtook France for cumulative Chinese FDI beginning from the year 2000.

The sudden increase in the 2015 FDI flow was due to the Chinese SOE ChemChina acquiring 16.89 percent of Pirelli, the world’s fifth largest tire maker, for EUR 7 billion (US$7.9 billion).

Chinese FDI spans across a wide variety of industries in Italy, including entertainment, robotics, and luxury brands. The People’s Bank of China has invested around two percent in 10 of Italy’s largest companies, including those in the automotive industry and telecommunications, amounting to a total of about EUR 3.5 billion (US$ 4 billion).

Energy, once again, is a key investment target. In 2014, China’s State Grid acquired a 35 percent stake for EUR 2.1 billion (US$2.4 billion) in the energy grid company CDP Reti.

Italy signs Belt and Road MoU with China

Before the change of government in 2018, Italy’s cabinet passed a degree allowing for greater disclosure requirements for FDI transactions and expanded its capacity to veto transactions in a greater number of sectors, including data storage and processing, artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, dual-use technology, and nuclear technology.

The government, however, changed hands when the anti-establishment Five Star Movement won the most votes in the 2018 election. The coalition that now occupies Italy’s government is considerably more anti-European Union and more pro-China.

In March 2019, Italy became the first large Western economy to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – an infrastructure program to connect the trade routes of Asia with Africa and Europe. This move drew a large amount of criticism from large EU and non-EU states who claim the BRI is a Chinese strategy to buy influence around the globe.

Although no changes have been made to Italy’s screening policy since the signing, the government has indicated that it will be open to investment in sectors that other EU states would perhaps be more uncomfortable with.

The level of Chinese investment in the EU is dependent on the state of the Chinese economy and the level of control that the Chinese government puts on capital outflows. Nevertheless, the MoU will likely provide a boost to Italy’s share of Chinese FDI, especially when increased investment controls – particularly in Germany – decrease the investment attractiveness of the other large EU economies.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia from offices across the world, including in Dalian, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Readers may write to china@dezshira.com for more support on doing business in China.

- Previous Article China Delays Cross-Border Data Transfer Rules amid Trade War Talks

- Next Article Traveling in China – Business Etiquette and Culture