Debt in China and Its Implications for the Private Sector

By Harry Handley

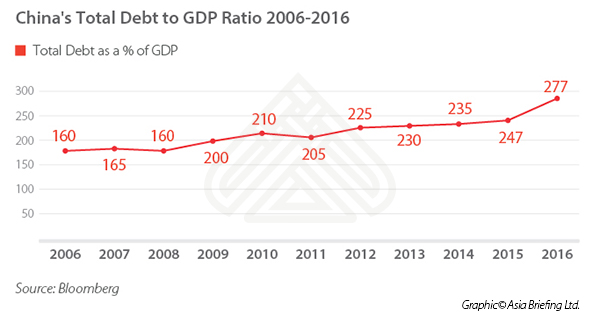

China’s debt is reaching an unprecedented level; as a percentage of GDP, debt is at its highest ever level, and is expected to continue rising. The current debt situation shares worrying similarities with the conditions seen in the US, Japan, and Thailand before their respective financial crises.

At the beginning of April, S&P Global Ratings cut the credit rating of Jiangsu New Headline Development Group, a local government funding vehicle (LGFV) owned by Lianyungang City in Jiangsu province. This is the first instance of a downgrade for an LGFV, a financial institution used by local governments to procure credit for public investment projects.

LGFVs are just one link in a complex chain of rising debt that embroils China’s public sector. Here, we examine key aspects of debt in China and how it can affect the private sector.

What is China’s debt situation?

In order to avoid the wrath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, in November of that year China unveiled its largest fiscal stimulus package in history. RMB 4 trillion (US$580 billion) was injected into various sectors of the economy using state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the state-owned banks as fiscal instruments. Over the following years, debt continued to rise but growth began to slow; the amount of debt required to add RMB 1 to GDP increased from RMB 1 in 2008 to around RMB 4 today.

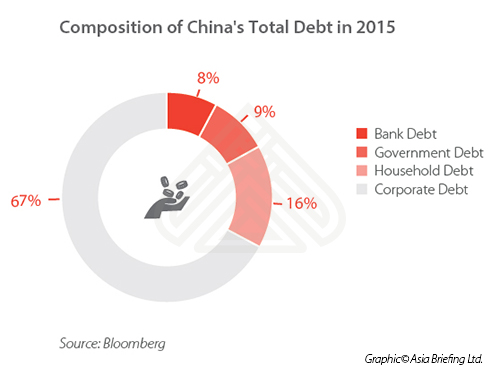

China’s debt to GDP ratio reached between 240 and 277 percent, varying by source, at the end of 2016. Two thirds of this debt is corporate debt, which includes the aforementioned LGFVs, SOEs, and private sector companies. The debt of LGFVs can only be estimated, and may be much higher in reality due to the use of ‘shadow banking systems’ and a lack of transparency in accounting standards.

The debt situation is a multifaceted web of bank loans, corporate bonds, and mutual guarantees between enterprises. It is these mutual guarantees – often excluded from balance sheets – and other unregulated shadow banking systems that mask the real level of leverage in the market and increase the risk of failure and effect on the economy.

The World Economic Forum reported that SOEs and LGFVs are often re-lending cheaply obtained credit at higher rates. A consequence of this is an increase in bad debt and non-performing loans. According to media reports, bad debt in China’s commercial banks stands at RMB 1.5 trillion (US$220 billion). However, experts suggest this figure may be up to 14 times higher due to attempts to conceal the true extent of the problem by lenders and their government affiliated borrowers.

How is the private sector involved?

A third of all corporate debt belongs to private enterprises, derived from bank loans, bond offerings, and shadow banking activities. In addition, some private companies have off-the-books agreements with their counterparts to guarantee loans. With many companies having multiple agreements, this creates a chain of debt, significantly increasing each player’s exposure to the debt that has developed.

The case of Qixing Group Co. illustrates how the private sector is involved in the debt problem. Qixing Group Co. was China’s largest privately owned aluminum smelting company, based in Shandong province.

Taking advantage of the government’s financial crisis stimulus, as well as close ties with local governments and banks, Qixing used cheap and readily available credit to expand its aluminum business and venture into areas such as property development and power cables. The company even opened a five star hotel.

Over the years, the company’s borrowing from financial institutions exceeded RMB 7 billion (US$1 billion); it is estimated that a further RMB 4 billion (US$580 million) was borrowed from private lenders. A large amount of this debt was secured using ‘mutual guarantee’ agreements with other companies, which is a somewhat common practice in China.

![]() RELATED: Pre-Investment and Entry Strategy Advisory from Dezan Shira & Associates

RELATED: Pre-Investment and Entry Strategy Advisory from Dezan Shira & Associates

But Qixing ran out of money in March 2017. According to media reports, the group was under ‘trusteeship’, signaling the local government’s lack of faith in the current owners to stabilize Qixing and save it from collapse.

Xiwang, who guaranteed around RMB 2.9 billion of Qixing’s debt, saw their share price fall by almost 15 percent following the news of Qixing’s demise. According to Bloomberg, this debt guarantee amounts to around 17 percent of Xiwang’s equity.

Should lenders call in Qixing’s outstanding debt, this could also see the fall of Xiwang and set off a chain reaction with other ‘mutual guarantee’ agreements coming under strain. Investors also dumped corporate bonds from lenders in the same region as Qixing and Xiwang, again signaling the collateral danger of the situation.

This example highlights that it is not only the indebted companies that are at risk from the current situation. It is also the sequence of companies that have acted as guarantors to loans and left such agreements off their balance sheets, thus avoiding scrutiny from auditors, regulators, and future lenders. Further, seemingly unassociated companies in proximity to the struggling companies can also be dragged into the mess through bond and share sell offs. This demonstrates the far-reaching ramifications of even a single loan default.

What is the government doing?

At the recent Two Sessions meetings in March, SOE reform and higher regulation of the finance industry were high on the agenda. Since then, the government has already taken a number of steps to regulate financial institutions and borrowers. Guo Shuqing was appointed Chairman of the China Banking Regulatory Commission in late February to lead this effort.

Regulators have increased reporting requirements in order to deleverage the shadow banking sector and increase transparency amongst investors and debtors. The People’s Bank of China has also increased interest rates twice so far in 2017 in an attempt to deter borrowers.

China’s state influence over the banking sector and large segments of the economy put it in a strong position to continue to ease the pressure. Many analysts suggest that the government may eventually absorb debt owed by SOEs to state-owned banks as a part of its ‘social welfare expenditures’. The issue of debt-to-equity swaps by state-owned banks is also a potential method of reducing leverage in the economy.

However, China’s regulatory tightening has already led to diminished confidence in the country’s equity and debt markets, and have caused global commodity prices to tumble. In April, China experienced its weakest manufacturing growth in seven months, and its lowest service growth in 11 months.

Despite April’s slower growth – which came on the heels of a stronger than expected first quarter – observers expect regulation to continue to intensify. The Chinese government is seeking to minimize structural risks and reduce the potential for an unexpected economic shock ahead of the fall’s politically sensitive 19th Party Congress. Nevertheless, if the economy continues to slow, a pause in regulatory tightening could be an option for Beijing to meet its annual growth target in a politically important year.

![]() RELATED: Why People Don’t Trust China’s Official Statistics

RELATED: Why People Don’t Trust China’s Official Statistics

What does it mean for your business?

In any event, a squeeze on the credit available to private enterprises is likely. Difficulties in fundraising will prove a challenge to the growth of enterprises, which may instead have to turn to equity funding and capital markets for funding.

However, the crippling debt of a large number of SOEs may reduce their power and dominance, leveling the playing field for private enterprises that are more efficiently leveraged and managed. This debt crisis will likely prove a catalyst for further reform; growth in the private sector would help to prevent this debt crisis from becoming a full-blown economic crisis.

It does not appear that foreign firms in China have been caught up in the spiraling debts in the Chinese market. However, what is clear is that the fallout from this debt crisis, if allowed to run its course, will have an impact on the whole economy. Whether it will be a financial liquidity crisis, a significant drop in the rate of economic growth, or both, all firms with interests in China must now conduct due diligence on their partners and monitor the regulatory environment to gauge how the debt problem will manifest.

|

China Briefing is published by Asia Briefing, a subsidiary of Dezan Shira & Associates. We produce material for foreign investors throughout Asia, including ASEAN, India, Indonesia, Russia, the Silk Road, and Vietnam. For editorial matters please contact us here, and for a complimentary subscription to our products, please click here. Dezan Shira & Associates is a full service practice in China, providing business intelligence, due diligence, legal, tax, IT, HR, payroll, and advisory services throughout the China and Asian region. For assistance with China business issues or investments into China, please contact us at china@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com

|

Dezan Shira & Associates Brochure

Dezan Shira & Associates is a pan-Asia, multi-disciplinary professional services firm, providing legal, tax and operational advisory to international corporate investors. Operational throughout China, ASEAN and India, our mission is to guide foreign companies through Asia’s complex regulatory environment and assist them with all aspects of establishing, maintaining and growing their business operations in the region. This brochure provides an overview of the services and expertise Dezan Shira & Associates can provide.

An Introduction to Doing Business in China 2017

This Dezan Shira & Associates 2017 China guide provides a comprehensive background and details of all aspects of setting up and operating an American business in China, including due diligence and compliance issues, IP protection, corporate establishment options, calculating tax liabilities, as well as discussing on-going operational issues such as managing bookkeeping, accounts, banking, HR, Payroll, annual license renewals, audit, FCPA compliance and consolidation with US standards and Head Office reporting.

Payroll Processing in China: Challenges and Solutions

In this issue of China Briefing magazine, we lay out the challenges presented by China’s payroll landscape, including its peculiar Dang An and Hu Kou systems. We then explore how companies of all sizes are leveraging IT-enabled solutions to meet their HR and payroll needs, and why outsourcing payroll is the answer for certain company structures. Finally, we consider the potential for China to emerge as Asia’s premier payroll processing center.

- Previous Article Shanghai Revises Minimum Wage, Social Insurance Contribution Rates

- Next Article China to Develop Track Changing Trains to Handle Different OBOR Gauges