Investing in China’s Education Industry – Part 1

By Dezan Shira & Associates

Editor: Zhou Qian

The following is the first of a two-part article taken from our August magazine, China Investment Roadmap: the Education Sector. The second part can be found here.

Despite China’s promise to gradually open up its education sector to the world following its accession to the WTO in 2001, the country’s education industry is still a highly sensitive area for foreign investment. This is mainly due to how closely intertwined it is with Chinese ideology and identity and its propensity to influence children’s beliefs, resulting in foreign investors engaging in education in China usually being faced with closer scrutiny.

Market Entry Policies

According to China’s Catalogue of Industries for Guiding Foreign Investment (2015), the education industry is divided into three separate categories. While compulsory education institutions (primary and middle schools) and special training institutions (such as military, police, political, and Chinese Communist Party schools) are still considered prohibited areas, foreign investors are allowed to invest in pre-school educational institutions, high schools, and tertiary educational institutions in the form of Sino-foreign joint ventures, in which foreign majority ownership is allowed but only when the Chinese party is in a leading position. That is to say, the principal or key administration officer in such institutions is required to be a Chinese national and the council, the board of directors, or joint administration committee of the school must be majority Chinese.

RELATED: Pre-Investment and Entry Strategy Advisory

RELATED: Pre-Investment and Entry Strategy Advisory

In contrast to these restrictions, foreign investors are encouraged to invest in sports training and non-academic vocational training institutes (such as IT, accounting, English, etc.), primarily because these industries are considered to have talent shortages.

The only way for foreign investors to circumvent the restrictions listed in the Catalogue is to establish international schools for the children of foreigners. According to the Interim Provisions on Set-up of Schools for Children of Foreign Nationals in China, qualified foreign organizations, enterprises, and individuals legally residing in China are allowed to establish wholly foreign owned and controlled pre-schools and K12 schools that are only open to the children of foreign nationals. However, it’s important to note that this kind of international school is forbidden to have any branches – it can only be a single school.

Non-profit or For-profit

Another acute consideration for foreign investment in China’s education industry is whether foreign parties can profit from their investment. In China, education is traditionally regarded as a public cause, and the government has therefore been reluctant to privatize the sector. As such, China’s laws and regulations usually require education institutions to be non-profit organizations, but there are several holes and contradictions across different pieces of legislation. Article 28 of the Implementation Measures on Establishment and Operation of Sino-Foreign Cooperative Educational Institutions specifies that all Sino-foreign cooperative educational institutions are prohibited from for-profit activities.

This also applies to the aforementioned international schools for children of foreigners. Correspondingly, education institutions are usually required to be registered as “private non-enterprise units” in the civil affairs department, rather than registered as “limited liability companies” in the Administration of Industry and Commerce (AIC).

Although the Private Education Promotion Law stipulates that investors could get a “reasonable return” of up to 75 percent of the net margin from a private education institutions, it is still significantly different from regular dividends distribution. In practice, “reasonable return” is rarely added into the institution’s Articles of Association because this concept is never clearly defined, making pre-establishment approval even more difficult as a result.

Nevertheless, the recent revision of China’s national education laws in 2015 – together with some local level regulations and practices – sheds some light on the feasibility of for-profit education. The revised PRC Education Law abolished the previous provision “No organization or individual may establish or run a school or any other educational institution for profit-making purposes”, pointing towards a more relaxed attitude from the government regarding for-profit education. At the local level, Shanghai released two provisional regulations on commercial training institutions in 2013, making Sino-foreign for-profit education explicitly operable in the Pilot Free Trade Zone (FTZ). Similar practices are also observed in Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hangzhou, amongst others, though these cities have not released formal regulations as Shanghai has. Conversely, however, the vote on the proposed amendment to the “Private Education Promotion Law”, which emphasizes the legitimacy of for-profit education and specifies the transfer method of non-profit education institutions to for-profit institutions, was temporarily suspended. There are also further contradictions in China’s recently released NGO law, which is discussed in detail in this magazine’s final article. Consequently, it is still too early to say that the barriers to for-profit education have been eliminated, both legally and in practice.

Common Investment Models

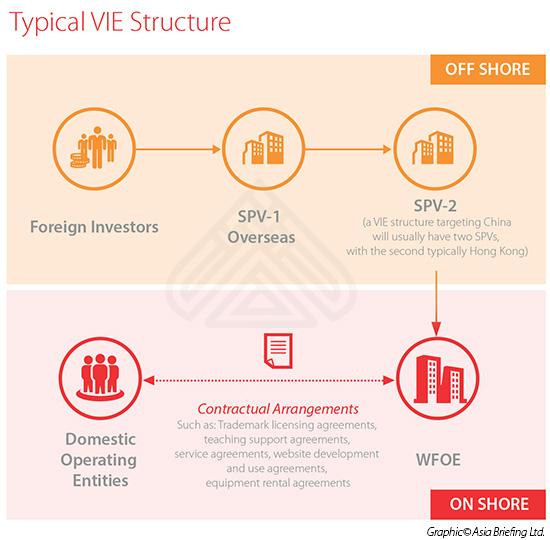

In view of the abovementioned restrictions and market entry barriers, foreign investors sometimes use the “variable interest entities (VIE)” model to access China’s education industry. Under this model, foreign investors retain control over entities operating domestically in China through a series of contractual arrangements rather than direct shareholding. Typical examples include TAL Education Group, New Oriental, and Maple Leaf Educational System, the structure of which is summarized in the graph in the upper left.

However, considering the increasing legal risks embedded in the VIE structure, such as contract invalidity, fighting of control rights, and transfer pricing reviews, investors may instead choose one of several direct investment models, including:

- Model 1: Set up self-owned pre- and K12 international schools for children of foreigners or vocational training centers, e.g. Wellington College International Shanghai, Wall Street English, etc.

- Model 2: Set up Sino-foreign cooperative educational institutes, such as a university-level cooperation (e.g. NYU Shanghai), department-level cooperation (e.g. China-EU School of Law), and program-level cooperation (MDS Program between Peking University and Hong Kong University)

- Model 3: Franchising, focusing on pre-school and English training, e.g. EF Education and My Gym (early childhood development programs)

- Model 4: M&A—such as Sequoia Capital’s investment in Universal Education Group

This article is an excerpt from the August issue of China Briefing Magazine, titled “China Investment Roadmap: the Education Sector.” In this issue of China Briefing, we navigate through China’s regulatory framework for investment into education, presenting a roadmap for best practices in the industry. We examine the key market information that has driven the industry’s growth, analyze the different investment models that are available for foreign companies, and finally discuss the effect that China’s recently released NGO law will have on foreign investment into education. This article is an excerpt from the August issue of China Briefing Magazine, titled “China Investment Roadmap: the Education Sector.” In this issue of China Briefing, we navigate through China’s regulatory framework for investment into education, presenting a roadmap for best practices in the industry. We examine the key market information that has driven the industry’s growth, analyze the different investment models that are available for foreign companies, and finally discuss the effect that China’s recently released NGO law will have on foreign investment into education. |

Establishing & Operating a Business in China 2016

Establishing & Operating a Business in China 2016

Establishing & Operating a Business in China 2016, produced in collaboration with the experts at Dezan Shira & Associates, explores the establishment procedures and related considerations of the Representative Office (RO), and two types of Limited Liability Companies: the Wholly Foreign-owned Enterprise (WFOE) and the Sino-foreign Joint Venture (JV). The guide also includes issues specific to Hong Kong and Singapore holding companies, and details how foreign investors can close a foreign-invested enterprise smoothly in China.

China Investment Roadmap: the Commercial Real Estate Sector

China Investment Roadmap: the Commercial Real Estate Sector

In this issue of China Briefing, we explore the latest trends in commercial real estate in China, and discuss how foreign companies can benefit from China’s massive construction boom. We provide a guide to how firms can sell construction materials in China, and finally detail how foreign architects can most effectively enter and take advantage of China’s rapid urbanization.

China Investment Roadmap: The Entertainment Industry

In this special edition China Briefing Industry Report, we cast our gaze over the broad landscape of China’s entertainment industry, identifying where the greatest opportunities are to be found and why. Next, we detail some of the most important issues for foreign investors to be aware of, including legal, regulatory, and tax considerations specific to the industry. Lastly, we provide an insider analysis of the sector’s unique HR & payroll challenges.

- Previous Article Resolving Labor Conflicts: New Regulations on Wage Payment Methods in Shanghai

- Next Article Sketching Opportunities in China’s Cartoon and Animation Industry