US, China Sign Phase One Trade Deal: How to Read the Agreement

By Dorcas Wong, Melissa Cyrill, and Zoey Zhang

On January 15, 2020, the US and China signed the much-anticipated phase one trade deal (US-China Economic and Trade Agreement) in Washington DC. The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) and the Ministry of Commerce of China (MOFCOM) later released the full text of the deal in English and Chinese.

This initial trade deal is perceived as the first sign of de-escalation in the protracted US-China trade war. Now going over 18 months, it has witnessed the world’s two biggest economies battle crises followed by back-and-forth negotiations week-on-week – not to mention a tit-for-tat tariff war, introduction of foreign technology restrictions, and cases being fought at the WTO.

While hailed as ‘historic’ by those signing it – hyperbolic for its modest aims – what the deal hopes to be is enforceable. Its provisions puts into immediate effect tariff rollbacks, expansion of trade purchases, and renewed commitments on intellectual property (IP) rights, technology transfer, and currency practices, among others.

During the signing ceremony at the White House, US President Donald Trump touted the deal as “a momentous step, one that has never been taken before with China toward a future of fair and reciprocal trade with China.” Chinese Vice President Liu He, in turn, delivered a message from the Chinese President Xi Jinping, who praised the trade deal as a sign that the two countries could resolve their differences with dialogue.

The mood as a result has been a mixture of relief after subsequent rounds of talks and consultations left all sides weary and businesses unsettled or facing losses. The most important aspect of getting some sort of deal signed has therefore been a sense of deliverance from further stalemate or prolonged uncertainty, and a sense of moving forward towards more constructive changes in the ways both countries do business, including with each other.

Not surprisingly then, the agreement leaves many deeply rooted issues unresolved. Prominent among them is China’s position on industrial subsidies. Further, while the December 15 tariffs have been suspended, the previous tariffs remain despite some rollback.

These grievances will be taken up in time – determined by whether the Trump administration considers it to be in its best interests in an election year. China knows this and will want to slow down any future talks lest it expose itself to more visible compromise. The two sides have sold the deal in their own language – the US turning up the volume on Chinese monetary commitments to purchase US$200 billion worth of US imports while China has stated that these will conform to market requirements and WTO conditions. The dual interpretation leaves ample space for future disputes.

Nevertheless, last week, the two countries announced they would be resuming their twice yearly talks on trade and economic issues, which were a convention under previous US presidents. While the Trump White House opted for a more confrontational and punitive approach that led to the trade war, a return to old consultative ways might be necessary to rebuild the damaged bilateral relationship and shore up on much depleted trust reserves.

Parallel to the noise generated by this phase one deal – trade envoys from US, Japan, and the European Union met on January 14, and announced a proposal to strengthen the WTO’s provisions on industrial subsidies, which they found to be “insufficient to tackle market and trade distorting subsidization existing in certain jurisdictions,” a barely veiled reference to China.

How this impacts future trade discussions with China remains to be seen but one can expect that the new status quo is here to stay – one that will likely see China face some tough situations with old trade partners.

This might drive Beijing to invest more diligently on expanding new trade relationships, including those along the Belt and Road and with the Eurasian Economic Union. But narrative and projections aside, let’s get into what the US-China Economic and Trade Agreement actually says.

WEBINAR: August 26, 2020

We discuss the Hong Kong National Security Law and its impact on US businesses.

REGISTER TODAY

What’s in the phase one trade deal

The 96-page agreement consists of eight chapters on intellectual property rights, technology transfer, food and agricultural products, financial services, foreign exchange regulation, trade expansion, dispute resolution, and final provisions. It covers the main subjects of the Section 301 investigation launched by the USTR against China in 2017. Below we provide a reading of key provisions in the agreement.

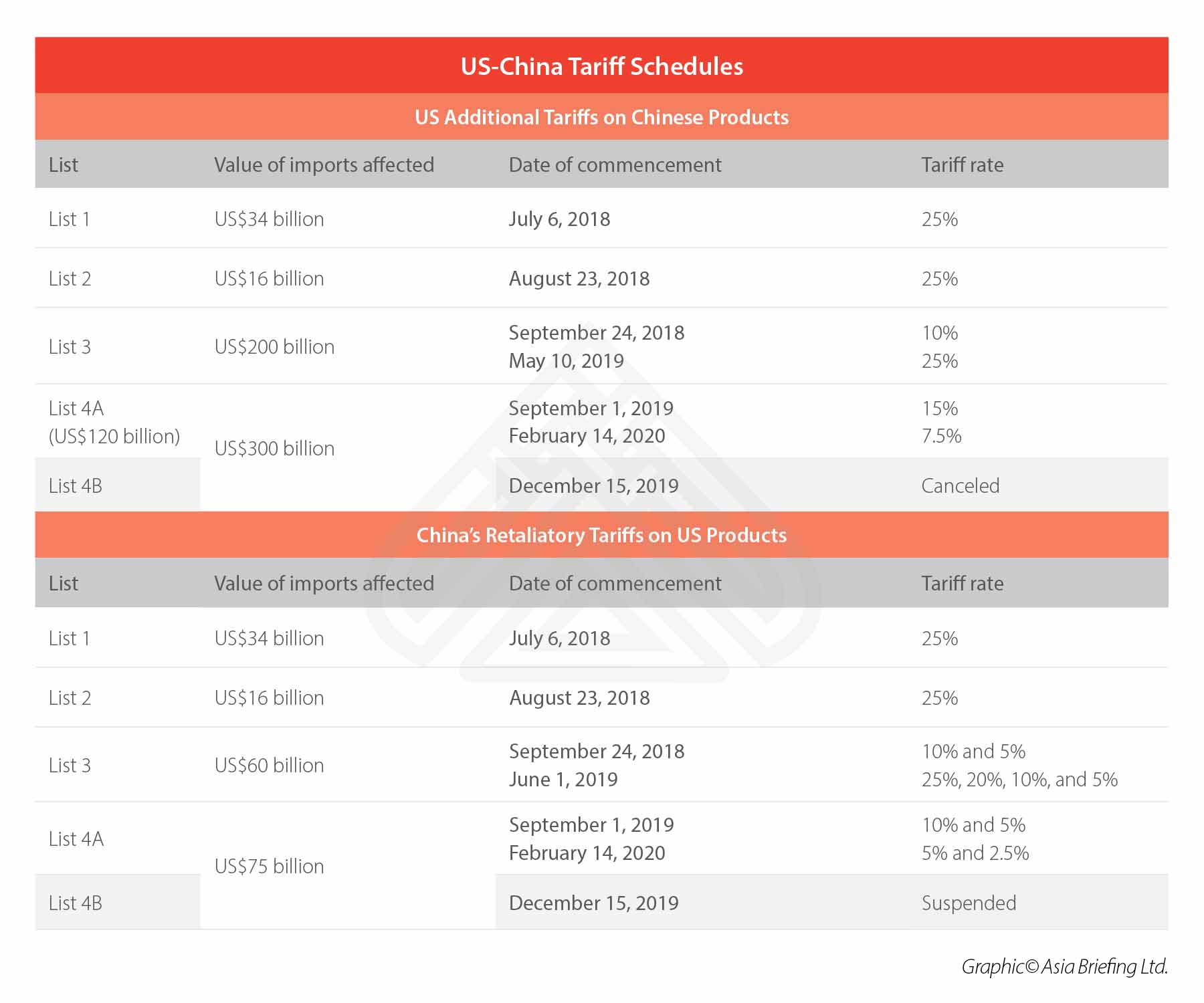

Tariff rollback

The deal cancels the tariffs originally set to take effect on December 15, 2019 that would have affected mass consumed Chinese-made imports like cellphones, toys, and laptops, among others. In addition, it reaffirms Trump’s commitment to halve the September 1, 2019 tariff from 15 percent to 7.5 percent on US$120 billion worth of Chinese products, including flat-panel televisions, bluetooth headphones, and footwear. However, other tariffs will remain. These include the 25 percent US tariffs slapped on US$250 billion worth of Chinese products and China’s retaliatory tariffs on US$110 billion of US goods. According to US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, more tariffs will be rolled back in the phase two trade deal, which was brought up at the close of the phase one deal. A summary of the tariffs implemented by both countries can be found in the table below.

Expanding trade and services (Chapter 6)

A centerpiece of the deal is China’s pledge to purchase a minimum of US$200 billion worth of additional US goods and services over the next two years. The additional US$200 billion in purchases include:

- US$77.7 billion of manufactured goods;

- US$32 billion of agricultural goods;

- US$52.4 billion of energy goods; and

- US$37.9 billion of services.

The table below provides a summary of China’s schedule of increased purchases from 2020 to 2021.

Special focus appears to be placed on agricultural and financial service imports, both of which formed their own chapters within the agreement. The agricultural provisions support the expansion of US agricultural exports, particularly seafood products, poultry rice, dairy, infant formula, horticultural products, animal feed and additives, pet food, and agricultural biotechnology.

Overall, combining a baseline of US$186 billion purchases in 2017 with the increased US$200 billion purchases, US exports to China should in theory climb to US$263 billion in 2020 and to US$309 billion in 2021. While Washington is calling it a big win and American businesses and farmers may be appeased by these commitments, analysts think it will be challenging for China to meet this trade goal.

Such a significant jump in its US imports will mean China reducing imports from elsewhere to balance the country’s total trade balance.

The shopping list also leaves unanswered questions: What will happen to China’s existing contracts with other countries for products like soybeans? What will happen after two years when China’s promises expire? Will the increased purchases distort the commodities markets?

Intellectual property (Chapter 1)

The 18-page-long chapter, accounting for a fifth of the full agreement, demands various commitments on the areas of trade secrets, pharmaceutical-related IP, geographical indications, trademarks, patents, e-commerce infringement, and enforcement against pirated and counterfeit goods. The theft of IP and trade secrets have been long-time concerns of American companies and was one of the main triggers for the Trump Administration’s tariff escalation. The agreement contains provisions to protect confidential information considered to be trade secrets – US companies believe this has not been sufficiently protected under Chinese law. Significant progress is also made on the protection of pharmaceutical-related IP. The agreement also calls for China to submit an “Action Plan to strengthen intellectual property protection” within 30 days of the agreement taking effect.

Technology transfer (Chapter 2)

The deal says companies should be able to operate “without any force or pressure from the other Party to transfer their technology to persons of the other Party.” Any transfer of technology or licenses between people of each country must be voluntary, according to the agreement. The two countries also agreed to a provision that would prevent either government from directing or supporting domestic companies to acquire foreign technology that could create “distortion” in sectors and industries.

Financial services (Chapter 4)

The deal includes provisions to boost Chinese market access to financial services firms. The financial services chapter sees China promising improved access to its financial services, namely, banking, insurance, asset management, and payment and fund management – addressing common complaints made by US businesses about investment barriers to China’s financial sector. Under the deal, China has agreed to move forward the deadline for removing foreign ownership caps on securities firms, which includes investment banking, underwriting, and brokerage operations, by nine months to April 1, 2020.

Currency (Chapter 5)

The deal prohibits both the US and China from manipulation of exchange rates or interest rates to devalue their respective currency. China also agreed to publicly disclose its foreign exchange reserves and quarterly imports of goods and services. Last year, the Trump Administration labeled China a currency manipulator, arguing that China was deliberately suppressing the value of its currency to give its exports a competitive advantage; this label was dropped just ahead of the signing of the phase one trade deal.

Dispute resolution (Chapter 7)

The US and China will work through their differences over how to implement the agreement through bilateral consultations, starting at the working level and then including levels with senior officials. If these negotiations fail to resolve the ongoing dispute, there will be procedures for imposing tariffs or other punitive measures.

What businesses can take away from this deal

While the deal is being touted as a win-win situation for both countries, the private sector may not yet rest easy. Businesses on both sides have had two years of instability to push them to expand their areas of operations, find new suppliers, and sell to more diverse markets, or focus on the Chinese market itself.

The phase one deal will definitely ease tensions between China and the US in the short term and might even boost American exporters in select industries. Yet, the unintended consequences of how China manages its new commitments, how other trade partners approach China going forward, and international efforts to rewrite WTO provisions on trade relationships, market competition, and state subsidies – will decide if the trade deal was worth it.

Meanwhile, much of the tariffs remain leaving less room to be upbeat for firms exposed to the trade war’s costs. Several multinational firms have already moved partial operations to third countries in ASEAN.

Chinese firms on their part, especially those in the technology sector, have suffered enough punitive consequences to trust they will have unfettered access to American markets or will be able to source from the US uninterrupted. The trade war has therefore already shaken existing global trade relationships into forging new partnerships and a renewed focus on finding alternative markets and suppliers in emerging economies.

(This article was originally published on January 17, 2020 and was last updated on March 2, 2020.)

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong.

Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com. We also maintain offices assisting foreign investors in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, United States, and Italy, in addition to our practices in India and Russia and our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative.

- Previous Article China’s Tariff Exemptions for US Imports: New Lists Announced in February

- Next Article Operating Your China Business During Contagious Disease Outbreaks – New Issue of China Briefing Magazine