An Overview of China’s VAT Reform

By Dezan Shira & Associates

Editor: Alexander Chipman Koty

Hailed as China’s most significant tax reform in over two decades, the value-added tax (VAT) was comprehensively implemented as the country’s only indirect tax in 2016, effectively replacing the business tax (BT) that previously applied to a number of industries. The reform is part of Beijing’s efforts to restructure the Chinese economy from one driven by labor-intensive manufacturing to one that is service-oriented by easing the tax burden on service industries, which have historically paid a disproportionate share.

In 2015, services made up more than half of China’s GDP for the first time, and are growing at a faster rate than any other sector of the economy. The Chinese government envisions the VAT reform to further propel growth in services and consumption as the country pivots away from the low value-added industries. The broader introduction of the VAT is also designed to encourage low-end manufacturers to upgrade their technology and capabilities, and to invest in research and development in order to move up the value chain.

China has had a VAT system in place since the country’s bold reforms and opening up to the world economy in 1979. The tax system underwent a major overhaul in 1994, as the VAT was expanded to include the sale of goods, processing, and repair services, while directing more revenue to the central government. The expansion of the VAT is expected to reduce tax payments by a total of RMB 500 billion (US$77 billion) in 2016, largely at the expense of local governments.

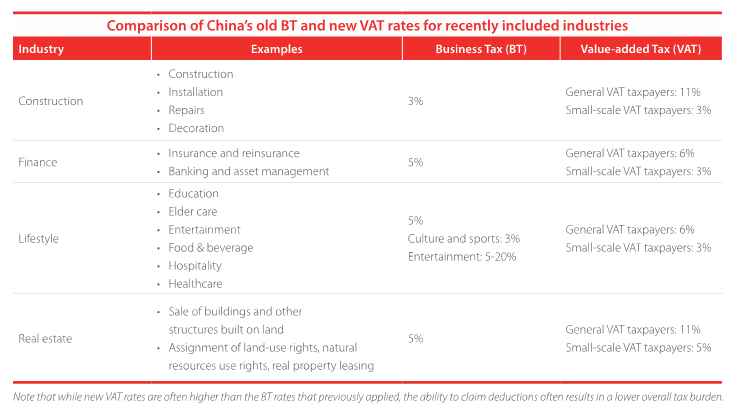

The latest phase of VAT reforms were first introduced as a pilot project in Shanghai in 2012, incorporating industries such as certain transportation and modern services, before being expanded to eight other regions in the same year and eventually being rolled out nationwide on August 1, 2013. By the end of 2015, modern services, postal services, telecommunication services, and transportation services were all fully included under the VAT regime nationwide. The Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation jointly issued Caishui [2016] No. 36 (Circular 36) on March 23, 2016, which announced that the major industries still paying BT would be transitioned to the VAT regime. Effective as of May 1, 2016, the construction, finance, lifestyle, and real estate sectors were introduced to the VAT, essentially eliminating BT from China’s tax system.

![]() RELATED: Tax and Compliance Services from Dezan Shira & Associates

RELATED: Tax and Compliance Services from Dezan Shira & Associates

Key features of the VAT reform

The VAT more closely aligns China’s tax system with international standards, though it still contains its own unique characteristics and complexities. Previously, VAT existed alongside BT, according to the relevant industry. VAT allows businesses to offset VAT incurred on relevant purchases from their own VAT liability, while BT applied to gross turnover, with no deductions for purchases of relevant goods and services.

Historically, manufacturing and other industrial firms operated under the VAT system, while most services fell under the BT. This meant that service industries faced higher taxes, as they encountered revenue-based taxes accumulated across their supply chains, while not benefiting from the deductions allowed by VAT. With this latest reform, service industries also enjoy generally reduced tax rates, as they are only taxed on the value added at each transaction, such as the difference between the wholesale and retail price of a given product. In such instances, the input VAT (e.g. on the wholesale good) can be deducted from the output VAT (e.g. on the retail good).

Taxable activities are separated into three main categories for VAT calculation purposes, namely the supply of services, the supply of intangible assets, and the supply of real estate. Supply of any service under these three main categories falls under the jurisdiction of VAT, unless specifically excluded. According to Circular 36, items outside the scope of VAT include insurance compensation obtained by the insurant and interest accumulated on deposits, among others.

While most services are part of the general category “supply of services”, the “supply of intangible assets” has a far broader definition in Circular 36 than under the old BT regime. Franchise rights, memberships, and virtual products like internet games and domain names are now explicitly considered intangible assets, which was unclear under BT. As such, it is recommended that businesses review whether VAT now applies to certain assets that were exempt from BT.

Under VAT, businesses are considered either general taxpayers or small-scale taxpayers based on their annual sales. Small-scale taxpayers – those collecting less than RMB 500,000 in revenue – benefit from a lower VAT rate of three percent, compared to the six to 17 percent levied on general taxpayers, depending on their industry.

While small-scale taxpayers enjoy lower tax rates, they may struggle to compete with larger companies in the long term. Although assessed at a higher uniform tax rate, only general taxpayers are entitled to credit input VAT from output VAT and VAT export exemptions and refunds. As such, the reform rewards large businesses that have complex supply chains and numerous transactions, while also giving them a competitive edge by reserving them the ability to issue special VAT invoices (fapiao). Special VAT invoices are needed to deduct input VAT, meaning that buyers will generally prefer to purchase from entities able to issue such invoices to offset their own taxes.

Newly covered industries

The last round of BT to VAT reforms brought several industries instrumental to the Chinese economy under the jurisdiction of the VAT. The real estate, construction, finance, and lifestyle services sectors made up 80 percent of total BT revenue before the tax was scrapped. Although the reform broadly aims to reduce corporate tax burdens, in the case of such a sweeping change, there are inevitably winners and losers.

For example, the real estate and construction industries are closely intertwined, though the former benefits from the VAT reform more than the latter. Developers can get a VAT input credit for land use rights purchases, and therefore only need to pay taxes on the value they add to the property. However, those in the construction industry have fewer opportunities to claim VAT credit, since labor costs are not deductible and several raw materials, such as sand and gravel, are not considered to involve any value added.

As such, when analyzing the impact of VAT on business operations in China, it is essential to take an integrated approach that includes the implications not only to one’s direct business scope, but also the impacts on suppliers and customers. The specificities of VAT levies often differ based on types of transactions within a given industry, and in certain cases, further clarification from the government is still needed. Although VAT is now universal as an indirect tax in China, the system remains complex. Careful consideration of its impacts on tax optimization and compliance is vital to healthy business operations in the Middle Kingdom.

This article is an excerpt from the November issue of China Briefing Magazine, titled “Evaluating China’s VAT Reform.” In this issue of China Briefing, we walk readers through some of the most salient aspects of the VAT reform affecting foreign businesses in China. This article is an excerpt from the November issue of China Briefing Magazine, titled “Evaluating China’s VAT Reform.” In this issue of China Briefing, we walk readers through some of the most salient aspects of the VAT reform affecting foreign businesses in China. |

Establishing & Operating a Business in China 2016

Establishing & Operating a Business in China 2016

Establishing & Operating a Business in China 2016, produced in collaboration with the experts at Dezan Shira & Associates, explores the establishment procedures and related considerations of the Representative Office (RO), and two types of Limited Liability Companies: the Wholly Foreign-owned Enterprise (WFOE) and the Sino-foreign Joint Venture (JV). The guide also includes issues specific to Hong Kong and Singapore holding companies, and details how foreign investors can close a foreign-invested enterprise smoothly in China.

China Investment Roadmap: the Education Sector

China Investment Roadmap: the Education Sector

In this issue of China Briefing, we navigate through China’s regulatory framework for investment into education, presenting a roadmap for best practices in the industry. We examine the key market information that has driven the industry’s growth, analyze the different investment models that are available for foreign companies, and finally discuss the effect that China’s recently released NGO law will have on foreign investment into education.

Understanding Mergers & Acquisitions in China

Understanding Mergers & Acquisitions in China

In this issue of China Briefing magazine, we set out to guide foreign investors through the mergers and acquisitions process, from initial market research, to set-up procedures and regulatory hurdles, and finally through important due diligence considerations. With experience in China’s M&A market since 1992, Dezan Shira & Associates is perfectly positioned to ensure that the M&A is the right investment vehicle for your company’s venture into China.

- Previous Article Mapping the Rise of China’s Commercial Drone Industry

- Next Article Vue d’Ensemble des Prix de Transfert en Chine