Internal Control and Fraud Prevention in China

Jul. 25 – In light of the ongoing GSK investigation and pharmaceutical industry issues concerning bribery and corruption in China within the sales force, this article looks at the aspects of fraud in the Chinese workforce. Although this scandal comes as no surprise for many familiar with the market (China’s own distribution apparatus is highly corrupt), the spotlight is increasingly turning onto foreign investors in times of increased economic uncertainty and domestic political pressures. This means that the awareness of fraud has increased, along with the value placed on internal control in preventing fraud.

Jul. 25 – In light of the ongoing GSK investigation and pharmaceutical industry issues concerning bribery and corruption in China within the sales force, this article looks at the aspects of fraud in the Chinese workforce. Although this scandal comes as no surprise for many familiar with the market (China’s own distribution apparatus is highly corrupt), the spotlight is increasingly turning onto foreign investors in times of increased economic uncertainty and domestic political pressures. This means that the awareness of fraud has increased, along with the value placed on internal control in preventing fraud.

The tenets of internal control do not vary with geography; effective internal control systems in China are quite similar to those for companies in New York and Milan. However, when operations – shielded by a language barrier and less than transparent business environment – take place on the opposite side of the globe from senior management, internal control systems graduate from a contributor to business effectiveness to a necessity for business survival.

The Chinese business context holds increased risks for violation of certain aspects of internal control and a different understanding of implementation of internal control systems and internal audits. These are particular challenges for companies subject to compliance with a parent company’s code of conduct and/or regulations from other countries, such as the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

Defining Internal Control and Audit

Internal control and audit are a pair – the former a process and the latter a check of the quality of the process.

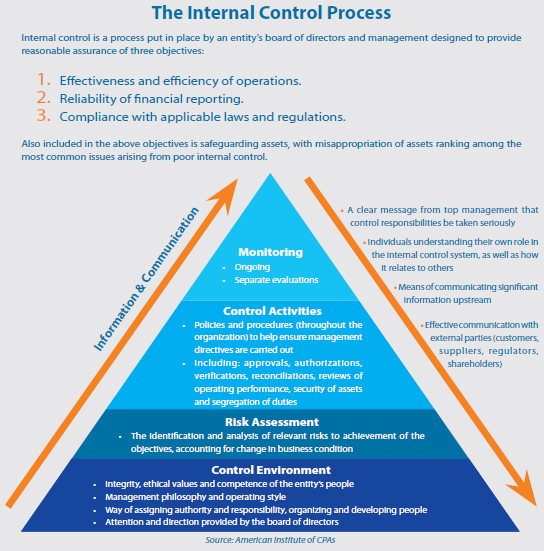

The internal control process is designed to provide reasonable assurance of three objectives:

- Effectiveness and efficiency of operations

- Reliability of financial reporting

- Compliance with applicable laws and regulations

Also included in the above objectives is safeguarding assets, with misappropriation of assets ranking among the most common issues arising from poor internal control.

An effective internal control system is monitored both continuously and with separate evaluations, while conducting due diligence prior to acquiring a company or hiring senior personnel is just a one-time, preventative check.

An internal audit evaluates the effectiveness of risk management, control, and governance processes from a systematic and disciplined standpoint. And an internal audit ordered directly by a company’s headquarters is the best way to uncover and prevent fraud in a China-based entity for several reasons.

First and foremost, an internal audit engaged by the China-based entity itself reports only to that entity. If fraud is discovered at a local level, it may not be reported directly to company headquarters.

In one recent case, explains Dezan Shira & Associates Audit Manager Ronin Lin, significant sales department fraud (including submitting fake invoices) was being willingly overlooked at the local level, as the department was doing well. Because the local entity engaged the internal audit, the audit team did not report the situation to the headquarters abroad.

An internal audit of a China-based entity ordered by headquarters holds an additional benefit – maintaining trust and confidence between China-based management and staff. As the local management did not order the audit, there is no suggestion of faltering trust or loss of confidence.

While it is management’s responsibility to establish and maintain an entity’s internal controls, hiring a professional service firm to conduct an internal audit or other type of assurance service (customizable to the specific information needs of decision makers) can uncover systemic weaknesses. Internal audit professionals that have a macroview of a company can play a significant role in strengthening your internal control system over time.

“In addition to what’s required by law, audit comes in many forms,” explains Lin. “We typically recommend one of two types of assurance to our clients: a ‘house check’ or a ‘full scope.’ In a ‘house check,’ we run through a general internal control checklist and try to gauge whether an organization is under control risk. This basically means that there is a predefined internal control protocol in place, and that an organization’s reports reflect reality. This type of assurance, which requires significantly less money and energy than a ‘full scope’ assurance, can determine whether the latter is necessary.”

Fraud Risk in China

With multiple instances of very large-scale fraud from hitting the news recently, more than a few people have paused to consider how fraud risk in China may be different from that in other geographic locations. The most widely accepted answer seems to be: “It’s not. But…”

But the opportunities for fraud in China are simply greater than in many other locations – business transactions are less transparent and the language barrier a thick shield. While anyone who suggests that Chinese culture has an influence on the prevalence of fraud will immediately be shot down – fraud is a product of humans acting in self interest and nothing else – certain characteristics of Chinese business culture can have a huge impact on fraud prevention.

It is widely acknowledged, for example, that contracts are seen as substantially less important in China than elsewhere, leaving greater room for fraud. In addition, the approach that companies in China take to dealing with fraud may differ from that in other countries. Punitive action after fraud is discovered is often not as severe, which encourages fraud in the first place.

Fraud in China varies significantly, from petty cash fraud to very sophisticated fraud, deeply entrenched in an organization’s operations. Internal control to protect intellectual property (IP) is also a point of increasing concern, as a lot of companies in China have graduated from a manufacturing focus to a model where their real business value is in their intellectual property.

“Fraud risk can also vary significantly with the complexity of an organization’s structure,” according to Lin. “While a trading company (foreign-invested commercial enterprise, or FICE) requires one of the most straight-forward internal control systems, organizations with a lot of marketing and those that deal with many vendors and a complex supply chain have a high risk of fraud.”

In fact, even with the most simplistic business model, inappropriate behavior uncovered by internal audits can be quite deep in a company. Lin details another recent internal audit which uncovered contracts showing that a general manager was renting his own houses to the joint venture company (without the slightest rationalization for how this was related to business operations). The twist to the situation was that the GM was one of the majority shareholders of the joint venture (but, needless to say, the only one aware of the rental contracts).

Operations with elevated fraud risks within China-based enterprises include supply chain management, payroll management, and sales.

Supply chain

- Purchasing of overpriced raw materials (due to relationship/inappropriate agreement between staff and supplier)

- Improper disposal of scrap

- Fake VAT invoices

- Poor inventory control

Payroll

- Discrepancy between contract salary and payroll payments

- Deliberate over-accrual/unauthorized use of welfare benefits

- Ghost employees

- Unauthorized/improper reimbursements

- Non-payment of taxes and social security

Sales

- Sales of goods at/below cost (due to relationship/inappropriate agreement between sales staff and purchaser)

- Payment of unauthorized sales commissions to employees or friends

- Lack of competitive bidding process

Preventing Fraud in China

For foreign-invested enterprises in China, preventing fraud means increasing vigilance in strengthening internal control systems. Fraud prevention should be based on the “fraud triangle” –

- Motivation;

- Rationalization; and

- Opportunity.

Internal control is focused on limiting the opportunity corner of the fraud triangle. A key example is strengthening the physical security of inventory – not what’s on the books, but the systems in place to carefully monitor what enters and leaves a facility.

For example, a China-based clothing manufacturer ordering huge quantities of fabric had an employee who was purposely mislabeling good material as scrap and selling it at a low price to a separate company (in which they had a business interest) to produce counterfeits.

Recruitment is one of those areas that allows you to expand into the motivation corner of the fraud prevention triangle. Pre-employment screening should be done for all sensitive posts, i.e. those in the “fraud potential zone.” The “fraud potential zone” includes senior positions in the finance and procurement departments, as well as sales, supply, marketing warehousing and distribution.

Pre-employment screening is a bit challenging in China because labor law favors the employee, and if a company discovers fraudulent behavior, it may choose to protect itself from any potential litigation and sign a mutual-termination agreement with the employee. If a new prospective employer asks the employee why they left the post, he or she will probably vaguely cite mutual termination. As such, a discreet investigation can figure out if unethical behavior was in fact the cause for termination.

The rationalization corner of the fraud prevention triangle is hardest to deal with in internal control. One place to consider it, however, is with procurement staff and suppliers, who are often dealing with thin profit margins. As these are already in the “fraud potential zone,” a closer look can clarify whether procurement staffers are acting in the best interests of the company and suppliers following their original contract obligations.

Below, we provide an internal control checklist to help foreign enterprises in China limit their risk of fraud while operating in the country.

Dezan Shira & Associates is a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email china@dezshira.com, visit www.dezshira.com, or download the company brochure.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across China by subscribing to Asia Briefing’s complimentary update service featuring news, commentary, guides, and multimedia resources.

Related Reading

Internal Control and Audit

Internal Control and Audit

This issue of China Briefing Magazine is devoted to understanding effective internal control systems in the Chinese context and the role of audits in detecting and preventing fraud.

The China Tax Guide: Tax, Accounting and Audit (Sixth Edition)

The China Tax Guide: Tax, Accounting and Audit (Sixth Edition)

This edition of the China Tax Guide, updated for 2013, offers a comprehensive overview of the major taxes foreign investors are likely to encounter when establishing or operating a business in China, as well as other tax-relevant obligations. This concise, detailed, yet pragmatic guide is ideal for CFOs, compliance officers and heads of accounting who need to be able to navigate the complex tax and accounting landscape in China in order to effectively manage and strategically plan their China operations.

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and its Impact on China Subsidiaries

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and its Impact on China Subsidiaries

This issue of China Briefing Magazine is dedicated to helping companies understand the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and establish controls to prevent (and, if necessary) resolve FCPA noncompliance.

Financial Management

Financial Management

This issue of China Briefing details FCPA regulations, fraudulent accounting practices within Chinese companies and due diligence issues for IPO listings. It also covers PRC GAAP regulations, compliance with them and the differences between EU and U.S. standards.

The China Manager’s Handbook

The China Manager’s Handbook

Stories of expats having their name added to the Administration of Industry and Commerce “blacklist,” or being “trapped in China” for company legal proceedings, encourage a careful consideration of key positions in an FIE. This issue of China Briefing Magazine aims to shed a little light on this topic.

Internal Control and Anti-Corruption Regulations in China

The Duties and Liabilities of Key Personnel in a Foreign Company in China

- Previous Article Why Corruption is Inevitable in China’s Pharmaceutical Industry

- Next Article China Releases Final Draft of New Visa and Residence Permit Regulations for Foreigners