Mitigating Against China’s Power Shortages

Short-term problems will be managed with solutions both available and in sight.

By Chris Devonshire-Ellis

China has been experiencing what many analysts have been suggesting are ‘power shortages’ with these occurring in the North-East part of the country and Guangdong. Reports in the media concern factory closures shutting down production in both upstream and downstream industries on an increasing scale and beginning to affect the economic powerhouses of Jiangsu and Guangdong, with consumer manufacturing companies being forced to close.

The concern is that this will exacerbate global shortages in supply chains. Although many BRI economies, as resource producers, are evidencing booming conditions for their exports to China (and elsewhere), energy prices are soaring, from oil to gas to coal, particularly as demand for power in China surges. The same is true for agriculture products like grains, as feed for China’s pigs and cattle stocks, where prices are also beginning to surge.

Why is this happening?

China’s power crunch has been caused by tight coal supplies and toughening emissions standards.

Experts point out that thermal power still accounts for more than half of China’s electricity supply. Under the background of rising coal prices in the upstream and limited room for increasing power supply prices in the downstream, thermal power enterprises are reluctant to generate electricity, which directly leads to power shortage. This is the main reason for the power shortage in many places, especially in the north.

Besides, influenced by the “reverse investigation for 20 years” of the Inner Mongolia’s coal corruption, the safety supervision, and the environmental protection efforts, the coal production capacity has been reduced to a large extent and caused the coal shortage.

In addition, due to economic recovery, the power demand increases a lot due to the surge of orders. From January to August, China’s electricity consumption increased by 13.8 percent, mainly due to strong demand in the secondary industry. Power consumption in Guangdong, the Yangtze River Delta and other regions grew faster than the national average.

Factories are being idled to avoid exceeding limits on energy use imposed by Beijing to promote efficiency. Economists suggest that manufacturers have used up this year’s quota faster than planned as export demand rebounded from the coronavirus pandemic.

Impact

The suspension of production at some factories has prompted concerns over the possible shortage of goods ahead of Christmas, including smartphones and devices.

What will China do?

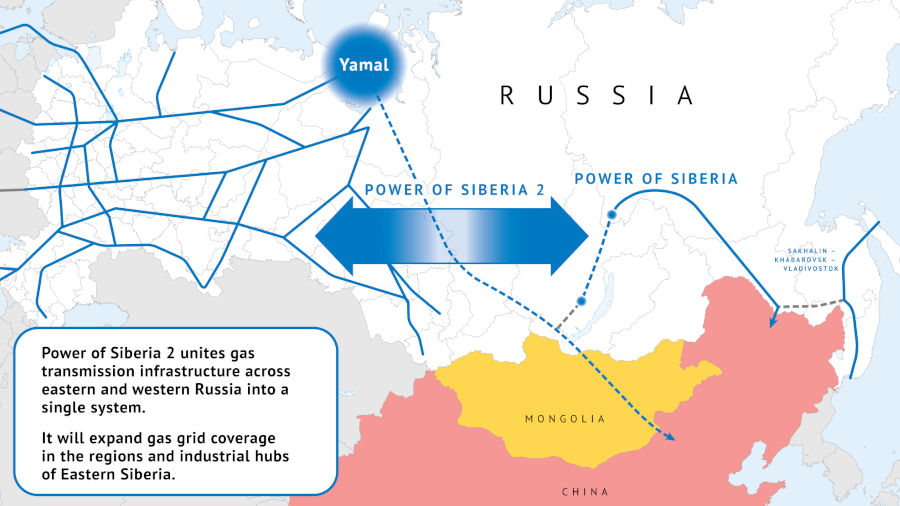

The issue is not so much a lack of energy supplies, but a lack of the right type of energy supplies. Beijing has committed to reducing coal burning output from its power stations and has based much of the replacement energy on gas supplies from Russia, and especially the ‘Power of Siberia’ pipelines. However, the second gas pipeline is not due to come in play till 2022, meaning an under-appreciation of usage after COVID has caught Chinese energy analysts a few months short. This has occurred just as winter approaches and domestic consumer demand, especially in China’s north, increases.

Beijing will be reluctant to relax environmental standards just as it stated its intent to be globally responsible and with the climate change COP26 meeting in November: China wants to be seen to be taking the lead here. On the other hand, there are additional circumstances that create pressure on the CPC. Shijiazhuang and Heilongjiang Province, both in North China, are due to host the Winter Olympics from early February, for which blue skies will be required in front of a global TV audience.

China hosted the Summer Olympics in 2008 and to ensure blue skies then, shut down polluting factories within a 250km radius of the city four months beforehand. There is precedence – albeit that winter in North China can get very chilly.

The US also has a role to play – the federal government is largely responsible for producer prices and the cost of energy. If it wishes to squeeze China, it can, although Russia may wish to break away from its globally imposed high energy prices to China to support Beijing. Russia can afford it, and such a move may give Moscow some leverage over Beijing in other areas. The US must also be careful in not leaving it too late in acting on energy prices as the later it does so, the greater the stresses on an already indebted global economy.

In the past, China has dealt with energy shortages on a rota system. Twenty years ago, the country experienced brown-outs as manufacturing boomed at a time when the national energy grid wasn’t sufficiently developed to cope. Essential services were maintained, then a system of communal sharing introduced. Factories were zoned into physical locations and told in advance – a crucial issue when planning manufacturing – when power would be diminished. Some industries reliant on constant energy supplies did experience some problems, however, such as glass making kilns where furnace temperatures need to be maintained or they are badly damaged. That led to a re-classification of business types in China. Certain industries were encouraged to invest in pertinent back-up generators, which maybe an option today for some foreign investors. In any event, the brown-outs, which began somewhat chaotically, were managed for a period for about nine months before normal service was resumed after the national grid caught up with demand. The same will happen on this occasion.

Concerning Christmas, and toy supplies, things have changed since the early 2000’s when Guangdong manufactured 95 percent of the global demand for Christmas Trees and their decorations. China has moved up the production value chain the past two decades: none of the world’s largest toy manufacturers are Chinese, although sub-contracting manufacturing to China does of course happen. However, even that has been reduced in recent years and especially to the US market as Donald Trump’s tariff wars a few years back encouraged products to be manufactured elsewhere, such as Vietnam.

This became an effective extension of the ‘China Plus One’ business model, which saw foreign investors split their China manufacturing into two components – one based in China to service the China domestic market (which doesn’t celebrate Christmas) and another, based elsewhere in locations, such as Vietnam, India, Thailand, Philippines, or Bangladesh to service the export market. This remains a sound strategy.

So how will things pan out?

* The Fed will have to relax on the production costs and arrange with OPEC and other global bodies to reduce oil and gas prices.

* China will manage its own shortages and while these may be inconvenient, they will be shared. Power of Siberia will provide a solution from 2022.

* The circumstances provide another lesson for reconsidering a China Plus One approach if this has not already become part of your production strategy.

In short – Don’t Panic!

Related Reading

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article The Supreme Court’s Decision Against 996: Looking from Inside

- Next Article EU’s New Strategy on China: Implications for Businesses