The UK Needs a Reset with China. This is What it Can Do.

- London appears fixated on pre-1997 Hong Kong

- The UK’s sole bilateral investment treaty dates to 1986

- Beijing reset trade ties with Brussels and the EU in January

- The UK remains out of the loop from a China consumer market set to double in a decade

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Last week, the British Government released its new Foreign Policy, that in part aims to deal with the aftermath of Brexit and focus attention on a growing China. Most of the China text was based on plans to be announced shortly, which include investing in “China-facing capabilities” and to “better understand and respond to the systemic challenge that China poses.” Trade was left on the backburner and has instead been replaced with an attitude that views China as a quasi-threat.

A post-Brexit UK has been left somewhat behind in dealings with China. During the heady days when then Prime Minister David Cameron shared a pint of beer with Chinese leader Xi Jinping in 2015, UK exports to China were worth £18.9 billion; this grew to £30.7 billion by 2020 at an annual growth rate of about 12 percent.

One would have thought that would be encouraged – yet the opposite has happened. The UK Government did not act honorably over Chinese investments in nuclear power or 5G, where deals were in place, and the Chinese quite capable and competitive. US pressure however led to these being nixed. Today, we have a somewhat idiotic diplomatic stand-off with Beijing concerning Hong Kong, with the UK Government signing off on a G7 critique of China’s attitude towards democracy in the territory. However, London did not permit democracy in Hong Kong since the UK first took it as a possession – by force – in 1839 until it was handed back in 1997. Instead, a succession of Governors were appointed, from London, to administer the territory. It is a hypocritical position, and Beijing knows this.

There are certain political noises being made that are not in Beijing’s favor but who claim to be representing British business interests. These include the influence of Jardine Matheson, whose businesses have been entwined with China since 1842. The company has always been based in Hong Kong, yet at the time of the 1997 handover to China relocated its domicile to Bermuda and subsequently listed its operations in London and Singapore instead of its more natural home. That was partially in fear of Chinese retribution to Jardines involvement in the sleaze of the Opium Wars.

However, some 58 percent of Jardine’s profits were realized from China trade in 2019, while two Jardines businesses are among the top 200 most traded shares globally. Jardine Matheson has a market capitalization of US$48.78 billion and Jardine Strategic of US$33.08 billion. Such figures matter in London, which is understandable. However, whether it remains the wisest approach to follow political advice from a company that has effectively shunned contemporary Hong Kong and has no public listed experience in China either is a moot point. Jardines fundamental flaw is that they are unable to participate in raising capital from mainland China, or able to benefit from Hong Kong’s increasing role as a financial services center as part of the Greater Bay Area. Instead, they are stuck in a pre-1997 mentality as concerns dealing with Beijing and are unable to look ahead towards the coming potential and possibilities.

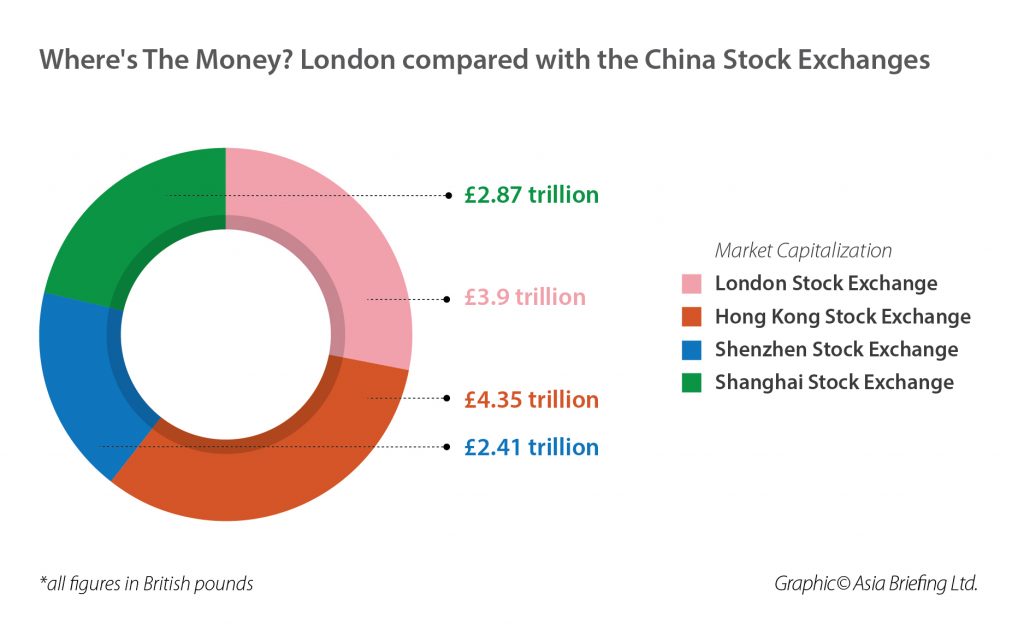

That is a problem when Jardines remain influential in UK-China political assessments. It is an outdated mentality, based on the days when the London Stock Exchange was Asian influential, and Bermuda considered a better home than Hong Kong for a China business, an issue which appears anachronistic today. Let us look at the market capitalization of the London and the China exchanges as they are now, 24 years after the handover to Hong Kong:

What should be happening is UK financial services firms should be looking to Hong Kong to access the estimated US$3 trillion of private wealth locked up in China. Instead, the UK is getting involved in political arguments with Beijing that are dubious at best and that can never be won. The much-vaunted London-Shanghai Stock Connect has been suspended since January 2020 because of the diplomatic spats – costing the city of London billions in fees and lost, wasted relationships.

Additionally, in time, the Shenzhen and Shanghai stock exchanges will be open to foreign listings. Some concessions and experiments have already been taking place to do just that. But the attitude of companies, such as Jardines, has been to avoid that experience or attempt to gain that expertise. It is creating a future knowledge gap that dissuades UK plc from engaging with one of the world’s largest and fastest growing consumer markets.

The UK has also been tardy when it comes to trade promotion. A multi-faceted approach combining private trade membership entities, such as the 48 Group, the China-Britain-Business Council, five geographic Chambers of Commerce in China, countless examples of the same back in the UK, coupled with diplomatic staff in six diplomatic missions in China as ‘commercial consuls’ and hundreds of trade missions over the years have failed to provide any tangible trade agreements. They have effectively divided and failed to conquer any trade concessions for the past thirty-five years. That multi-tiered approach has been confusing and divisive, failing thus to work out a concrete, all-encompassing China strategy.

As a result, the last UK-China trade deal was in 1986, in the UK-China bilateral investment treaty, an arrangement that primarily deals with services and protection of each nation’s investment, but is pre-internet and has no specific provisions, for example, for the UK’s IT industry. Yet, in 2019, the UK IT sector’s technical consumer goods industry generated revenues totaling £12.72 billion. None of that is specifically protected or encouraged under the current terms with China – and that is just one sectoral example.

In contrast, one of the first acts of trade that the EU accomplished after Brexit was done, was the signing of the Comprehensive Investment Agreement (CAI), which is a similar type of document to the UK-China bilateral investment treaty but far more comprehensive. The CAI’s main objectives are an enhanced protection of EU investments in China and vice versa, improved legal certainty regarding the treatment of EU investors in China, the reduction of barriers to investing in China, and as a result, increasing bilateral investment flows and improved access to the Chinese market. It remains unclear where any UK initiative in upgrading, modifying, and expanding the UK-China bilateral investment treaty stands; however, given the current toxic nature of UK-China relations, it is safe to say there’s little, if any progress.

London needs to have a rethink and to spread its circle of influencers when it comes to China. Politicians such as Chris Patten (Governor of Hong Kong a quarter of a century ago) and the likes of Jardine Matheson have failed to keep up to date with Beijing, the progress it has made, and the reality of a changing Hong Kong and developing China. The current situation has become stuck in a rut; negativity and mistrust have taken the place of open engagement. More contemporary voices and thinking need to be given a platform. A better channeled and diplomatic effort should be put in place of the current archaic and scattergun approach.

At the same time, thought needs to be put into revamping the investment treaty. London’s approach to developing Asia trade, and discussing relations with ASEAN, engaging with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) are admirable and worthwhile, if a little sluggish in development. However, if the UK does not engage properly with China, then the EU will, and has done despite having its own political differences with Beijing. Brussels has achieved a pragmatic balance, whereas London has not, and is stuck in a type of self-created no-man’s land.

Morgan Stanley predicted in January that Chinese private consumption will likely grow by about 7.9 percent a year in the next decade, one of the highest levels in the world. British exporters and service providers need a China reset from London to take advantage – or they will lose out.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article Norway and China Strive to Complete Free Trade Agreement Negotiations

- Next Article Belt and Road Weekly Investor Intelligence, #20