China’s 2022 Economic Outlook Based on GDP and Economic Indicators from 2021

China’s economic outlook for 2022 will depend on exports performance, pace of recovery of the property industry, and whether domestic consumption can rebound. China’s economy is mainly driven by exports and industrial production and its services sector, domestic consumption, and investment have not yet fully recovered. Latest economic data from 2021 show that the country is facing mounting downward pressures, mainly due to a property downturn, shrinking demand, and diminished support from exports. The Chinese real estate sector continues to struggle under the government’s deleveraging efforts. COVID-19 and sluggish household income growth are weighing on consumption. Exports performed strong in 2021 but started to show signs of a slowdown in Q4.

China’s economy expanded 8.1 percent in 2021, matching market expectations. The full-year GDP came in at RMB 114.4 trillion (US$17.7 trillion), with an increase of about RMB 13 trillion (US$3 trillion) compared to 2020.

As the world’s second-largest economy, China is expected to account for more than 18 percent of the global economy and contribute more than 25 percent of global economic growth in 2021, according to the country’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

The GDP growth rate easily topped Beijing’s target of “above six percent”, thanks to a sustained export boom and a low comparison base – in virus-ravaged 2020, the economy grew merely 2.2 percent.

Slipping economic growth momentum

In the last quarter, China’s GDP grew four percent from a year earlier, down from the 4.9 percent growth in Q3, the 7.9 percent in Q2, and the 18.3 percent in Q1. Despite the slowdown, the Q4 GDP year-on-year growth exceeded economists’ forecasts of 3.6 to 3.7 percent, and on a quarterly basis, it grew a moderate 1.6 percent.

The lower GDP growth in Q4 was a result of a combination of factors – a less favorable comparison base, a property downturn under the government’s continued deleveraging efforts, virus disruptions, weak domestic spending, and diminished support from exports.

Looking ahead, economic growth in 2022 faces various headwinds. Ning Jizhe, head of the NBS, warned China is now facing “triple pressures from shrinking demand, supply shocks, and weakening expectations”. Compounding the problem is a worsening demographic picture – in 2020, the birth rate in China fell to its lowest point in more than four decades, at a faster-than-expected pace.

Economists predict that Beijing will roll out monetary easing and fiscal support policies this year, to counter a loss of economic momentum.

A closer look at China’s 2021 macroeconomic figures

Economic data show that China’s economy is mainly driven by strong industrial output and exports. In 2021, the two-year average growth of industrial output exceeded the pre-COVID-19 level in 2019 and the year-on-year growth rate of exports in dollar terms hit the highest level since 2011. However, the two-year average growth of services, consumption, and investment all failed to return back to the pre-pandemic trajectory, which dragged down the wider economic performance.

Here are some recent macroeconomic highlights from China:

- GDP growth slowed to four percent in Q4 but still grew by 8.1 percent for the full year.

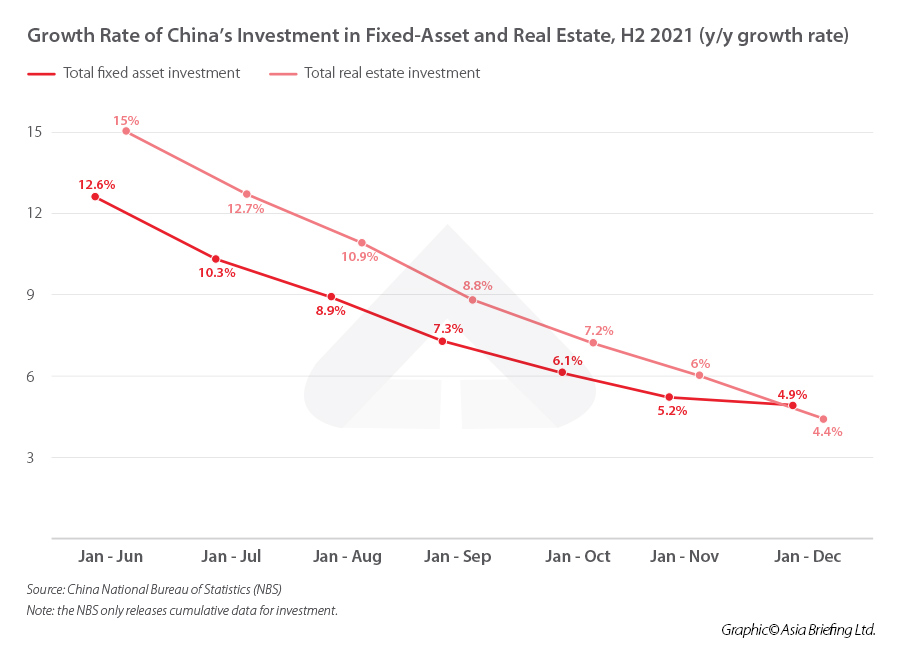

- Total fixed asset investment went up by 4.9 percent in Q4, down from 7.3 percent in the first three quarters.

- Total real estate investment increased by 4.4 percent in Q4, down sharply from 8.8 percent in the first three quarters.

- Growth of industrial added values rose by 9.6 percent in Q4, down from 11.8 percent in the first three quarters.

- Total retail sales of consumer goods went up by 12.5 percent in Q4, down from 16.4 percent in the first three quarters.

- Imports and exports increased by 21.4 percent to reach RMB 39.1 trillion (US$ trillion) in Q4, slower than 22.7 percent in the first three quarters.

- PMI stood at 50.3 percent in December, 0.2 percentage points up from that in November.

On the demand side, investment made a surprisingly negative contribution to GDP growth in Q4 at -11.6 percent. This is mainly because the government’s deleveraging efforts led to a sharp drop in real estate investment, which further impacted secondary sector output growth.

While investment in manufacturing continues to recover, among which investment in high-tech manufacturing increased 22.2 percent for 2021, it has been insufficient to recoup the overall loss.

China’s net exports contributed a much-needed 26.4 percent in Q4, indicating that a sustained export boom has prevented a worse economic slowdown by the end of 2021. However, exports growth showed signs of slowing in the last quarter as developed countries withdrew stimulus packages, leading to a pullback in external demand.

Real estate and infrastructure investment remained subdued, while manufacturing investment was relatively strong

China’s fixed-asset investments – including investment in infrastructure, machinery and equipment, and real estate development – grew 4.9 percent for the whole of 2021, down from a 5.2 percent expansion for the first 11 months.

Of it, investment in real estate saw a sharp drop, as the government restricted developer financing and home purchases in an effort to curb property speculation and credit expansion. In the second half of 2021, the cumulative year-on-year growth of real estate investment dropped from 15 percent to 4.4 percent.

Although debt restrictions eased in Q4, year-on-year growth of real estate investment further slowed to 4.4 percent in the January-December period from a six percent increase for the first 11 months.

Infrastructure investment grew at a snail’s pace last year, which rose a slight 0.4 percent for the full year, down from a 0.5 percent growth pace in the first 11 months. Land sales slump and tightened regulation of local government hidden debt have constrained investment in infrastructure.

Manufacturing investment continued to pick up. Investment in manufacturing grew by 13.5 percent in 2021 from a year ago, with investment in special purpose machinery rising the most, up 24.3 percent year-on-year.

Imports and exports are strong, but show signs of slowing

China enjoyed a strong trade performance in 2021. Remarkably, its trade surplus hit a record high at US$676 billion, up 26 percent from the previous year.

Imports and exports totaled US$6.05 trillion, with a year-on-year increase of 30 percent, of which:

- Exports reached US$3.36 trillion, up 29.9 percent year-on-year; and

- Imports reached US$2.69 trillion, up 30.1 percent year-on-year.

Total trade achieved double-digit gains in every single month of 2021.

As a result, China’s share of the global export market continues climbing. This figure jumped to 14.7 percent in 2020 and 14.9 percent in the first three quarters of 2021 – from 13.1 percent before the pandemic.

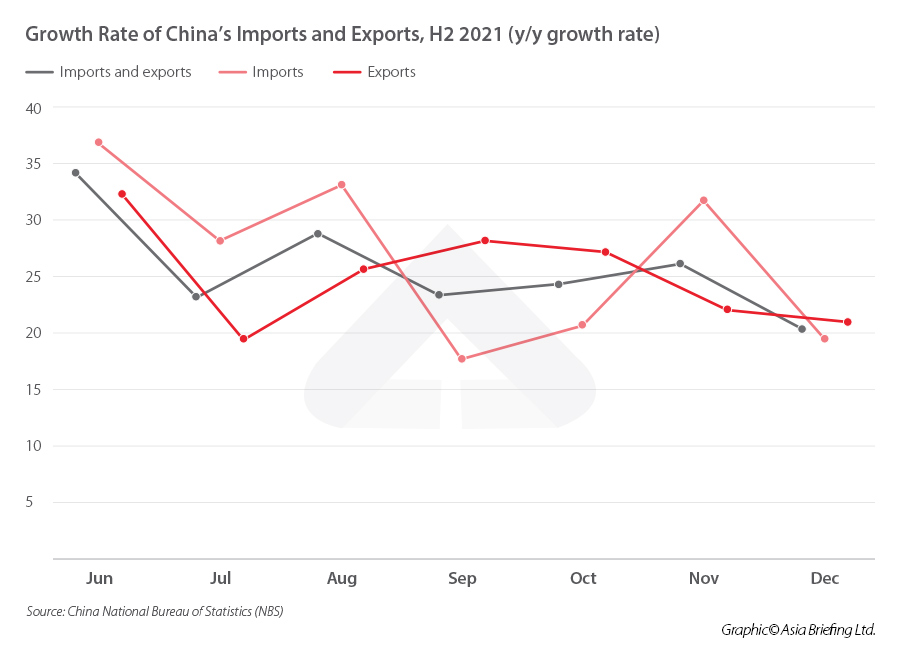

|

Year-on-Year Growth Rate of China’s Imports and Exports, H1 2021 |

|||||||

| Jun | July | August | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Imports and exports | 34.2% | 23.1% | 28.8% | 23.3% | 24.3% | 26.1% | 20.3% |

| Exports | 32.2% | 19.3% | 25.6% | 28.1% | 27.1% | 22.0% | 20.9% |

| Imports | 36.7% | 28.1% | 33.1% | 17.6% | 20.6% | 31.7% | 19.5% |

While goods are still being shipped abroad at an impressive pace, China’s export growth slowed for the third month in a row in December as exports rose by only 20.9 percent year-on-year, down 22 percent from November.

With the rest of the world shifting towards a “living with COVID” strategy in 2022 and countries scaling back on government stimulus spending, a decline in overseas demand for Chinese products is projected to lead exports to fall, in turn adding pressure on Chinese officials to consider more local stimulus to boost domestic demand.

Imports, on the other side, increased 19.5 percent year-on-year in December, down from 31.7 percent growth in November, which missed expectations that they would increase around 28 percent in December. This also partly reflects the shrinking domestic demand.

China’s trade with the US and Australia surges

Notably, the US remained China’s largest trading partner on a single-country basis at a time when the US-China phase one trade deal expired at the end of 2021.

China’s exports to the US rose 27.5 percent for 2021 to US$576.11 billion and imports grew 32.7 percent to US$179.53 billion. China’s trade surplus with the US reached US$396.58 billion, marking the second straight year the surplus has risen since a drop between 2018 and 2019.

In addition, China’s trade with Australian also grew last year despite bilateral tensions. The exports to Australia grew 24.2 percent, while imports climbed by 40 percent.

Industrial output accelerates

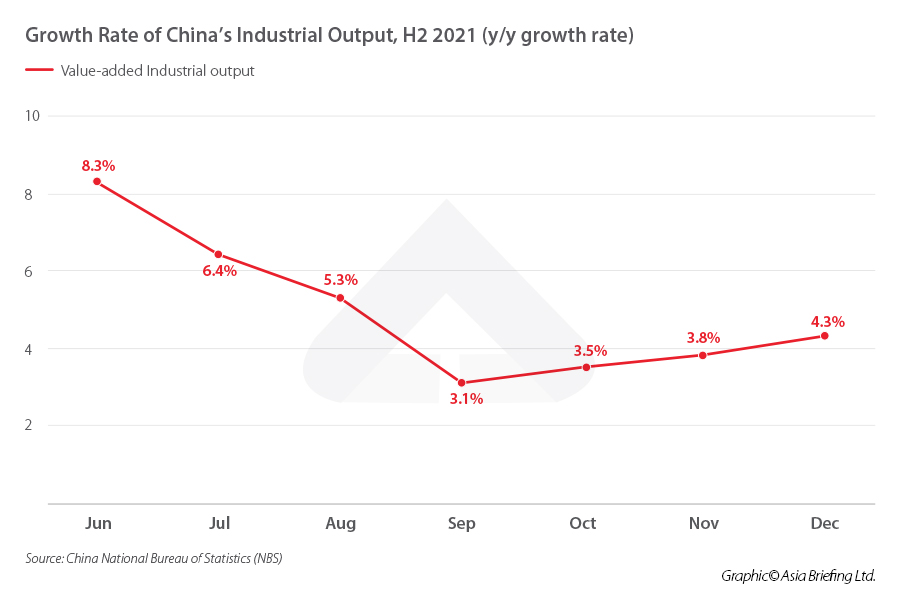

Industrial production was a bright spot in 2021. Value-added industrial output – which measures production by factories, mines, and utilities – went up 9.6 percent for the full 2021 from 2020, with the two-year average growth of 6.1 percent exceeding the pre-pandemic level in 2019.

In December, industrial production rose 4.3 percent year on year, up from the previous month’s 3.8 percent growth rate and beating market expectations ranging from 3.1 to 4.1 percent. This implies that the supply constraints from the power and chip shortage seem manageable.

Notably, China’s automotive production grew for the first time since April, up by 3.4 percent year-on-year in December. Auto sales in 2021 grew for the first time since 2017, boosted partly by a x1.5 jump in sales of new energy vehicles (NEVs).

Consumption slows

China’s total retail sales for consumer goods – including spending by households, governments, and businesses – rose 12.5 percent year on year for 2021. The figure was 16.4 percentage points higher than that of 2020.

In December, the total retail sales grew 1.7 percent from the same period a year earlier, weaker than November’s growth rate of 3.9 percent. The figure largely fell short of economists’ expectations ranging from 3.4 to 4.6 percent, and marked the slowest expansion since August 2020, suggesting a weakening consumption.

Specifically, the catering industry continues to suffer from the impact of the pandemic, with a year-on-year decline of 2.2 percent in December. For the whole 2021, catering industry revenue and retail sales increased by 18.6 percent and 11.8 percent, respectively, with a two-year average growth rate of -0.5 percent and 4.5 percent, both lower than pre-pandemic levels.

While the country’s per capita GDP stood at US$12,551 last year, approaching the World Bank’s threshold for a high-income country, China’s household discretionary income growth grew at a slow pace, slipping to 5.4 percent year-on-year in Q4, down from 6.3 percent in the previous quarter.

What are the options in China’s policy toolkit?

To counter the economic headwinds, it is predicted that the government will roll out more monetary easing and fiscal support measures, shore up liquidity in the property market, integrate domestic and foreign trade, secure the global supply chains, and boost the consumption.

The monetary easing and fiscal support will follow a logic of avoiding large-scale stimulus while lending targeted support to segments that Beijing prioritizes, like small business and high-tech sectors.

In fact, there are already signs of an easing cycle. Over the past few months, the central bank has already started taking multiple targeted monetary easing measures, including:

- Cutting banks’ reserve requirement ratios (RRRs) by two respective 0.5 percentage point in July and December 2021.

- Cutting benchmark mortgage lending rate in January 2022 to juice liquidity in the property market:

- Cutting the five-year loan prime rate (LPR) – which is typically used to price mortgages – from 4.65 percent to 4.6 percent, the first cut since April 2020; and

- Cutting the one-year LPR – which is widely used for other forms of lending – from 3.8 percent to 3.7 percent in January, the second straight month the central bank has cut the rate.

- Cutting its medium-term lending facility (MLF) loans by 10 basis points to 2.85 percent, the first reduction since April 2020.

In December 2021, the State Council also announced a slew of fiscal support measures to specifically support micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) to mitigate against the downward economic pressures. The measures include:

- Extending loan support policies for small and micro-sized enterprises until June 2023.

- Including microcredit loans in the relending support plan for agricultural and small businesses.

- Establishing a national integrated financing credit service platform to provide microfinancing to MSMEs.

- Improving the regulations on performance appraisal and due diligence exemption of microcredit loans issued by financial institutions, supporting financial institutions to issue special financial bonds for MSMEs, and expanding the scale of government financing guarantee business for small and micro enterprises and reducing guarantee costs.

As infrastructure investment was depressed, the government has taken action to speed up issuance of special-purpose bonds (SPBs) – the SPBs are designed fund commercially viable infrastructure and public welfare investment.

In December, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) offered local governments an early allocation of RMB 1.46 trillion (US$230 billion) in quotas for 2022 SPBs – many economists and analysts think the slower issuance of SPBs in 2021 had weakened infrastructure investments of that year, which dragged down economic growth.

As exports show signs of slowdown and external demand is predicted to fall back, the Chinese government is also finding ways to promote market diversification and cross-border e-commerce, help exporters gain more customers at home, and ensure the unimpeded operation of global supply chains.

For example, on January 19 this year, the State Council issued the Opinions to Promote the Integrated Development of Domestic and Foreign Trade, which proposed to promote the “convergence of domestic and foreign rules for trade and mutual recognition of supervision”, improve the “consistency of domestic and international standards”, and encourage companies to “produce domestic and foreign products on the same production line, to the same standard, and at the same quality”.

However, whether the strategy will work out will also hinge on whether domestic spending can rebound amid the lingering COVID-19 outbreaks and China’s hardline lockdowns.

Domestic consumption – a key element of China’s Dual Circulation Strategy (DCS) – will weigh more heavily on policymakers’ minds this year. The government may place more emphasis on sustaining the economic and household income growth and further push its common prosperity campaign.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article Can Employers in China Unilaterally Request Employees to Use Paid Leaves during the Period of COVID-19 Prevention and Control?

- Next Article China’s Corporate Credit Risk Classification System – What We Know