The RCEP Trade Deal and Why its Success Matters to China

In its latest round of negotiations held on August 30 and 31 in Singapore, the trade ministers of the parties to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) collectively agreed to push for a conclusion to the mega trade deal by November.

While discussions between RCEP participants began six years ago, 2018 was fixed as the deadline to finalize an agreement.

A major sticking point, however, has been the level of commitment shown by each of the countries involved.

For example, while Japan wants close to full market access, India is unwilling to offer tariff liberalization on all goods and seeks greater market access for its services sector.

This means talks have frequently gotten stuck as some member countries potentially secure greater access than others – in terms of percentage of goods subject to lower tariffs.

Many countries also fear opening up their economy even further to Chinese manufactures, given that China usually dominates its bilateral trade relationships.

On its part, China needs more expansive market access due to its excess manufacturing capacity, trade tensions with the US, and an ongoing economic slowdown.

What is the RCEP and how is it different from the TPP?

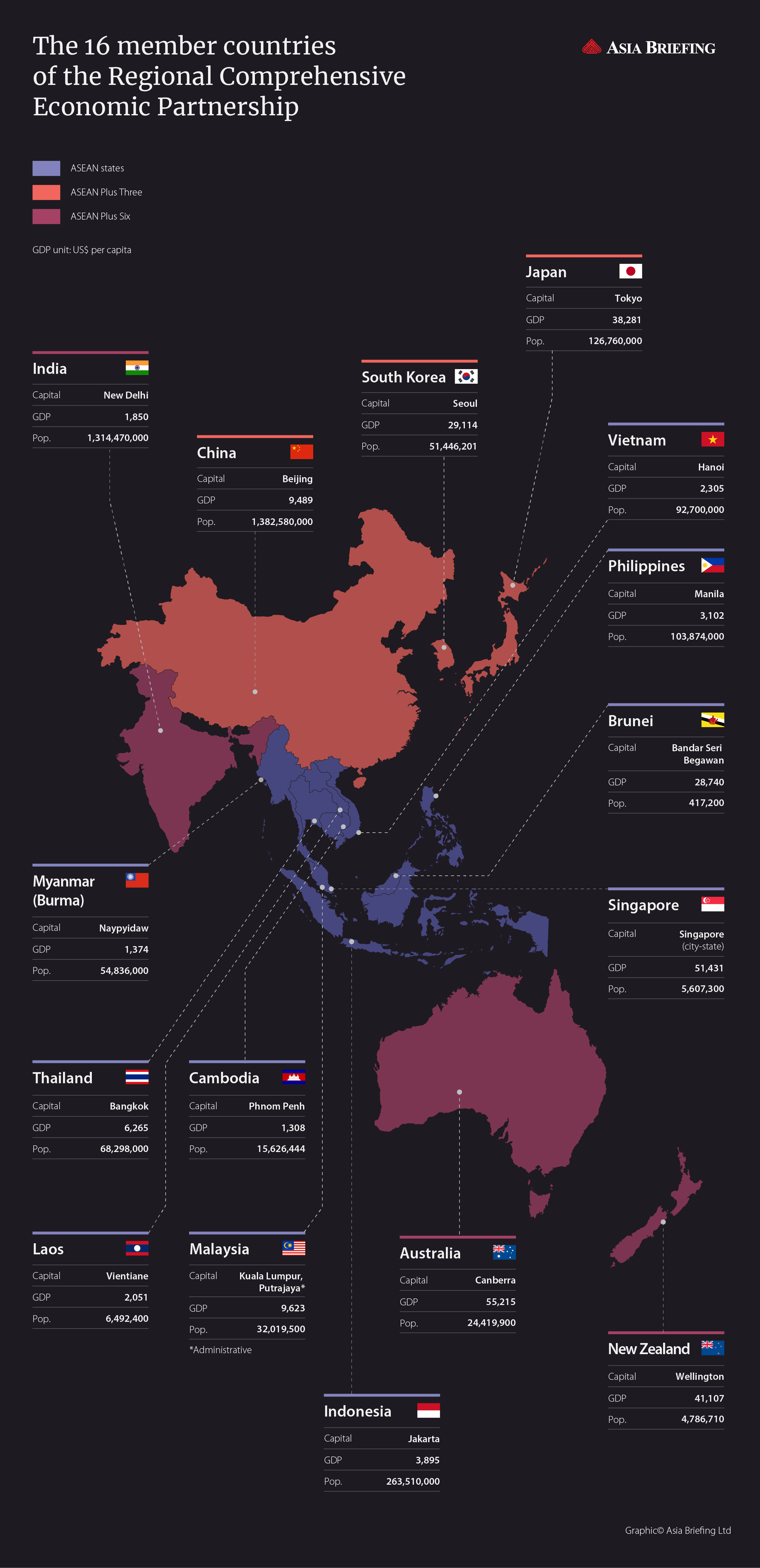

RCEP is a China-backed group that involves the 10 ASEAN members as well as China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and India – the six Asia-Pacific countries with whom the ASEAN has working free trade agreements (FTAs).

RCEP is among the most ambitious trade groupings in the world, accounting for about 45 percent of the world’s population and about a third of its GDP.

Negotiations among RCEP participants began in November 2012, and cover goods, services, investments, economic and technical cooperation, competition, and intellectual property rights.

In the past, the grouping was viewed as an alternative to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which excluded China and India.

Negotiations to the TPP may be traced back to 2008, and was a proposed trade agreement between the US, Canada, Mexico, Chile, and Peru and seven other countries who also took part in RCEP negotiations – Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei. The exclusion of China in particular was considered to be a strategic move by some of the member countries.

While TPP negotiations successfully concluded in February 2016, the US withdrew from it as soon as President Donald Trump took over the White House, in January 2017 – upholding a key election campaign promise.

Currently, the now defunct TPP is sought to be revived as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP11). It will come into effect 60 days after being ratified by 50 percent of the participating states; only Mexico, Japan, and Singapore have ratified the TPP11 as of August 2018.

Both the TPP11 and RCEP seek to lower tariff and non-tariff barriers and open participating economies for investment.

Where the TPP11 differs from RCEP is in its comprehensive coverage of trade in goods and services, opening of investment sectors, e-commerce, the dispute settlement process, intellectual property protections as well as regulating the role of state-owned enterprises.

Takeaways from the RCEP Singapore Ministerial

The two-day Singapore Ministerial concluded on August 31 with the 16 members adopting a package of year-end deliverables.

All RCEP members agreed to give their binding offers on easing the movement of workers by October 10. Member countries also agreed to establish an investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism, albeit for limited sectors.

India, being the most reluctant participant, saw more concessions than earlier expected. It will benefit from a ‘bilateral pairing mechanism’, meaning India will be allowed to separately negotiate with non-FTA partners – China, New Zealand, and Australia. Further, India will be allowed a time-frame of over 20 years to eliminate tariffs on key items from China.

Trade negotiators will now work out the operational details of the final agreement in the next few months, and will meet in Auckland, New Zealand between October 17 and 24. Two more rounds of ministerial consultations are also expected to take place before the heads of states meet for the RCEP Summit in November.

As India, Indonesia, and Australia face major elections in 2019, aspects of the RCEP trade deal might have ramifications on the domestic politics in these countries. These could either block progress on the deal, intensify the end-of-year negotiations, or simply delay a final agreement.

Why the RCEP matters for China

The rapidly escalating trade war between the US and China is disrupting business between the two countries. Given how Chinese manufacturers and their US clients are bound closely by global supply chains, the rising tariffs on Chinese imports is creating losers on both sides.

Meanwhile, Chinese manufacturers are simultaneously facing the pressures of rising factory wages, increase in raw material prices, and trade uncertainties. At this inflexion, a breakthrough in the RCEP trade deal is crucial for China to be able to weather the tit-for-tat tariff wars with the US.

Moreover, since the US backed out of the TPP in early 2017 and the UK chose to exit the EU the year before, China has emerged as the foremost voice calling for trade liberalization and globalization. Improving regional trade ties is also key to improving China’s relations with Japan as well as respective Southeast Asian countries, where geopolitics have often tested bilateral ties.

Given the rise of trade protectionism across the world and its own ongoing economic slowdown, a successful conclusion to RCEP talks will assure China of market access and exchange of technology know-how. Both are key to its national plan to upgrade the country’s manufacturing industry to achieve more value-added production.

Besides, at present, the most vulnerable segment in China are its smaller manufacturers.

While it may appear that their fortunes waver at every Trump tweet and tariff decree, these firms are already battling multiple macroeconomic challenges – rising land and labor costs and industries relocating to cheaper destinations like Vietnam and Indonesia.

The trade war with the US has only aggravated the plight of many of these firms, who are increasingly looking for financial reprieve from state banks, even as China moves to reduce risky lending and reform its funding policies.

For China, securing access to diversified markets under RCEP holds major consequences – it means providing economic certainty to its homegrown businesses, which positively impacts employment growth and internal consumption demand.

Finally, China appears to be on the war path with financial reforms – implementing policies to encourage fiscal responsibility, ease investment norms, cut down tax liabilities, and consolidate compliance standards.

Ensuring the country’s overall macroeconomic stability is therefore an outstanding priority for the Chinese government. A successful conclusion to the RCEP trade deal will support this objective.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia and maintains offices in China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Russia, and Vietnam. Please contact info@dezshira.com or visit our website at www.dezshira.com.

- Previous Article China’s New IIT Law: Prepare for Transition

- Next Article Labor Dispatching and Outsourcing in China: Choosing the Right Strategy