The Putin-Xi Moscow Summit: What Will Be Discussed

Regional security, energy, trade, infrastructure development, new financial payments systems, and Ukraine are all likely to be covered in detail

By Chris Devonshire-Ellis

The Moscow summit between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping begins today (Monday, March 20, 2023) and is expected to last for three days. Following this, there is speculation Xi will hold a videoconference with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to try and find some common ground for peace. Ukraine however will not be the only item on the agenda as Russia and China have much else to discuss in terms of regional security, infrastructure development, energy supplies, trade, and new financial systems technologies. In this article, we discuss these issues.

Regional Security – The Shanghai Cooperation Organization

An issue that has gained increasing priority in Russia-China relations as a consequence of the Ukraine conflict is regional security, and this means strengthening the military and security aspects of the collective Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). The SCO was founded in 2001 and now includes eight member States (China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan), four Observer States interested in acceding to full membership (Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, and Mongolia) and six “Dialogue Partners” (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Turkiye). In 2021, the decision was made to start the accession process of Iran to the SCO as a full member, while Egypt, Qatar, as well as Saudi Arabia, became dialogue partners.

The SCO is in the process of being enhanced beyond this status. Sergey Lavrov, the Russian Foreign Minister, and Zhang Ming, the Secretary General of the SCO have been discussing this past week procedural aspects of Iran and Belarus’ accession to full membership of the organization, as well as the process of formalizing relations with proposed new dialogue partners, being Bahrain, the Maldives, Myanmar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates. If concluded, this will give the SCO regional coverage over the complete Eurasian land mass to the borders of Eastern Europe, as well as include significant gains in the Middle East and South-East Asia. This is likely to be seen as the world ‘beyond the West’ within a new Cold War and has specific ramifications in the energy and trade sectors. It is also likely to become a reality.

The West will point to the SCO as being a ‘threat to NATO’ and as a justification for continuing to arm Europe and for continuing the conflict in Ukraine. Russia and to some extent China view NATO as the initial problem as it has expanded eastwards. The SCO will emerge as the security front line between the two.

Trade – Bilateral and Multilateral Agreements

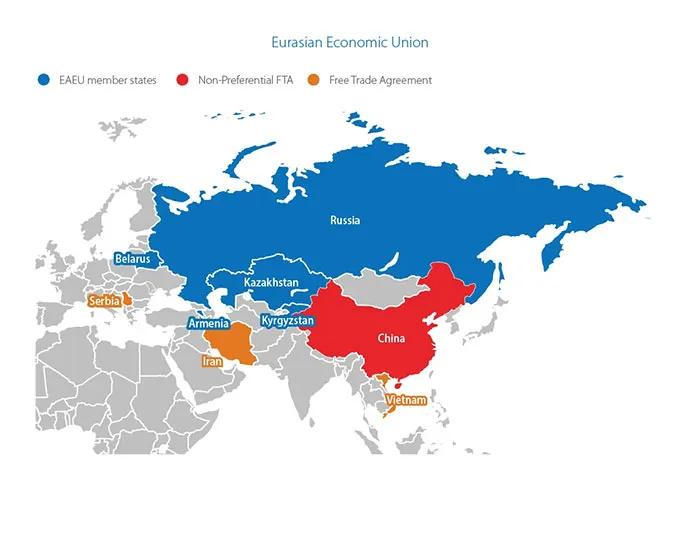

The SCO isn’t just a security bloc however, it also has a significant trade development portfolio. Yet in addition to the SCO, other regional trade blocs are also gathering momentum, most notably the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the BRICS. It can be expected that given a renewed emphasis on the SCO to engage in security affairs, the trade aspect of it may play out within the EAEU and BRICS instead, meaning their roles will also be enhanced.

The Eurasian Economic Union

This can be seen in that the EAEU membership largely mirrors the SCO coverage. At present, the EAEU includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia and fills the northern Eurasian landmass from the borders of Eastern Europe to Western China. It also has free trade agreements, most notably with China (non-preferential) Iran, Serbia, and Vietnam.

However, negotiations are also underway to develop the reach of the EAEU. Numerous other countries have applied for Free Trade Agreements with the bloc, including major economies such as India, Indonesia, Turkiye, and the UAE.

The EAEU has taken on additional significance for Russia since its foreign trade has been increasingly limited by the sanctions of Western developed countries. However, this is partially offset by the EAEU trade. Intra-EAEU trade reached a record high of over US$80 billion last year, while Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan increased their exports to other EAEU members by US$9.8 billion in 2022, a 40% year-on-year increase, of which Russia imported the vast majority at US$9.5 billion worth, good news for the smaller EAEU nations as their exports increased by a significant amount.

Top of the pile though in terms of securing a deal are adding finishing touches to the EAEU-Iran deal, which is already operational but requires some amendments, as well as reaching a free trade agreement with Egypt. The deal with Cairo is expected to be concluded this year and would give the EAEU reach into North Africa – Russia sees Egypt as a gateway into the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) and has built a Free Trade Zone in Port Said, near the Suez Canal.

Also commencing negotiations is Indonesia, which would provide the EAEU with a significant and developing presence in Vietnam.

Then there is the China aspect. Beijing signed an FTA with the EAEU in September 2018, however, it remains ‘non-preferential’, meaning no tariff reductions have been agreed upon by the two sides. I discussed this apparent anomaly with the EEC (The EAEU’s governing body) Trade Minister Andrey Slepnev at the Far Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok in September last year, who explained that the status “allowed flexibility on a government-to-government basis” and that tariffs were reduced on an as need basis from time to time when market conditions suited. That makes sense – China has a huge export manufacturing capacity and manufactures hundreds of thousands of different products – getting a trade deal in place to cater for all of these would take years and face regional political delays in terms of EAEU countries being concerned that some cheaper Chinese products could decimate some of their domestic manufacturers.

But that said, it transpires that the EAEU and China are now discussing changes to the 2018 agreement. The Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP) noted last week that the EEC is also preparing to revise its current agreement with China. The country’s share in EAEU total trade increased by 23% in 2022. Both the EEC and China plan to discuss the depth, ambitions, and industry directions in terms of expanding cooperation between China and the EAEU. To date, the EAEU roadmap with China has three sections: the digitization of transport corridors, dialogues on foreign trade policy issues, and a joint scientific study of various scenarios for deepening cooperation, including trade liberalization. How this plays out remains to be seen but enhancements to the EAEU-China FTA can be considered likely.

BRICS

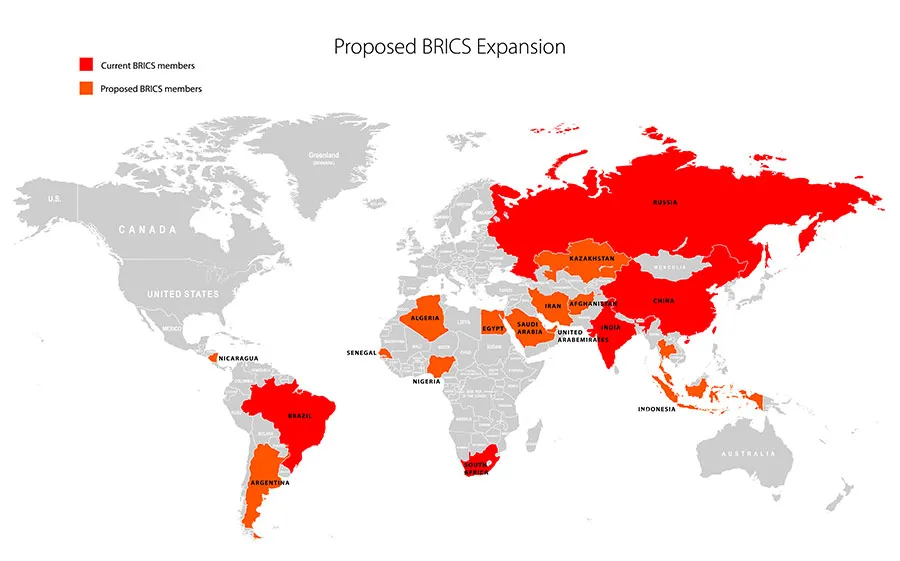

The development of the BRICS group and the expansion to the BRICS+ will also be discussed. Currently, BRICS includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. The obvious difference between this and the EAEU is that the BRICS is pan-continental. Each of its members has been chosen as the lead nation within their own regional trade blocs; we already discussed Russia and the EAEU. Brazil is the primary member of the Mercosur Latin American trade bloc, India the lead of the SAARC and BIMSTEC South Asian blocs, South Africa the southern gateway to the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), and China a lead into the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

At present, the BRICS are a loosely arranged cooperative and do not have their own free trade agreement between them, relying instead on their respective bilateral agreements. But each member does enjoy free or preferential trade within their own respective blocs.

Multiple other countries have expressed official interest in joining the BRICS, which could lead to a significant expansion and introduce a more formal type of trade and development agreement between them.

In total, the BRICS grouping as it currently stands accounts for over 40% of the global population and nearly a quarter of the world’s GDP. The GDP figure is expected to double to 50% of global GDP by 2030. Expanding BRICS will immediately accelerate that process.

The Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has stated that Algeria, Argentina, and Iran had all applied, while it is already known that Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, Egypt, and Afghanistan are interested, along with Indonesia, which made a formal application to join at last year’s G20 summit in Bali.

Other likely contenders for membership include Kazakhstan, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Senegal, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates. All had their Finance Ministers present at the BRICS Expansion dialogue meeting held in May 2022.

While much thought needs to be put into place about how to absorb these countries into a singular trade bloc and the type of structure this would require, the global dimension of the BRICS is of geopolitical interest to observers not least because it suggests the identity of nations not entirely content with being reliant on a Western-lead trade organization. China and Russia can be expected to be taking the lead in BRICS development. An obvious step forward would be to combine elements of this, gradually, with the EAEU.

China-Russia Bilateral Trade

Bilateral trade between the two countries was just shy of US$200 billion in 2022 and is expected to comfortably exceed this in 2023. That means that the 2024 goal of meeting the US$200 billion target, set by both Presidents in 2018 will have been reached a year in advance.

While most commentators on this subject tend to showcase their bilateral trade as an energy play, non-energy trade is also growing. This is partially because numerous Western manufacturers exited the Russian market, leaving Chinese, and other manufacturers to step in. The Chinese auto industry for example has increased its Russian market share by 20% in 5 months. Other manufacturing sectors, such as Western white goods and household appliances have also been replaced by Chinese and other Asian brands.

While Russia’s trade dynamics remain somewhat unpredictable at present, there has not been too much stress on the Russian consumer. Markets remain full and although brands and origins of products may have changed, there have been few, if any long-term shortages. Cheese for example is now sourced from Iran, Argentina, and Morocco. Wines are imported from South America and South Africa. The list of replaced products is lengthy. China of course will want more of this; Russia is one of the few countries with which it has a trade imbalance, mainly due to the huge volumes of gas and oil it imports. But the non-energy bilateral trade sector is growing and can be expected to develop fast and further.

That leads me to believe that Presidents Putin and Xi, having achieved the targeted US$200 billion in bilateral trade, may set another. Steps towards US$300 billion by 2030 would appear achievable. Our recent in-depth analysis of China-Russia trade potential for 2023 can be viewed here and contains some interesting perspectives – such as Russia’s use of China as a goods transit country in order to reach markets in ASEAN.

China-Russia Infrastructure Development

China has several border crossings with Russia and the upgrading and expansion of these will also be on the agenda. China is also a gateway for Russia to access ASEAN and has very well-established supply chain routes to and from ASEAN, and especially via its border connectivity with Vietnam.

China’s trade with Russia is now about at the same level as its bilateral trade with Vietnam at US$234 billion and Malaysia at US$209 billion. China’s trade with ASEAN is growing at a pace comparable with Russia, and reached 11.2% growth in 2022, achieving a total trade balance of US$975 billion.

However, China’s trade with the EU increased by only 2.4% (US$847 billion), and with the United States by 0.6% (US$759 billion). These trends are marked given political pressures upon China from both the EU and the US and are unlikely to change. This means that the Russian and Chinese economies will continue to converge, and not only will Russia’s dependence on China grow, but vice versa.

The ASEAN aspect is also important to Russia as it spreads its pivot to Asia further east and south. It has a successful free trade agreement, via the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) with Vietnam. Russia already supplies Vietnam with energy, and is keen to expand this (the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline will assist) while non-energy trade is also rapidly expanding. Rail connections already head south from China’s border with Kazakhstan to Yunnan and connect with Vietnam’s rail system, which is being developed to provide connectivity to other ASEAN markets.

Vietnam is a developing agricultural play, while Russia and Belarus export fertilizers and agricultural machinery, a point that was discussed at some length between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Belarus President Lukashenko recently. Belarus is also a member of the EAEU and is keen to expand trade east as it too is sanctioned by the EU. Vietnam sells Russian seafood; Russia sells Vietnam pork and beef. That bilateral trade has grown from also zero to US$622 million in five years. Although geographically far apart, their mutual trade efficiencies match while rail infrastructure has made them closer.

Russia’s desire to trade east means that its relationship with China is also expanding into China becoming not just a valuable import and export market, but also a transit nation between Russia and ASEAN. It should be noted that while Singapore has currently suspended negotiations to engage in an FTA with the EAEU, fellow ASEAN members Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand have all officially applied. Russia’s trade with these countries today is relatively small; China’s onboard as a transit route and pending free trade agreements will change that. Increasing infrastructure developments between the two will result, although the funding for this will be between the two and not involve either the Asian Infrastructure Investment or BRICS New Development Banks as both have shied away from providing Russian loans in the wake of sanctions threats. However, with new bridge and railway connectivity between the two countries now coming online, more infrastructure development can be expected.

New Financial Payment Systems

Also on the agenda will be discussions concerning mutual trade and financial settlement systems. The issue is that the US has threatened to disconnect Chinese banks from SWIFT if they connect with Russia’s MIR system or if Beijing connects China’s CIPS financial messaging system with Russia’s SPFS. Both countries regard that as impinging upon their sovereignty (and they are right).

As alternatives, they are looking for a balanced Ruble/ RMB Yuan trade. Russia exports to China more than vice-versa and the Ruble is stable, resulting in a positive environment for developing this further. Both countries are actively looking at decreasing their use of the US dollar, with Russia well ahead of China in this regard, both in terms of policy and as a result of sanctions. That has meant the Chinese RMB Yuan is now a currency of choice in bilateral trade as it has convertibility. It also means that the Ruble-RMB Yuan trade will increase.

In time, such trade will be digital and involve national cryptocurrencies. However, there are regulatory issues with these. Crypto usage is currently speculative but on sovereign terms, they will end up tightly regulated and act as replacements for existing currency. But both China, with the Digital Yuan, and Russia with the Digital Ruble are trialing these. Such use will bypass the SWIFT banking network and render bilateral trade via the US dollar partially obsolete, although as a global currency, it will continue to be used in China’s trade with the West.

Another alternative is arriving, the development of an asset-backed currency, such as a gold ‘stablecoin‘ that Russia is working towards with Iran: a system that the West has kept quiet about as it really could be a global financing and settlement game-changer.

Elvira Nabiullina, the head of the Central Bank of Russia is expected to visit Iran shortly to discuss the efficiencies of payments in their respective national currencies, with a plan to define and agree on the timeline and conditions for both countries to launch a gold stablecoin. The concept has been in the works for a while now, and both countries’ central banks have jointly dedicated specialists in a working group for developing such a stablecoin and have been actively working together both in Teheran and Moscow.

This effort is being prioritized as efficient trade has long been hampered concerning settlements between Russian and Iranian companies. It has been estimated that the two countries can increase their volume of trade to US$10 billion or more per year by using a payment system alternative to SWIFT, specifically by using digital financial assets (DFA), which can be secured by gold.

A Russia-Iran stablecoin may pave the way for other types of stablecoins to be introduced. As Russia is resource-rich, such tokens could be backed by other commodities, such as diamonds, oil, gas, and even fresh water and timber. China will be extremely interested to see how this pans out. It can also be expected to usher in changes in the way the world settles its trade and other payments internationally – – the current situation is driving these innovations ahead.

Ukraine

China released a ‘12 Point Peace Plan’ a couple of weeks ago, welcomed by Russia and stated to be ‘of interest’ to Kiev. On the other hand, it has been rejected out of hand by the collective West. US media, close to the White House called it ‘A Trojan Horse’ EU political institutions stated it was ‘Actually about Taiwan’. Other Western reactions were equally dismissive.

The danger here is that the rest of the world has a vested interest in this conflict too, essential supply chains have been disrupted in both food and energy and have created real stress factors in multiple developing nations. Increasingly, Western rhetoric about the Ukraine conflict is seen as shrill, increasingly prone to conspiracy theories and misinformation, and warmongering in itself. This is especially true as all Western nations have already dismissed any proposed Chinese attempts to negotiate a cease-fire and any negotiations with Russia as ill-advised at best and dangerously ‘pro-Russian’ at worst. The non-Western world increasingly sees this as a desire to continue the conflict – instigated by the West.

But China has interests in Ukraine too, and vice-versa. Ukraine is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative and has received loans from China to re-develop and expand Ukrainian ports, roads, and rail infrastructure. China is also Ukraine’s largest trade partner providing 14.4 percent of its imports and as a destination for 15.3 percent of its exports.

Pre-conflict, Chinese companies also saw opportunities in Ukraine’s energy sector, including renewables (solar and wind) and nuclear power. Ukraine hopes to become self-sufficient in uranium and there have been discussions with the China Development Bank about Chinese investment in this sector. China imports nearly all of the uranium it uses.

In June 2021 Ukraine and China signed an intergovernmental agreement to promote joint cooperation in infrastructure development, while the country is estimated to have borrowed as much as US$1 billion – 12% of the country’s total budget deficit in 2020 – from China to finance road construction projects.

Beijing will be looking to assist with Ukrainian reconstruction in the event the conflict can be resolved and will likely be offering Kiev loans to do so. If so, this may be conditional on Chinese construction companies carrying out the work given outstanding loans and construction MoUs being in place – meaning Ukraine has a cheaper option than EU contractors to rebuild, and China’s loans are effectively returned to the country in payments for infrastructure and other reconstruction build.

That will suit Zelenskyy, who will be looking to counter expensive EU reconstruction costs with those from a competitor. With only Romania from the EU being a trade partner of any note, (Ukraine’s second largest trade partner is Turkiye), the trade and reconstruction angle that could be offered by Xi is likely to be considered by Zelenskyy whether Washington or Brussels likes it or not. The difficulty the West has is that in being seen to deny an opportunity for peace in Ukraine – the onus of responsibility for the continuation of the war falls increasingly upon them.

Xi’s visit to meet Putin and any subsequent intervention in the Ukraine situation, and the reaction to this is therefore of immense global importance with implications for all.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates. He may be reached at chris@dezshira.com

Related Reading

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article Breakdown and Analysis of China’s Economic Data for January and February 2023

- Next Article China Resumes Accepting Applications for Commercial Performances

RUSSIA’S PIVOT TO ASIA – How Russia and China Have Anticipated A New Cold War, The Impact On Western Sanctions Effectiveness And The Global Implications

RUSSIA’S PIVOT TO ASIA – How Russia and China Have Anticipated A New Cold War, The Impact On Western Sanctions Effectiveness And The Global Implications