Holding up Half the Sky? Assessing the Current State of Female Employment in China

By Zolzaya Erdenebileg

Female employment in China used to be moving in a positive direction. In the late 1970s, almost ten years after Chairman Mao famously remarked that “women hold up half the sky”, about 90 percent of working-age women in cities were participating in the workforce. In 1980, China was one of the first countries to ratify the United Nations International Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW). In 1992 and 1994, gender equality was integrated into Chinese law, with the Law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women and the Law on Maternal and Infant Health Care being signed into practice, respectively.

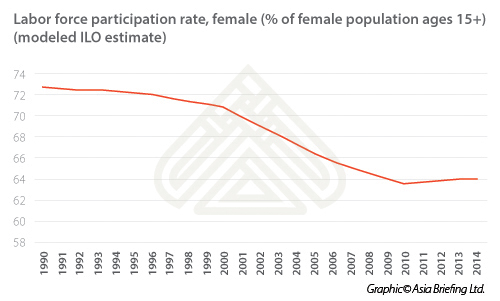

But recent statistics now show that the composition of the workforce is becoming increasingly unbalanced. The trend is clear – female employment rates in China are steadily decreasing. According to data from the International Labor Organization (ILO), the work participation rate of women dropped nine percentage points from 73 percent in 1990 to 64 percent in 2014.

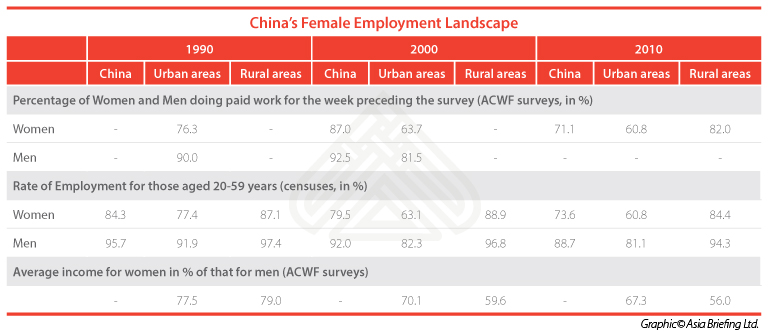

According to the 2010 national census, the rate of employment for women between the ages of 20 and 59 in 1990 was 84.3 percent. In 2000, it had dropped to 79.5 percent, and in 2010, it was 73.6 percent. Statistics from the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), a state-sponsored women’s rights organization, are about the same or lower – it put the participation rate at 71.1 percent for 2010.

Nevertheless, China’s female employment participation rate is on-par with, and sometimes better than, many developed countries. In 2014, Canada’s female employment participation rate was 61.4 percent; Norway was 61.2 percent; Sweden was 60.2 percent; and the U.S. was 56 percent.

The drop is partly explained by China’s economic transformation over the last two decades. As the country has moved away from labor-intensive employment towards consumer goods and services employment, women’s participation in the workforce has decreased in tandem. However, China’s shift to a service and consumption driven economy does not explain all aspects of the country’s falling female employment rate. For a fuller picture, government policies and social pressures have to be taken into account.

![]() RELATED: Payroll and HR Services from Dezan Shira & Associate

RELATED: Payroll and HR Services from Dezan Shira & Associate

Urban vs. Rural Female Employment

However, an important distinction has to be made at this point. China’s overall employment rate includes statistics for women in urban and in rural areas. This is significant for two reasons. Firstly, despite rapid industrialization during the past three decades, China is still heavily dependent on the agricultural sector, which employs roughly equal numbers of men and women, with some years more female-dominated than others. Secondly, China’s future is highly urban. It is projected that close to 70 percent of China’s population will live in cities by 2030.

Therefore, rates for urban women are seen as the best indicators to track gender equality within the workplace, and those numbers are much lower, as seen in the table below:

In 2010, according to census data, the employment rate for urban women aged between 20 and 59 was 60.8 percent. This is a full 16.6 percentage points lower than in 1990, when it was 77.4 percent. On the other hand, rural women employment decreased only 2.7 percentage points, despite heavy industrialization between 1990 and 2010.

Resurgence of Traditional Gender Norms

The ebbing of female workers in China comes at a time of a gradual resurgence of traditional gender norms that places the majority of household and childrearing responsibilities on women. The popularity of the perception that the public domain is for men, and the domestic domain is for women (男外女内) has increased 7.7 percentage points amongst men and 4.4 percentage points amongst women since 2000. There has been a concerted effort to encourage women to focus on marriage and family instead of careers, most prominently through the dissemination of the “leftover women” (剩女) term. “Leftover women” refer to those past the ripe old age of 27 with high levels of education and successful careers, but who have yet to marry. While some believe that the term is complimentary, it was initially a derogatory term used to galvanize well-educated women to marry and procreate.

Besides public perception, female-friendly policies have also eroded. Systems in place to aid working mothers, such as subsidized healthcare, largely disappeared after the economic reforms of the 1990s. While 72 percent of mothers between the ages of 25 and 34 with children under the age of six are employed, economic reforms in the 1990s have reduced the number of options available to working mothers. In particular, government support for subsidized childcare has significantly decreased. According to the 2006 Chinese enterprise social responsibility survey, less than 20 percent of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and 5.7 percent of all enterprises included provided childcare for employees.

Women who have not yet had children are also discriminated against during the hiring process. In China, maternity leave is paid and must be a minimum of 98 days. For some employers, this is a disincentive to hire women. The ACWF survey found that 72 percent of women believed that they were not hired or passed over for promotion because of their sex; 75 percent believed that they were fired because they either were married or became pregnant.

Another limitation within the workplace is mandatory retirement ages. For women in blue-collar positions, the required retirement age is 50. For women in white-collar positions, the age is 55. For some women hired in special positions, like college professorships, the retirement age matches those of urban men, which is 60. Again, some employers choose to use this policy to justify discriminatory hiring practices.

In addition, there is a prevalent gender pay gap within China. On average, women earn 35 percent less than men for similar work. This places China near the bottom of the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) 2015 Global Gender Gap Index, ranking 91st out of 145. In urban areas, women’s average annual income is equivalent to 67.3 percent of men’s income; in rural areas, it is only 56 percent.

Lacking Representation

The issue may continue to proliferate because women are severely underrepresented in leadership roles in China. The WEF report found that, while women outpaced men in educational attainment, political empowerment numbers were very low. In 2015, the female-to-male ratio for enrollment in tertiary education (beyond high school) was 1.15. However, the ratio for positions in parliament was 0.31; for ministerial positions, it was 0.13; and for years with head of state positions within the last 50 years, it was 0.08. No woman has ever been a member of the nine-member Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party, the leaders of China’s government.

In the corporate world, the situation is more encouraging, but still has ample room for growth. According to the Asia Development Bank (ADB) Women’s Leadership and Corporate Performance, women made up four percent of company chairs, and 5.6 percent of CEOs.

![]() RELATED: China’s Work-related Insurance Scheme

RELATED: China’s Work-related Insurance Scheme

Looking Ahead

Despite the inauspicious state of female employment in China, more and more women are getting higher degrees to increase their competitiveness. Already, women outnumber men in Chinese higher education. In 2013, 50.7 percent of students enrolled in tertiary education were women. In 2014, China had the highest number of Graduate Management Admissions Tests (GMATs) taken by female citizens. 37,631 Chinese women took the exam, or 65 percent of total Chinese test takers that year.

Given uncommon but well-publicized rulings, policies may evolve as well. On December 18, 2013, China settled its first gender discrimination lawsuit in Beijing. In the case, a women named Cao Ju filed suit against the Juren School, a private training institute, for rejecting her job application on the basis of her sex. While she settled for RMB 30,000, the case drew wide attention to the issue of discrimination against women in the workplace, raising hopes that vague policy wording will be backed up by tangible consequences.

|

Asia Briefing Ltd. is a subsidiary of Dezan Shira & Associates. Dezan Shira is a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in China, Hong Kong, India, Vietnam, Singapore and the rest of ASEAN. For further information, please email china@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com. Stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends in Asia by subscribing to our complimentary update service featuring news, commentary and regulatory insight. |

Human Resources and Payroll in China 2015

Human Resources and Payroll in China 2015

This edition of Human Resources and Payroll in China, updated for 2015, provides a firm understanding of China’s laws and regulations related to human resources and payroll management – essential information for foreign investors looking to establish or already running a foreign-invested entity in China, local managers, and HR professionals needing to explain complex points of China’s labor policies.

How IT is Changing Payroll Processing and HR Admin in China

How IT is Changing Payroll Processing and HR Admin in China

In this edition of China Briefing magazine, we examine how foreign multinationals can take better advantage of IT in the gathering, storing, and analyzing of HR information in China. We look at how IT can help foreign companies navigate China’s nuanced payroll processing regulations, explain how software platforms are becoming essential for HR, and finally answer questions on the efficacy of outsourcing payroll and HR in China.

Labor Dispute Management in China

Labor Dispute Management in China

In this issue of China Briefing, we discuss how best to manage HR disputes in China. We begin by highlighting how China’s labor arbitration process – and its legal system in general – widely differs from the West, and then detail the labor disputes that foreign entities are likely to encounter when restructuring their China business. We conclude with a special feature from Business Advisory Manager Allan Xu, who explains the risks and procedures for terminating senior management in China.

- Previous Article e-Commerce in Asia – New Publication from Dezan Shira & Associates

- Next Article Human Resources and Payroll in China 2016/17 – New Publication from China Briefing